From “Jimmy Who?” to “What Would Jimmy Do?”

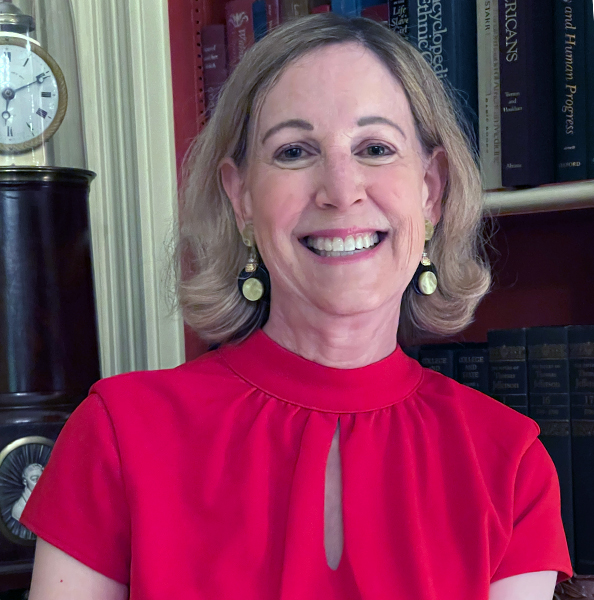

Barbara A. Perry is J. Wilson Newman Professor of Governance and Co-Chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. She serves on the boards of the White House Historical Association, the Supreme Court Historical Society, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Foundation, and the Friends of the John F. Kennedy National Historic Site. Perry has spoken twice at the Carter Center in Atlanta, on First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and presidential mother Rose Kennedy.

Barbara A. Perry is J. Wilson Newman Professor of Governance and Co-Chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. She serves on the boards of the White House Historical Association, the Supreme Court Historical Society, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Foundation, and the Friends of the John F. Kennedy National Historic Site. Perry has spoken twice at the Carter Center in Atlanta, on First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and presidential mother Rose Kennedy.

In what now seems like an innocent verbal misstep, Jimmy Carter famously confessed in a 1976 Playboy magazine interview, “I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times.” I must admit to having a soft spot in my heart for the 39th president. The 1976 election marked my first presidential vote, and I stayed up most of the night to follow the returns until Carter was declared the winner over President Gerald Ford just before 4 a.m.

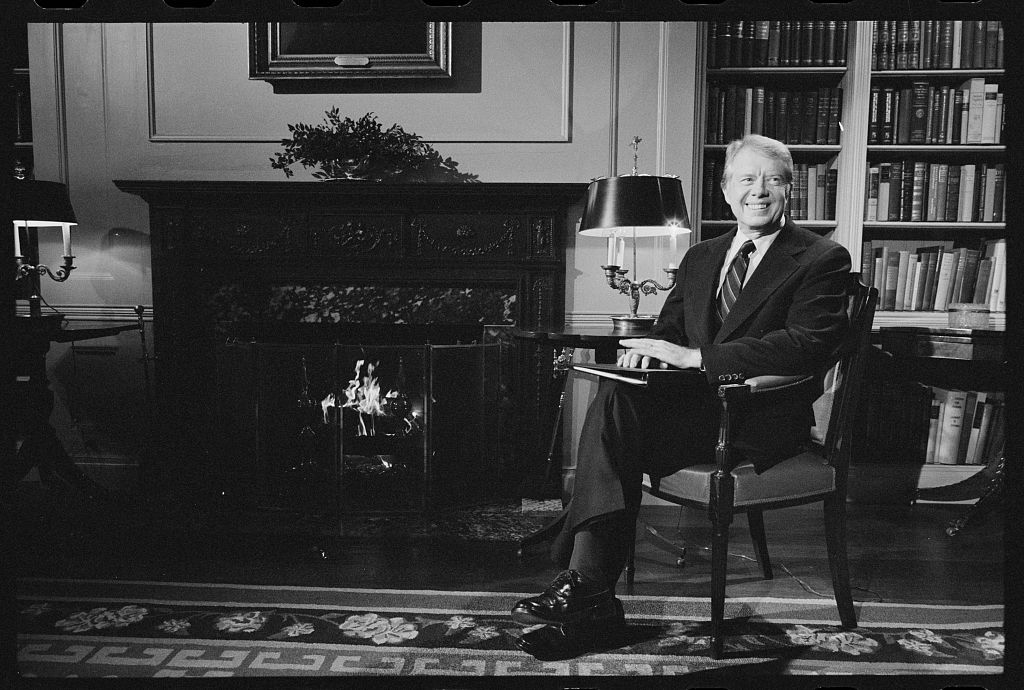

1977, Bernard Gotfryd, Library of Congress

Attending a presidential inauguration was on my bucket list, so I braved the frigid Washington temperatures to witness Carter’s swearing-in and see him and the new first lady stroll down Pennsylvania Avenue. Our long national nightmare of Nixon’s Watergate was truly over. Carter, from the tiny hamlet of Plains, Georgia, was a man of the people. He even carried his own luggage during the primary season.

