A Retrospective on the Controversial Use of the Atomic Bomb, 80 Years Later

Fred Borch is a lawyer and historian. He was Professor of Legal History and Leadership for 18 years at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School located at the University of Virginia. He served 25 years in the Army as a uniformed attorney. After retiring from active duty, Fred took a job in the U.S. Government as the only career historian whose focus was exclusively on military legal history. He has seven degrees, including an M.A. in history from the University of Virginia.

Fred Borch is a lawyer and historian. He was Professor of Legal History and Leadership for 18 years at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School located at the University of Virginia. He served 25 years in the Army as a uniformed attorney. After retiring from active duty, Fred took a job in the U.S. Government as the only career historian whose focus was exclusively on military legal history. He has seven degrees, including an M.A. in history from the University of Virginia.

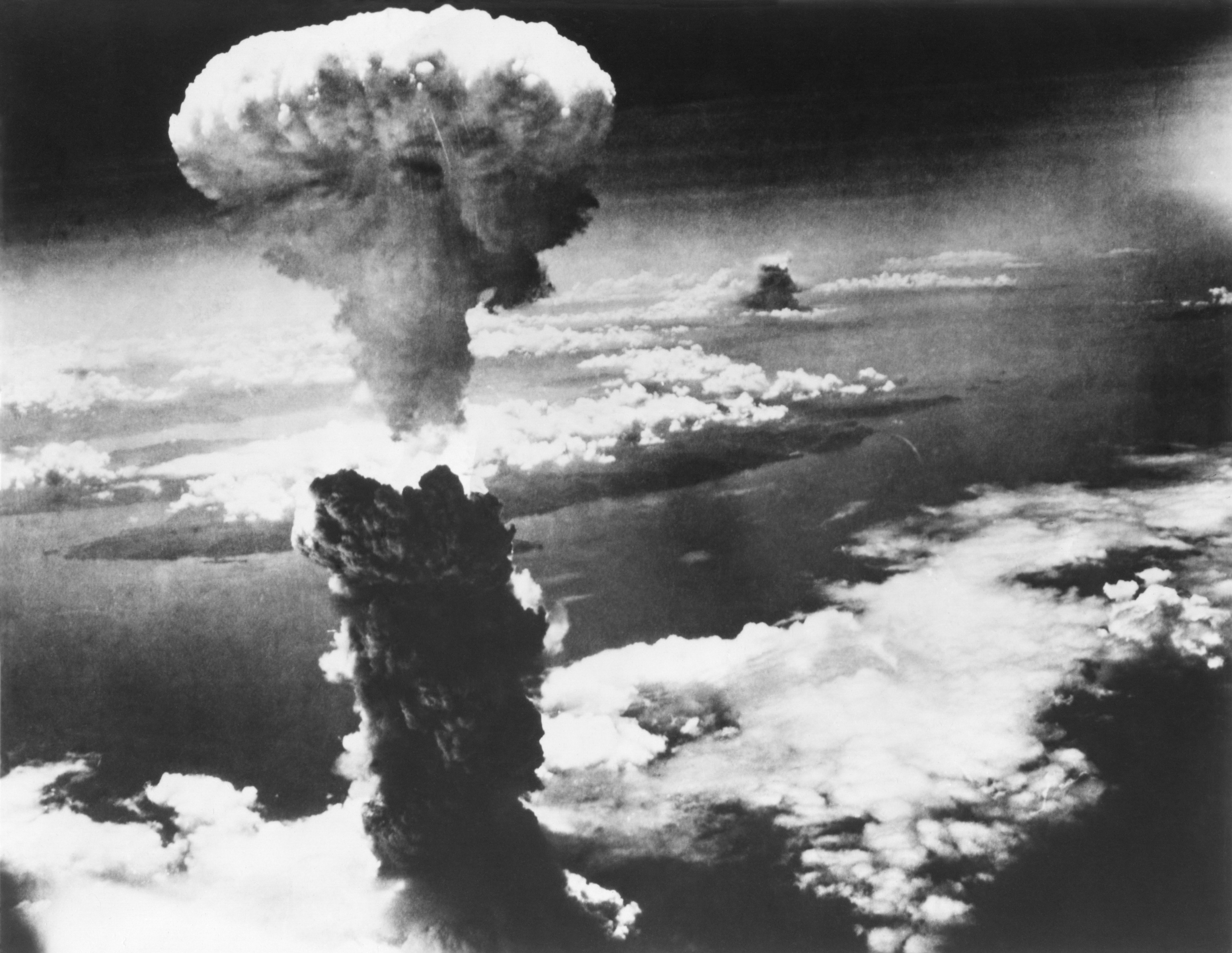

On August 6, 1945, an Army Air Force B-29 dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, a second American bomb fell on Nagasaki. Between 125,000 and 225,000 men, women and children were killed in these two attacks, most of whom were Japanese civilians. While nuclear weapons have never been used again since August 1945, their use 79 years ago remains controversial.

