The Cuban Missile Crisis: What Happened and How Close Were We to War?

Fred Borch is a lawyer and historian. He was Professor of Legal History and Leadership for 18 years at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School located at the University of Virginia. He served 25 years in the Army as a uniformed attorney. After retiring from active duty, Fred took a job in the U.S. Government as the only career historian whose focus was exclusively on military legal history. He has seven degrees, including an M.A. in history from the University of Virginia.

Fred Borch is a lawyer and historian. He was Professor of Legal History and Leadership for 18 years at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School located at the University of Virginia. He served 25 years in the Army as a uniformed attorney. After retiring from active duty, Fred took a job in the U.S. Government as the only career historian whose focus was exclusively on military legal history. He has seven degrees, including an M.A. in history from the University of Virginia.

Sixty-two years ago this week, the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 brought the United States close to the brink of nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

- What happened to bring us so near to war with each other?

- How was the conflict averted?

- What lessons were learned by both sides from the event?

Fidel Castro triumphed in Cuba in 1959, and subsequently, his self-proclaimed communist regime looked to the Soviet Union for both economic and military support. After 1,400 Cuban exiles opposed to Castro launched a U.S.-backed but unsuccessful invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, Castro was desperate to prevent any future attack. As a result, he and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev secretly agreed in July 1962 that the Russians would put nuclear missiles in Cuba to deter any future U.S. aggression.

The Cubans and Russians began building missile sites in late summer. On October 14, 1962, an American U-2 spy plane took photographs that showed the construction of sites for ballistic nuclear missiles—missiles that were capable of reaching U.S. soil within minutes after launch.

The Cubans and Russians began building missile sites in late summer. On October 14, 1962, an American U-2 spy plane took photographs that showed the construction of sites for ballistic nuclear missiles—missiles that were capable of reaching U.S. soil within minutes after launch.

