J-Term: Virginia and the Constitution

“I believe that constitutions are shaped by context—by history, tradition, culture, and politics,” explains A.E. Dick Howard, Warner-Booker Distinguished Professor of International Law at the University of Virginia‘s School of Law. Howard’s January Term, or J-Term, course gave students the chance to study constitutionalism “through the lens of a distinctive place.”

“I believe that constitutions are shaped by context—by history, tradition, culture, and politics,” explains A.E. Dick Howard, Warner-Booker Distinguished Professor of International Law at the University of Virginia‘s School of Law. Howard’s January Term, or J-Term, course gave students the chance to study constitutionalism “through the lens of a distinctive place.”

J-TERM: VIRGINIA AND THE CONSTITUTION

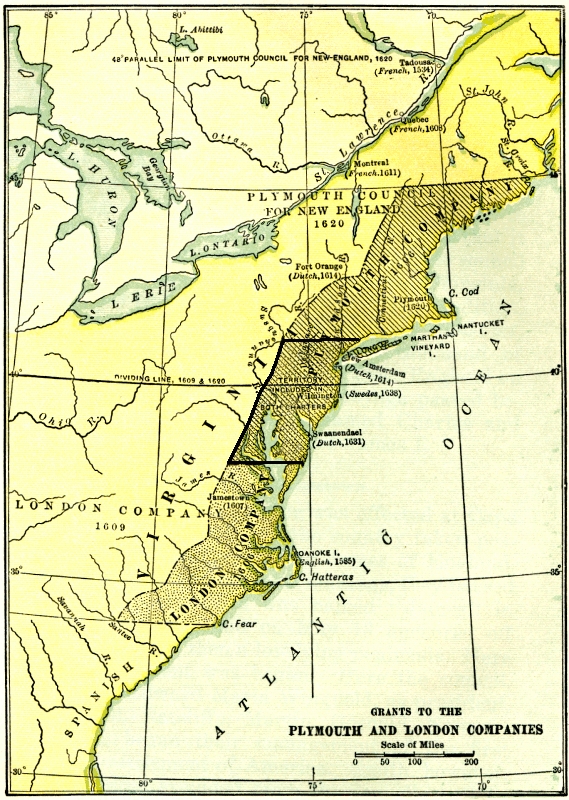

From the beginning of the republic—indeed, long before that—Virginia’s history has been intertwined with the story of American constitutionalism. The Virginia Company Charter of 1606 set the stage for embedding the legacy of English constitutionalism into that of America. Virginia’s Declaration of Rights (1776) was the model for other state bills of rights, presaged the federal Bill of Rights, and even influenced France’s Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789). Virginia’s James Madison has rightly been called the father of the United States Constitution. In the centuries since the founding, many of the great cases in the United States Supreme Court had their origins in Virginia, from the early years of the Republic to our own time.

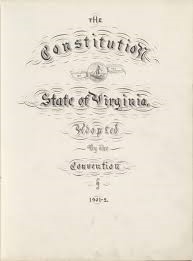

Moreover, the history of Virginia’s own Constitution tells an absorbing tale of its own. Thomas Jefferson famously called on each generation to consider whether the state constitution is adequate to the demands of its era. Virginia’s Constitution has been rewritten several times. Those revisions are a road map to the great social and political debates of successive eras—the Jacksonian era, Civil War and Reconstruction, post-Reconstruction, and, most recently, the current Constitution, which was effective in 1971.

This rich history—some of it occasion for celebration, some of it shameful—led me to offer a J-Term course: “Virginia and the Constitution.” We reflected on seminal documents, personalities, and events, including such landmarks as the 1606 Charter, the 1776 Declaration of Rights, and the Statute for Religious Freedom. We traced the successive revision of the Constitution of Virginia. I asked the students to reflect, in particular, on how Virginia’s Constitution has been used to define the political community: who belongs and who doesn’t, who counts and who doesn’t. The 1776 Constitution dedicated Virginians to pursuing “the common benefit,” but only property owners had the franchise under that document. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the franchise was progressively enlarged until, in 1851, the vote was extended essentially to a universal white male franchise.

The 1870 Constitution, a product of Reconstruction, brought the vote to Black Virginians. But the post-Reconstruction era brought regression in Virginia, as in other southern states. The drafters of the 1902 Constitution set out to enshrine white supremacy through such devices as the poll tax and complicated registration requirements. That changed when, in 1971, a new, progressive constitution sought to chart a more inclusive course for the Commonwealth. Now, fifty years on, in our course we considered changes for our time: making it easier to restore the vote to former felons, seeking to end partisan gerrymandering, and other issues.

In addition to this survey, I asked each student to select, read, and report on one book. They could choose from a list I provided or read a book of their choosing. Some students chose to read biographies. Books on Thomas Jefferson were, not surprisingly, a popular choice. Other books focused on recent events. Two students decided to read President Ryan’s incisive book on two Richmond schools, Five Miles Away, A World Apart.

In previous years, we have ended the course with a field trip to Richmond. There, my friends at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture have kindly given us a close look at prizes from their collection, such as a 1783 draft for a revised Virginia constitution in Jefferson’s handwriting and John Marshall’s copy of The Federalist. We have lingered in the Capitol (designed by Jefferson), where the wonderfully well-informed head guide has regaled us with stories of great constitutional events that took place in the building, including the trial of Aaron Burr and the conventions that drafted several of Virginia’s constitutions.

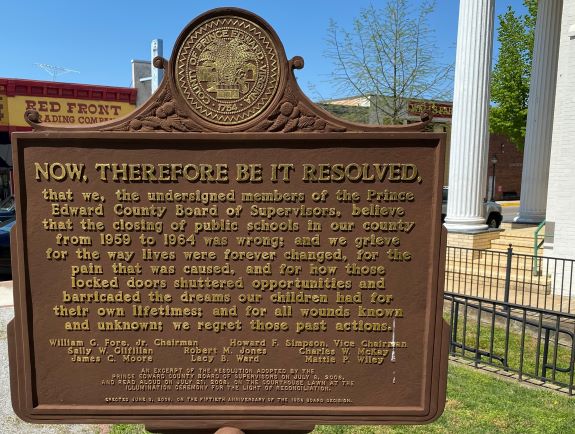

Our J-Term conversation was no exercise in moonlight and magnolias. I sought to use the course to paint a full picture of constitutionalism in Virginia, warts and all. We justly celebrate much of that history; George Mason’s 1776 Declaration stands among the handful of the western world’s many influential documents. Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom was the prelude to the religion clauses of the First Amendment. But there is the darker side. That sobering study reminds us of the 1902 Constitution’s ousting of Black Virginians from the community that counts, of Massive Resistance, of the closing of public schools in Prince Edward County. To reflect on how constitutional ideas have unfolded in Virginia is to be obliged to mull the great issues that shape our lives to this day.

Some of the students who enrolled in the J-Term course were from Virginia; a majority were from other parts of the country. I hope their curiosity about Virginia and its constitutional development spreads to their classmates. I have sat at the elbows of constitution-makers in other countries, especially in post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe. I believe that constitutions are shaped by context—by history, tradition, culture, and politics. Focusing on Virginia—its history, its people, its culture, its politics—gave my students and me a chance to see constitutions and constitutionalism through the lens of a distinctive place.

For more on 2021 J-Term, read:

J-Term: Leadership in Athletics

J-Term: Gender in Sport and Film–Capturing a “Moment of Folly”?

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Livestream: A Conversation with Dr. Cornel West & Dr. Robert P. George

- UVA Club of Knoxville: Cavs Care - KARM Meal Service & Social

- UVA Club of Washington DC: January Book Club