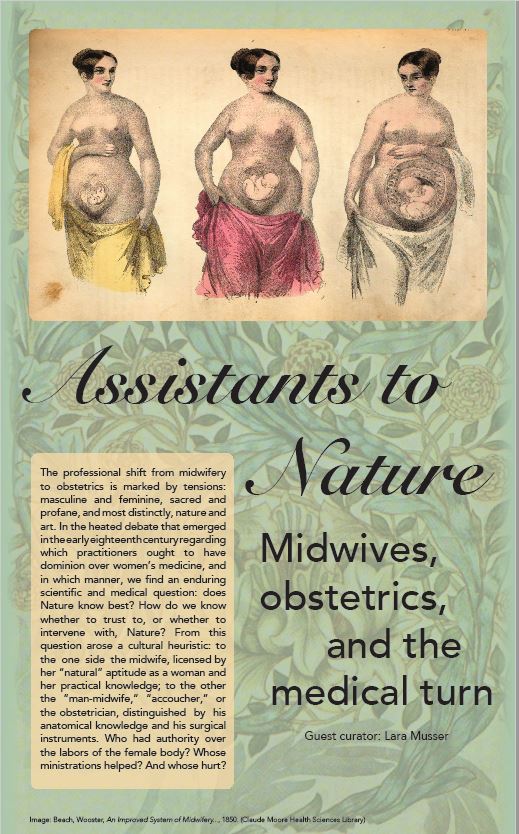

Assistants to Nature: Midwives, Obstetrics, and the Medical Turn

From the 18th through 20th centuries, the birthing process saw a shift from the hands of female midwives to the instruments of male obstetricians. Lara Musser describes this shift in “Assistants to Nature: Midwives, Obstetrics, and the Medical Turn,” a current exhibit in UVA’s Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. Ms. Musser is a lecturer in the Department of English in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia where she teaches courses on science, medicine, and Victorian literature. Her doctoral work focused on 19th-century public science writing.

From the 18th through 20th centuries, the birthing process saw a shift from the hands of female midwives to the instruments of male obstetricians. Lara Musser describes this shift in “Assistants to Nature: Midwives, Obstetrics, and the Medical Turn,” a current exhibit in UVA’s Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. Ms. Musser is a lecturer in the Department of English in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia where she teaches courses on science, medicine, and Victorian literature. Her doctoral work focused on 19th-century public science writing.

My great-grandmother trained as a midwife at the University of Padova. Her alma mater may ring some bells for amateur historians. Padova is a bright star in the history of medicine, the home institution of Galileo Galilei and the anatomical innovator Andreas Vesalius. But also my bisnonna, who delivered infants in her small town in the rocky north of Italy. So I had an inkling of where to turn when Dan Cavanaugh and Emily Bowden let me design an exhibit as part of my work at the Claude Moore Health Science Library’s Historical Collections during the final year of my PhD.

All library exhibits aim to do two things: showcase a collection and tell a story. Modestly sequestered in the lower floors (alright, the basement) of the library, Historical Collections boasts an impressive archive of materials related to the art and act of birth, some sitting comfortably on rolling compact shelves, others cooling in a vault to preserve their centuries-old pages. As I found in my weeks of initial meandering research, this archive paints a fascinating, complex, and sometimes (to modern sensibilities) shocking picture of the long memory of my great-grandmother’s ancient profession. I’d be willing to assert that no event is quite so commonplace and so perilous in the life of every person as their birth. Yet because it is so fundamentally quotidian, the mechanisms and the dangers, to say nothing of the history, of this unique medical event often go overlooked or overshadowed, even for those who are going through it.