Many historians consider the Manhattan Project, which culminated in the creation of the first fission (atomic) bomb, to be the largest and most complicated technological effort in the history of man. A team of physicists led by Robert Oppenheimer (the subject of last year’s Oscar-winning film) explored the theory and potential applications of atomic fission. Ultimately, at a cost of two billion dollars and with a workforce of 600,000 men and women, the Manhattan Project produced the two atomic bombs that ended World War II.

Even at the time, top scientists were unsure about splitting an atom; some believed that the first atom to be split would ignite a chain reaction that would consume the entire universe. Others thought that an atomic bomb—at least in theory—would have immense destructive power but were unsure about its long-term effects. Nevertheless, the impetus for the Manhattan Project was the fear that the Germans were working to split the atom and create a fission bomb—and if successful, would have a clear path to victory over the Allies.

Even at the time, top scientists were unsure about splitting an atom; some believed that the first atom to be split would ignite a chain reaction that would consume the entire universe. Others thought that an atomic bomb—at least in theory—would have immense destructive power but were unsure about its long-term effects. Nevertheless, the impetus for the Manhattan Project was the fear that the Germans were working to split the atom and create a fission bomb—and if successful, would have a clear path to victory over the Allies.

When Harry S. Truman moved to the White House after the death of President Roosevelt in April 1945, he learned for the first time about the Manhattan Project—and the atomic bomb. A month later, the war in Europe ended with Germany's unconditional surrender.

What was Truman to do about the still ongoing war against Japan? An invasion of the Japanese home islands was being planned. Yet after the heavy casualties inflicted on American soldiers and Marines by the Japanese on Okinawa in April 1945, some advisors believed that the United States would suffer as many as one million killed and wounded in an invasion of Japan.

From the beginning, the American public wanted revenge for the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. Additionally, President Roosevelt announced in 1943 that the war would end only with the unconditional surrender of Japan. These two factors made it highly unlikely that the U.S. and its Allies would reverse course to seek some sort of negotiated peace. Yet Truman also understood that the American people, even if they agreed with unconditional surrender as a goal, had been at war since December 1941 and, having defeated Nazi Germany, might be unwilling to pay such a heavy price in American lives. Not only would soldiers who had just defeated the Germans in Europe need to be deployed to Asia for the invasion of Japan, but military strategists believed that building a logistical base for the amphibious assault would be equivalent to moving the city of Philadelphia to the Pacific Theater. The Navy suggested a blockade of Japan as an alternative to an invasion but acknowledged that such an operation might take years to bring Japan to its knees, if ever.

Historians will continue to argue about whether it was necessary for the U.S. to drop the atomic bombs to end the war. But the better question is whether it was reasonable for President Truman to make the decision, based on the facts as he knew them at the time. Truman had three good reasons.

- The Japanese were unwilling to accept the demand for an unconditional surrender, chiefly because they feared the Allies might insist Emperor Hirohito give up the throne.

- Using the atomic bomb promised to end the war quickly; an invasion of Japan would lengthen the fighting for at least another 24 months, perhaps longer.

- Finally, employing the bomb would save thousands and thousands of American lives—and also Japanese lives. For Truman, who had seen combat in World War I and knew the horrors of war, this third reason seems to have been the most important in his decision to use the atomic bomb.

When you consider that it was only after the second bomb was dropped that the Japanese agreed to surrender, it is reasonable to believe that any invasion of Japan would have been met with significant—and bloody—resistance. Given what we now know about nuclear weapons, few human beings want to see an atomic bomb used again in an armed conflict. However, Truman’s decision ended the war with Japan, and given what he knew at the time, his actions were reasonable.

When you consider that it was only after the second bomb was dropped that the Japanese agreed to surrender, it is reasonable to believe that any invasion of Japan would have been met with significant—and bloody—resistance. Given what we now know about nuclear weapons, few human beings want to see an atomic bomb used again in an armed conflict. However, Truman’s decision ended the war with Japan, and given what he knew at the time, his actions were reasonable.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party