Downhill/Uphill: A Mountain and an Academical Village–Part 2

Authors Nancy Takahashi and Garth Anderson discuss in detail the University of Virginia‘s historical dependency on resources from “Parcel 1B,” a lesser-known tract of land in the Academical Village. Ms. Takahashi is a Distinguished Lecturer and Director of UVA’s Graduate Landscape Architecture Program in the School of Architecture. Mr. Anderson is the Facilities Historian in UVA’s Geospatial Engineering Services, Facilities Management.

Authors Nancy Takahashi and Garth Anderson discuss in detail the University of Virginia‘s historical dependency on resources from “Parcel 1B,” a lesser-known tract of land in the Academical Village. Ms. Takahashi is a Distinguished Lecturer and Director of UVA’s Graduate Landscape Architecture Program in the School of Architecture. Mr. Anderson is the Facilities Historian in UVA’s Geospatial Engineering Services, Facilities Management.

The following excerpt is Part 2 (of 2) of the article “Downhill/Uphill: Material Flows Between a Mountain and an Academical Village” by N. Takahashi and G. Anderson. Landscript 5: Material Culture Assembling and Disassembling Landscapes. (2017) Berlin: Jovis Verlag.

You can read Part 1 of this article. Listen to the Lifetime Learning podcast “Thomas Jefferson’s Plan for Mount Jefferson to Sustain his Academical Village” featuring Nancy Takahashi.

Part 2 (continued from Part 1)

Flowing Downhill: Wood and Stone

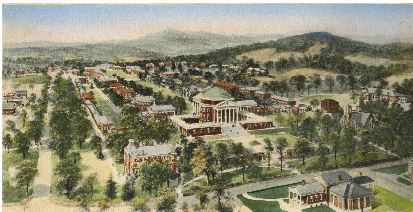

A well-known 1906 lithograph suggests the University’s early dependency on the resources of Parcel 1B. From a birds-eye view, the mountain rises in the upper right corner in the distance. The artist depicts the top of the mountain as wooded, but the lower east and north slopes below are denuded, evidence that the chestnut oak forests had been largely cleared by this time. Wood would likely have been in heavy demand to fuel the University’s kitchens, domestic fireplaces, and the brick kilns of the time. The Proctor’s records suggest that enslaved laborers and independent contractors cut wood.

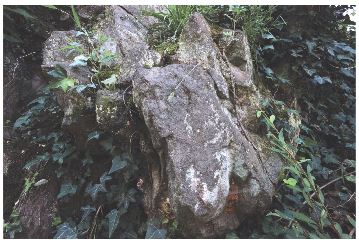

Rock quarries found on Parcel 1B speak to another material dependency on the mountain. The first stone extracted on Parcel 1B came from a small quarry sited at the eastern base of the mountain next to the headwaters of Meadow Creek. While the Rockfish Conglomerate proved unsuitable for architectural components like column capitals and bases, it was used extensively in the original structures for steps and sills, and building walls in the landscape.

Flowing Downhill: Piped Water

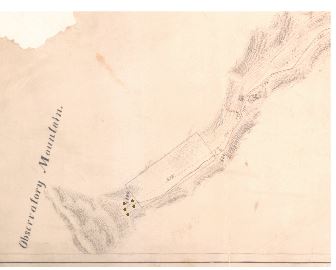

Builders of the new University thoroughly surveyed the water emanating from Parcel 1B. A first system was immediately constructed to transport water through hollowed wood logs from a reservoir vessel on the mountain. From the beginning, however, sourcing potable water proved problematic. In 1856, the University commissioned the design services of the prominent civil engineer Charles Ellet to deal with its chronic water problems. Ellet’s plan called for replacing the original, failing wood pipes with cast iron pipe laid from the mountain spring to the base of the Rotunda. Ellet’s proposal included an in-ground, excavated reservoir whose greater size would retain water during surplus periods and release it during periods of scarcity. At that time, the engineering of upland reservoirs was a new and controversial concept, raising concerns about the stagnation of open bodies of water. For over a century, the reservoir was maintained and was a popular leisure destination, but in 2007 the dam was breached to meet new regulations for safety and monitoring.

In 1888, the building of a larger off-site reservoir effectively terminated the University’s dependency on Parcel 1B as the source of its water. However, Parcel 1B’s role in providing water would continue. The University leased a 3.5-acre site on the upper eastern slope of Parcel 1B to the city, where they built and operated a new water treatment facility. When it opened in 1923, the Observatory Water Treatment Plant, with its state-of-the-art system of sand filtering beds and open-air water storage basins, began providing safe water for the University and the city. Over the decades, the mountain plant has seen expansions and upgrades, and today treats approximately 450 million gallons of water annually to service the University population of roughly 36,000.

Flowing Uphill: Uranium-235 and Noise

Facing an arms race with Nazi Germany during the Second World War, UVA joined the ranks of classified military research institutions comprising the top-secret Manhattan Project. Led by renowned physicist and UVA Professor Jesse Beams, a distinguished research team of chemists and physicists assembled on the grounds of UVA to develop a high-speed centrifuge for uranium isotope separation to power the first nuclear bombs. Operating in the shrouded seclusion of the basement of Rouss Hall—one of the McKim, Mead, and White buildings constructed just south of the Academical Village—the secretive and dangerous nature of Beam’s lab required that the buildings be patrolled by armed guards around the clock and surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. However, the high level of noise, vibration, secrecy, and dangers of wartime engineering proved incompatible with campus life and by 1946 plans were underway to relocate a new Ordnance Research Laboratory (ORL) away from the campus center to Parcel 1B.