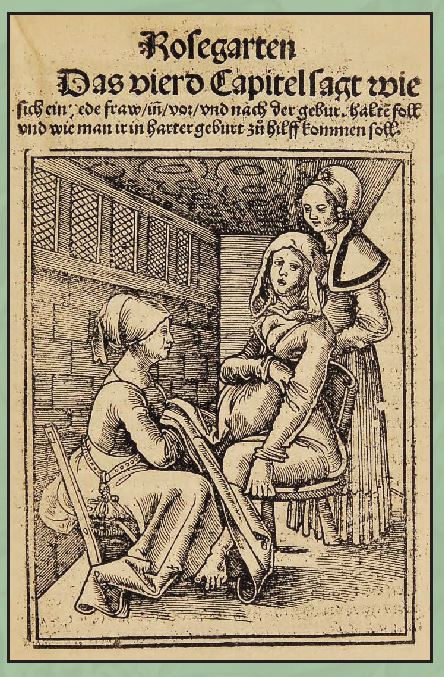

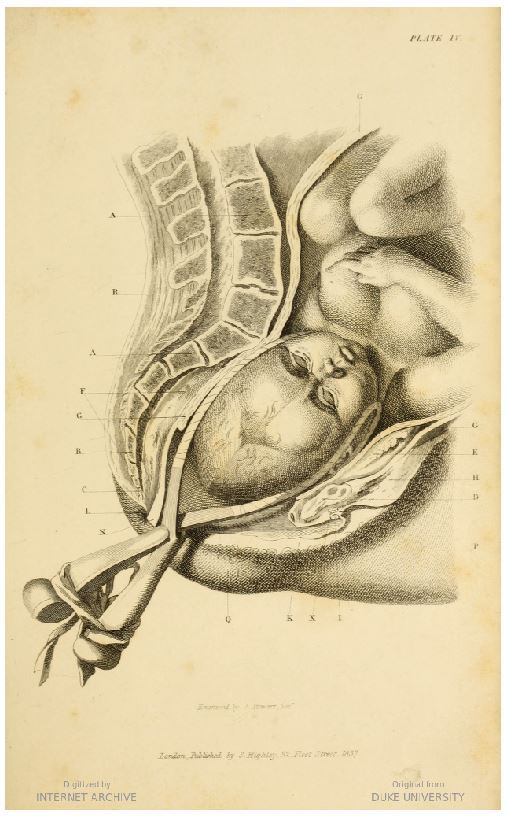

In “Assistants to Nature: Midwives, Obstetricians, and the Medical Turn,” I tried to defamiliarize the familiar and tell in broad strokes the story that the collections at Claude Moore tell about the birth of Western obstetrics and its relationship to its mother practice, midwifery. Midwifery is still a vital profession around the world, including at UVA’s own Midwifery clinic, in which midwives provide hands-on wellness care before, during, and after birth to low-risk pregnancies. But before the 1700s the province of women’s health was theirs alone. Barred from the masculine calling of medicine and surgery, and deprived of formal knowledge of anatomy, women trained each other through a system of informal apprenticeship based on the shared experience of their female bodies. Their tools were mainly their hands, their herbs, and their experience. If birth was a natural—if highly dangerous—event, midwives were framed as “assistants to nature,” ushering infants into the world, burying the dead, stimulating milk, stemming bleeding, and presiding over a domain from which men were, by culture and biology, exempt.

So what happened in the 18th century? Among other things, the forceps. Though they look far less scary than a lot of medical instruments I’ve handled in the library basement, the introduction of the forceps to obstetric practice was part of a constellation of cultural shifts that introduced surgeons (sometimes called “accouchers” or “man-midwives”) for the first time into the domain of female medicine. There’s a lot to unpack in this history: culture, power, race, and gender clash as surgeon-accouchers slowly, and then rapidly, took institutional authority over the one medical event they could never personally experience. Birth became far safer as forceps assisted in births that would have formerly resulted in the death of the infant, mother, or both. Reliable anesthetics and aseptic surgery would follow, making procedures like the Caesarian section a lifesaving option for both mother and child instead of a sober hail Mary performed on a dying woman.

But particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries, these surgical developments, and the fact that more and more Western births took place in the hospital instead of home, meant birth became less of a communal and more of an institutional event. To me, this seemed a critical piece of the story, one that throws into relief our modern “normal.” A place historically avoided as a hotbed of disease became a place to deliver life. A physiological condition once so shrouded in taboo that women had to be “churched” (religiously cleansed) before they could reenter relations with men became superintended almost exclusively by male doctors. In the history of medicine, nothing about standard modern Western birth is “normal” at all.

The story of obstetrics is complicated, frequently flattened into a binary by its own retrospect: out with the old, in with the new. The reality is far subtler. In “Assistants to Nature,” some obstetrical facts and practices even from the past century will seem primitive to modern eyes; but visitors will also find that the more some things change, the more others stay the same. The ubiquitous speculum had basically achieved its final form by Roman times. Our collection’s manual glass breast pump from the turn of the century has an identical twin in a compendium of surgical works from 1555.

Students stay the same too, taking illegible and humorous notes. The material I drew from the library’s collection of medical student notebooks sheds a little light on the obstetrical learnings and doings of our own institution, like the following scribbled in 1931 under “Rules of delivery”: Don’t get in a hurry.

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Women's ACC Basketball Tournament - UVA Fan Events

- UVA Northern Virginia Programs Fair

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication