Season’s Greetings, on Postage Stamps

Holiday postage stamps not only deliver greeting cards, but carry a history in the separation of church and state debate, according to Richard Handler, professor in the Department of Anthropology in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and director of the Global Development Studies Program at the University of Virginia. Mr. Handler studies nationalisms in Canada and Quebec, and is currently working on a book with American Studies scholar Laura Goldblatt on the depiction of U.S. nationhood on postage stamps and cancellations. A recent product of their collaboration is their essay, “Toward a New National Iconography: Native Americans on United States Postage Stamps, 1847-1922,” published in 2017 in Winterthur Portfolio.

Holiday postage stamps not only deliver greeting cards, but carry a history in the separation of church and state debate, according to Richard Handler, professor in the Department of Anthropology in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and director of the Global Development Studies Program at the University of Virginia. Mr. Handler studies nationalisms in Canada and Quebec, and is currently working on a book with American Studies scholar Laura Goldblatt on the depiction of U.S. nationhood on postage stamps and cancellations. A recent product of their collaboration is their essay, “Toward a New National Iconography: Native Americans on United States Postage Stamps, 1847-1922,” published in 2017 in Winterthur Portfolio.

Since the United States issued its first postage stamp in 1847, our stamps have by and large observed the idea that church and state should be separate: the vast majority of the more than 5,000 stamps that have been issued to move ordinary mail from 1847 to today have stuck to secular topics.

This changed in the Cold War period when the great opposition between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. was often discussed as an opposition between a society that believed in God and one that didn’t. This is the era in U.S. history when the words “under God” were added to the Pledge of Allegiance and people debated both the place of prayer in public schools and the rights of atheists to have their views respected.

And it was in this context that the first U.S. Christmas stamp was issued, on Nov. 1, 1962. Christmas stamps have been issued annually ever since.

And it was in this context that the first U.S. Christmas stamp was issued, on Nov. 1, 1962. Christmas stamps have been issued annually ever since.

The first three years’ issues posed, but at the same time avoided, the question of whether Christmas stamps make a religious or a secular statement. They stuck to secular symbols of the holiday—trees, greens, and plants—but the very act of recognizing Christmas while not honoring other holidays can be seen as a statement about the Christian foundations of the nation.

In 1965, the Christmas issue depicted an angel, which is a religious symbol. Yet, what is depicted is taken from a watercolor painting of a piece of folk art, a New England weather vane. Thus while the state depicted a religious theme, it did so at one remove, perhaps allowing it to claim (if challenged) that it was depicting not religion but an aspect of national culture, its art.

Depicting Christmas at one remove, in works of art, became the tradition, except the art depicted, after that first angel, was not folk art but high art: paintings of the Madonna and child, which have been issued continuously since 1966.

Depicting Christmas at one remove, in works of art, became the tradition, except the art depicted, after that first angel, was not folk art but high art: paintings of the Madonna and child, which have been issued continuously since 1966.

In 1971, the religious-secular question was built more explicitly into the stamp program, which from that year to the present saw the simultaneous issuing of both a religious stamp and a secular stamp, featuring Santa Clauses, Christmas trees, and scenes of people shopping, wrapping presents and so on.

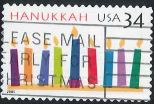

In 1982, we got the first U.S. “love” issue, a stamp for Valentine’s day, which became the second holiday to be postally recognized. Gradually, other religious-ethnic traditions were awarded stamps honoring their religious or seasonal holidays: Chinese New Year (1992), Hanukah (1996), Kwanzaa (1997), and Eid (2001). If the earlier Christmas issues tried to finesse the problem of separation of church and state by pairing religious and secular imagery, these newer holiday stamps do so in a different way, by making Christmas just one among several holidays that our multicultural nation celebrates.

A final word concerns postmarks, which sometimes take the form of what are called slogan cancels, or cancellations in the form of words. One such slogan cancel, in continuous use since 1920, asks postal patrons to “mail early for Christmas.” Here again we have the church-state problem. On the one hand, this injunction can be explained in purely secular terms, as a recipe for making the mail more efficient. On the other hand, that efficiency is required in the service of a religious holiday.

And a final irony: since stamps and slogan cancels come together randomly (when you put a stamp on a letter, you have no idea how it will be cancelled), we get such artifacts as this:

- How to Win a Presidential Debate (or At Least Not Lose One)

- One Researcher’s Community-Based Research in Partnership with Members of an Indigenous Nation

- Not another reading list

- UVA Club of Washington DC: Kickoff to College

- UVA Club of Washington DC: How to Handle Disappointing Grades

- UVA Club of Baltimore: Monthly Virtual UVA Committee Meetings