J-Term: Slavery as a Sociotechnical System

Students in Kathryn Neeley's January Term, or J-Term, course studied historical narratives about slavery to understand its evolution, legacy effects, and relevance today. Neeley is an associate professor in the Science, Technology & Society Program in the School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Virginia.

Students in Kathryn Neeley's January Term, or J-Term, course studied historical narratives about slavery to understand its evolution, legacy effects, and relevance today. Neeley is an associate professor in the Science, Technology & Society Program in the School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Virginia.

J-TERM: SLAVERY AS A SOCIOTECHNICAL SYSTEM

Its Evolution, Legacy Effects, and Relevance Today

During the 2021 January Term, 29 engineering students and I embarked on a hazardous and enlightening intellectual journey: tracing the history of race-based slavery from its beginnings with the Portuguese rediscovery of Africa in 1442 to its twenty-first-century legacy effects. Within this very broad scope, we focused on the construction of historical narratives about slavery as an ethically motivated activity and on slavery as a sociotechnical system.

Understanding our past as a way of defining a positive vision for the future. The ethical dimensions of historical narratives are particularly evident in treatments of slavery, including those that deal with Thomas Jefferson. To make the constructed nature and interpretive functions of historical narratives visible, we constructed narratives using the relatively unprocessed historical record provided by Peter Bergman’s Chronological History of the Negro in America (1969). We also compared histories of slavery and biographical treatments of Jefferson, focusing on the ways that they reflected the ethical concerns of the times in which they were written, a perspective captured in the phrase “We see Jefferson not as he was, but as we are.”

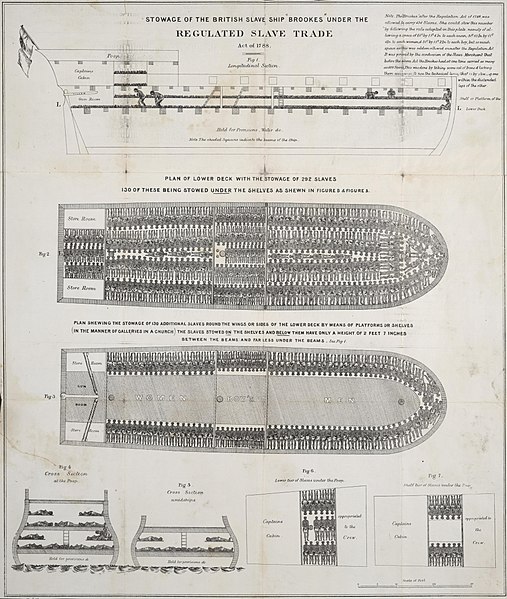

Sociotechnical systems thinking as a path to understanding complex relationships and unexpected outcomes. Sociotechnical systems thinking is central to the field of science, technology, and society (STS). From a sociotechnical perspective, technology is much more than “tools” or other artifacts. We view it instead as goal-oriented human activity that integrates three interrelated elements: (1) technical (material objects, natural processes, and the understanding of how those things work), (2) organizational (individuals, institutions, and activities such as education, regulation, and funding), and (3) cultural (ideals, values, assumptions, and expectations). This approach highlights the moral horror of slavery: treating human beings as though they were tools or machines brought in to develop the abundant natural resources of the New World. What began as an entrepreneurial enterprise solidified into a robust sociotechnical system based on racialized belief systems and institutionalized practices (like segregation in its many forms) that persisted long after the Emancipation Proclamation.

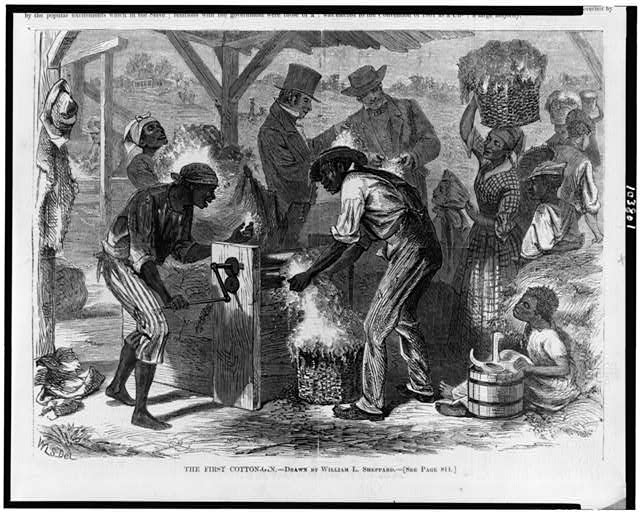

Research as a foundation for raising ethical awareness. Over the course of two weeks, we discovered information that was surprising and distressing but also useful for understanding racial tensions today and for illuminating the social and ethical dimensions of contemporary technology. The cotton gin, that quintessentially American invention, prolonged slavery by making cotton production more profitable. In the south, 7% of White people owned 75% of the enslaved people. Blacks and Native Americans owned slaves. Centuries of exploitation through practices such as robbing the graves of enslaved people to obtain cadavers and conducting involuntary experimentation to facilitate advancements in gynecology and other fields laid the foundation for mistrust in the healthcare system on the part of people of color. Maximizing the volume of human “cargo” that ships could carry spurred innovation in ship design during the Age of Exploration (early 15th century to early 18th century). Facing these facts in all their ugliness is a way to honor and recognize the humanity of the estimated 15 million human beings who survived the voyage from Africa to the New World. Understanding that slavery persisted despite widespread recognition of its fatal flaws can help us see why we should avoid creating and, if possible, reform sociotechnical systems that generate wealth as an intended consequence (Amazon and Facebook, for example) but also have destructive unintended consequences.

As part of our discussions, we speculated on what would have been the best time to reform or abolish race-based slavery in America. The most frequent answer was the Constitutional convention of 1787. Perhaps the most convincing answer was this: at the beginning. Among other things, I hope that my students’ understanding of the origins, evolution, and legacy effects of slavery will expand their moral imaginations as they contemplate the creation of new sociotechnical systems.

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- UVA Northern Virginia Programs Fair

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication

- UVA Club of Richmond: UVA vs VCU Baseball Pre-Game Gathering