Civil War Generals' Memoirs

Stephen Cushman is Robert C. Taylor Professor in the University of Virginia Department of English. Mr. Cushman has written twelve books, edited five works, and published more than forty articles on topics ranging from poetry to the Bible to the Civil War. He has also received many distinguished teaching awards throughout his career, including the Cavaliers' Distinguished Teaching Professor. On the 162nd year after shots were fired at Fort Sumter, officially starting the Civil War, Mr. Cushman discusses post-war memoirs among Generals of the Civil War.

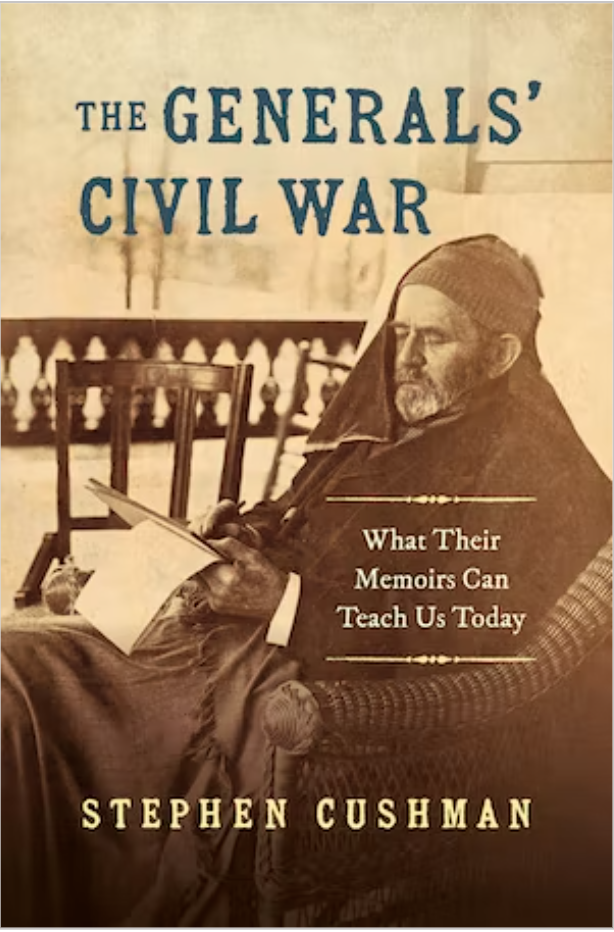

June 27, 1885. Saturday. In a rattan chair on the porch of a borrowed cottage, Ulysses S. Grant sat writing his memoirs. A knitted cap covered his head. A dark shawl veiled the right side of his face. Upstate New York, near Saratoga Springs, could be chilly, even six days into summer. He did not wear the shawl for warmth, though; he wore it to hide a tumor on the right side of his neck and jaw. Swallowing and speaking had become excruciating. Doses of cocaine-water and shots of morphine with brandy helped some but not enough. Sixteen days after he posed for the portrait, he finished his 336,000-word, two-volume work. Nine days later, he died.

The photograph does not show how the former president and General of the Army had been a reluctant writer, turning down all requests from editors until a Wall Street swindle left him penniless. Nor does it show the efforts of his rescuer, Mark Twain, who with keen entrepreneurial instinct, recruited Grant to write the work that would eventually net the general’s widow, Julia, the equivalent today of nearly eleven million dollars.

When Ulysses Grant finished his book, he boosted a memoir bonanza in full swing, one that other generals, from both the loyal states and the seceding ones, had joined as many as twenty years before him. This bonanza reflected the strength of a postwar publishing boom, as the world of print expanded rapidly on many fronts, with the price of paper falling, the literacy rate rising, and periodicals doubling their numbers. As the Civil War faded into the past, many people, few of them professional authors before the war, turned to retrospective writing about their experiences during the national convulsion. But Civil War memory would not have become the force it did, or persist as the force it still is, without the rampaging bullishness of the late-nineteenth-century Civil War memory market.

Driving this market was the strategy adopted by established northern publishers of meeting and creating demand by publishing personal narratives from both sides of the war. They sold their wares in the North and the South, as the number of booksellers in the former Confederacy returned to prewar levels. The politics of Reconstruction might be battleground for others, but for these northern publishers, most of them based in New York, the challenges posed to reconciliation by postwar partisanship among white readers meant good business. In the case of Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, very good business.

The Generals’ Civil War looks not only at Grant’s work but at five other generals’ memoirs published from 1874 to 1888. Two of them, by George B. McClellan and Philip H. Sheridan, Mark Twain also published. Twain’s principal competitor, D. Appleton and Company, published the others, by Joseph E. Johnston, William T. Sherman, and Richard Taylor.

In discussing these memoirs, The Generals’ Civil War also considers their continuing legacy. We take it for granted that leading role-players in recent events will write their memoirs. We would not do so, however, if not for the memoirs of Civil War generals, who were the first Americans to establish a vigorous commercial market for such books.

We also take it for granted that many people, famous or not, have marketable stories to tell and tell them best by using the first-person pronouns I, me, my, and mine. For us, first-person narration makes a story more engaging, accessible, and authentic. Again, we would not feel this way if the personal narratives of Civil War generals had not broken the ground by borrowing first-person techniques popularized by nineteenth-century writers such as Charles Dickens and Mark Twain for nonfiction recollections of historical events.

The Civil War advanced American writing by linking disruptive public events to first-person narratives on a scale never before seen. In doing so, the war revealed something about how public memory was starting to work in the United States, for better or for worse. When it comes to disruptive public events, especially complex ones, many Americans metabolize those events through personal stories. As they became commercial authors, Civil War generals set the table to serve their fellow citizens this new kind of narrative fare.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party