While the rest of the country asked, “Jimmy who?” as he ran for the Democratic nomination, I had already experienced the little-known former Georgia governor’s prodigious talents at a Democratic Party “issues convention” in 1975. Even on a foreign policy panel, Carter more than held his own with nationally recognized statesmen such as Senator Henry Jackson (D-Wash.) and Ambassador Sargent Shriver.

Carter’s keen intellect, progressive southern populism, integrity, transparency, and faith-based morality combined to produce a tonic for the Watergate-weary nation. “I will never lie to you,” he promised. And he rarely did. Yet the very traits that catapulted this Annapolis-trained nuclear Navy officer and peanut-farmer-turned-politician into the White House contributed to his unsuccessful presidency and 1980 landslide loss to Ronald Reagan.

Carter’s outsider status and lack of Washington experience produced unmanageable headwinds for the president. As he acknowledged in his 1982 oral history interview with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, “[I]n Washington … the lobbyists and the law firms and the news media leaders, in particular the columnists and others, were such an important element of government. And I underestimated that. I don’t think there’s any doubt about it.”

His failure to woo those stakeholders and the American people resulted in a “What Not To Do List” for future chief executives:

- Don’t micromanage. Reviewing requests to use the White House tennis courts (as James Fallows claimed Carter did) does not rise to the level of presidential responsibility.

- Don’t muddle your message. Wide-ranging Q&A sessions with the news media only indicate that the president’s priorities are unclear.

- Don’t focus on the negatives. Members of Congress complained that Carter’s actions to mitigate the energy crisis by reducing speed limits, lowering thermostats, and limiting Christmas lights made it seem that the country was on the brink of disaster.

- Don’t appear weak. From the Iranian hostage rescue fiasco to nearly collapsing while jogging to fighting off an aggressive rabbit (!), the images of Carter’s presidency conveyed failure. One editorial cartoonist drew him as the Mad Hatter of Alice in Wonderland fame.

- Don’t minimize presidential pomp. Trading suit coats for cardigans and eschewing “Hail to the Chief” only diminished Carter’s stature.

- Don’t neglect your party’s base. Putting off the Democratic Party’s more liberal wing, led by Senator Edward Kennedy, proved fatal, especially after Kennedy’s unsuccessful but damaging challenge to Carter’s renomination in 1980.

the Panama Canal Treaty, Washington, D.C., 1978, M. S. Trikosko,

Library of Congress

Carter was simply no match for Reagan, who avoided such pitfalls. In his post-presidency, however, Carter remained true to his humanitarian principles and fashioned a model of global public service that his successors strive to emulate. The perfect candidate, in contrast to Nixon’s Watergate treachery, became an imperfect president presiding over an economic downturn and the rise of Islamic radicalism. But he reemerged as an admired citizen of the post-Cold War world, monitoring elections in new democracies, eradicating diseases in developing countries, and building new homes for the underprivileged around the globe.

Carter’s ledger in history will reflect a presidential leadership deficit but a surplus of dignity and honesty for which his country owes him a debt of gratitude. On questions of personal morality and public service, we should all ask: What would Jimmy do?

====

Footnote: Explore more about Jimmy Carter's life, presidency, and lasting legacy with links to related content from the article.

-

Watch the 1976 election night and read about Carter's modest life in Georgia.

-

Learn about Senator Henry Jackson and Ambassador Sargent Shriver.

-

Delve into the 1980 election and Carter's thoughts on his time in office.

-

Read about the American Enterprise exhibition, failed hostage rescue mission, 62-mile race, and infamous rabbit attack.

-

Examine Carter’s reflections on his unique approach to the presidency.

-

See how Carter's commitment to public service continued through his involvement with the Carter Work Project and The Carter Center. His post-presidential work has impacted global health and democracy.

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Virginia Club of New York x The Essay Conqueror: The College Essayscape

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication

- UVA Club of Washington DC: Hoos in Their Homes