Flowing Uphill: More Uranium

With the end of the Second World War, nuclear engineering could turn its attention from a military focus to the promise of atomic power to effect positive change—to heat American homes, light its cities, perhaps even cure cancer. In 1958, under the urging of the Dean of Engineering, UVA joined seventy-five universities across the country and created its own nuclear engineering program, producing hundreds of nuclear scientists up until 1998.

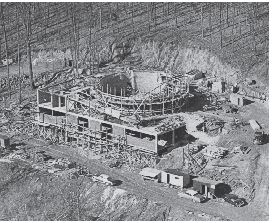

To house the program, a state-of-the-art, one-megawatt nuclear reactor was erected on Parcel 1B in June 1960. Central to the facility was its swimming pool reactor—a 70,000-gallon water reservoir into which samples were lowered for irradiation. The pool’s massive seven-foot-thick concrete walls shielded researchers from harmful radiation emitted by ten to twenty aluminum fuel “plates” containing “bomb-grade” or 93 percent enriched 235-isotope uranium. With the precedent of Beam’s Ordnance Research Lab on Parcel 1B, the mountain became the site for a second science facility utilizing uranium. The decision was made to place the reactor facility near ORL and directly on the north bank of the University’s original water reservoir from the eighteen-sixties. Nestled into the slope, the bedrock was seen as a protective barrier against potential radiation.

It is ironic that the reactor facility was built next to the body of water that was constructed to safeguard clean water one hundred years earlier. The site plan for the reactor annotates the former reservoir as a “Waste Pond.”

Flowing Uphill: Trash

A decision by the university’s BoV in the early twentieth century sealed Parcel 1B’s fate as the de facto destination for the institution’s trash. In the early decades of the new institution, garbage and human waste were disposed of in drains and small dumping sites on the outskirts of the Academical Village. As the university community expanded and trash volume grew, a centralized dumping and burning area was established on the southern terminus of the Lawn below Cabell Hall. In 1922, residents in the increasingly gentrifying neighborhood to the south —apparently suffering from the noxious smoke—made a “prayerful” petition to the BoV to relocate the “injurious” dump. The BoV conceded and relocated the dump to the eastern base of Parcel 1B. The chosen site was along the banks of the mountain creek in the quarry that had been the original source of stone for the Academical Village.

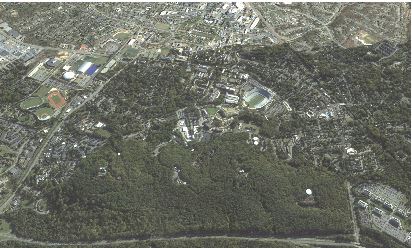

In time, this relocated dump along Meadow Creek would expand into what is now the base of operations for the university’s Facilities Management, which oversees the maintenance of the UVA buildings and grounds. The University’s increasing volume of waste would continue to move uphill, now to a landfill built in the 1930s on the south slope of Parcel 1B. In time, this landfill would expand to cover over five acres, replacing the 1922 dump. The landfill was the university’s dumping site for large-scale rubbish and building demolition rubble until the 1980s, when more stringent EPA regulations took effect. The landfill remains in use today as a staging area where fallen trees and leaf matter collected on campus are piled and composted for use on the UVA grounds. It is yet another ironic reversal of material flow; Jefferson’s Mountain, once the source of timber flowing downhill to build and sustain the University, is now the repository for tree debris and leaf litter carried uphill.

Another signal of Parcel 1B’s status as the University’s waste repository was the decision in 1985 to place the Special Materials Handling Facility and Environmental Health and Safety Building on the mountain. While such a facility reflects new and positive protocols for the safe handling of toxic and chemical waste produced in research labs and facilities, a questionable decision was made to locate this facility on top of Meadow Creek, whose waters were diverted into a twenty-four-inch diameter pipe running around the building perimeter. Similar to the siting of the dumps, landfills, and the Nuclear Reactor Facility, the siting of this facility marked yet another ironic chapter in the life of the Academical Village, which founder Jefferson had proclaimed a century earlier to be, “furnished with good water, and nothing in its vicinity could threaten the health of the students.”

Flowing Uphill Re-evaluated: Carbon

In 2009, UVA’s BoV adopted a resolution to reduce the institution’s greenhouse gas emissions to 25 percent below 2009 levels by the year 2025. Along with energy reduction programs and plans to move from carbon-based to renewable energy sources, UVA has sought to improve the institution’s carbon budget through carbon sequestration in its unbuilt and forested land holdings. Calculating that an acre of woodland sequesters 3.3 metric tons of carbon per year, the mountain—with its still near entirely intact hardwood forest cover—gets a new valuation as a zero-cost contributor to carbon reduction. The mountain forest also hits other important environmental targets in sustainability planning regarding recharging, purifying, and reducing the impact of upstream water.

The BoV’s sustainability actions also harken back to Jefferson’s original idea of instructing through the landscape by calling for the creation of new teaching goals “using our Grounds as a living lab for sustainability.” Several departments already use the mountain for hands-on experiential instruction, including Professor Hank Shugart of Environmental Sciences. In conjunction with the Office of the University Architect, he has worked with students in his Forest Management courses to record the vegetation of roughly 120 thirty-meter plots covering roughly 10 percent of the forest. Shugart researches the future potential of forests and believes that denser, healthier forests can be engineered to match pre-colonial forest conditions through a program of selective plant removals that reduce root and light competition and strategic replanting to increase biodiversity.

Once the neglectful consumer, the modern university institution finds itself increasingly assuming the role of mountain protector, reliant on Parcel 1B for its educational, resource, and ecological benefits.

- Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

- From “Jimmy Who?” to “What Would Jimmy Do?”

- Washington’s Bold Gamble: Christmas Day 1776

- Increasing Your Impact With Planned Giving

- UVA Club of Boston: UVA Men's Basketball Game Watches

- UVA Club of New Mexico: Cavs Care - Roadrunner Food Bank