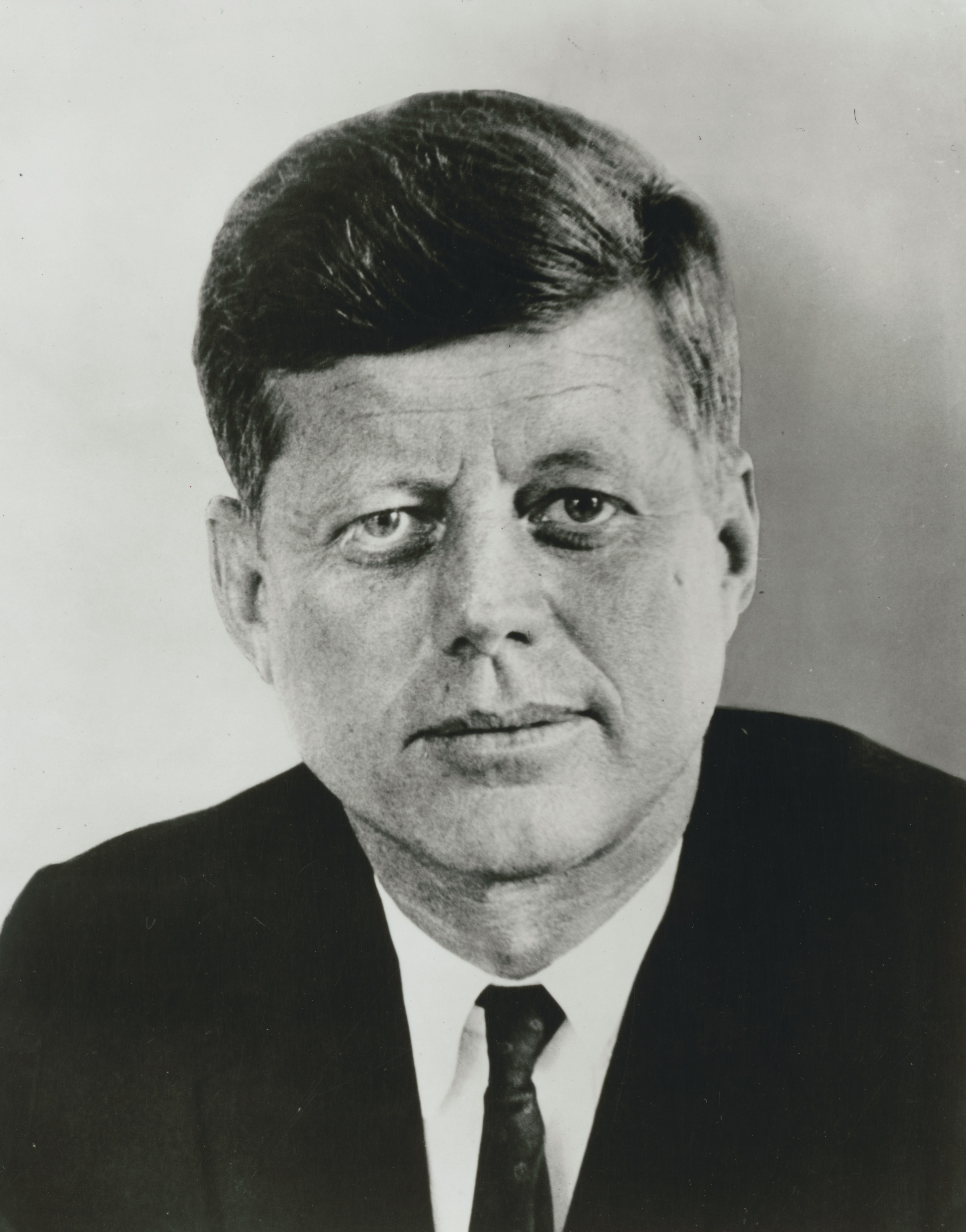

The Cuban Missile Crisis was very close at hand after President Kennedy saw these photos the following day. For the President, these missiles were a “dagger at the heart of the United States,” and he was determined to remove the threat. Kennedy’s military advisors argued for an Air Force attack on the missile sites, followed by a land invasion of Cuba. Others counselled diplomacy. On October 22, Kennedy instead decided to impose a naval “quarantine” of Cuba: U.S. Navy vessels would stop any ships sailing to Cuba that contained offensive weapons.

That same day, Kennedy sent a letter to Khrushchev demanding that the Soviets remove any and all offensive weapons from Cuba. He also insisted that the Russians stop building any missile sites. In the evening, the President appeared on ABC, CBS, and NBC television to tell the American people about the missiles. Kennedy also said that “any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere” would be seen by him as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” To many observers, it seemed that nuclear war between the two superpowers might be likely.

Two days later, on October 24, Khrushchev announced that Soviet ships headed for Cuba would not be thwarted by Kennedy’s blockade. Nevertheless, some ships did turn back from the quarantine line; those that crossed the line were stopped and inspected and, as they had no weapons aboard, were permitted to travel on to Cuba.

On October 26, Kennedy told his advisors that an airstrike on the missile sites appeared to be the only way to resolve the crisis. Concurrently, however, an ABC News correspondent relayed to the White House that a Soviet agent had suggested to him that the Soviets might be willing to remove their missiles if the U.S. agreed not to invade Cuba. That evening, Nikita Khrushchev sent Kennedy a message in which he insisted that the Soviet Union had no interest in triggering “the catastrophe of thermonuclear war” but instead was ready to “take measures” to resolve the crisis. Khrushchev also suggested that the solution was missile removal combined with a pledge not to invade.

On October 26, Kennedy told his advisors that an airstrike on the missile sites appeared to be the only way to resolve the crisis. Concurrently, however, an ABC News correspondent relayed to the White House that a Soviet agent had suggested to him that the Soviets might be willing to remove their missiles if the U.S. agreed not to invade Cuba. That evening, Nikita Khrushchev sent Kennedy a message in which he insisted that the Soviet Union had no interest in triggering “the catastrophe of thermonuclear war” but instead was ready to “take measures” to resolve the crisis. Khrushchev also suggested that the solution was missile removal combined with a pledge not to invade.

Khrushchev then sent Kennedy a second message, writing that any resolution of the crisis required the United States to remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey. About fifteen of these nuclear intermediate ballistic missiles had been in Turkey since the late 1950s and were a symbol of America’s defense commitment to the country.

No sooner had Khrushchev’s second message reached Kennedy than an American U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba. War seemed imminent, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff began preparing for conflict. However, Kennedy decided to try one last time for a diplomatic solution. He ignored Khrushchev’s second message and replied only to the first communication. Kennedy promised that if the Soviets would remove the missiles, there would be no American invasion of Cuba.

In the meantime, the President’s brother, Bobby, met secretly with the Soviet Ambassador to the United States. Bobby told him that the U.S. was planning to remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey anyway but that this information must remain secret and could not be publicized as part of the solution to the crisis.

The next day, Khrushchev announced that Soviet missiles would be withdrawn from Cuba. The Cuban Missile Crisis was over; the U.S. removed its nuclear missiles from Turkey about six months later.

While the U.S. and Soviet Union had stepped back from nuclear war, both sides realized that better communication between the two superpowers was needed. The most immediate result was the creation of the “Hotline”—a direct telephone link between the White House and the Kremlin. Another important lesson from the Cuban Missile Crisis was that both sides realized that more must be done to control the spread of nuclear arms. This resulted in the negotiation of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

While the U.S. and Soviet Union had stepped back from nuclear war, both sides realized that better communication between the two superpowers was needed. The most immediate result was the creation of the “Hotline”—a direct telephone link between the White House and the Kremlin. Another important lesson from the Cuban Missile Crisis was that both sides realized that more must be done to control the spread of nuclear arms. This resulted in the negotiation of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

In retrospect, a military solution to the problem of missiles in Cuba would have been a disaster for both the U.S. and the Soviet Union; it might well have unleashed a nuclear war that neither side could win. Fortunately, President Kennedy refused to accept that there was only a military answer to the crisis; he never stopped looking for a diplomatic solution--and to his credit, neither did Nikita Khrushchev. Ultimately, the Cuban Missile Crisis illustrates that diplomacy can resolve what may seem to demand a military answer. Government officials and politicians who see military force as the answer to world problems today would do well to reflect on the events of October 14-28, 1962.

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: Hoo-liday Party

- UVA Club of Alexandria: TaxSlayer Gator Bowl Game Watch