June 25th: Remembering the Forgotten Korean War

Joseph Seeley is Assistant Professor in the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. He is a specialist in the history of Korea, the Japanese Empire, and East Asian environmental history. His forthcoming book, Border of Water and Ice (October 2024), examines the Yalu River boundary between northern Korea and China during a period of Japanese expansion in the region. Seeley has also published on topics such as animal disease control in colonial Korea, US-Korean diplomatic history, Korean tiger-human relations, and the history of Japanese colonial zoos in Seoul and Taipei.

Joseph Seeley is Assistant Professor in the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. He is a specialist in the history of Korea, the Japanese Empire, and East Asian environmental history. His forthcoming book, Border of Water and Ice (October 2024), examines the Yalu River boundary between northern Korea and China during a period of Japanese expansion in the region. Seeley has also published on topics such as animal disease control in colonial Korea, US-Korean diplomatic history, Korean tiger-human relations, and the history of Japanese colonial zoos in Seoul and Taipei.

Seventy-four years ago today, more than 70,000 North Korean troops invaded South Korea, marking the start of the Korean War.

For Koreans then and now, June 25th is a date that lives in infamy. The war itself is called the “6-25 War” or simply “6-2-5” in South Korea. By contrast, in the United States, the significance of this date and the Korean War itself is often forgotten.

But on this date of June 25, as we stand just one year away from the 75th anniversary of the Korean War’s outbreak, it is worth recognizing how the consequences of this conflict continue to reverberate globally and in our UVA community.

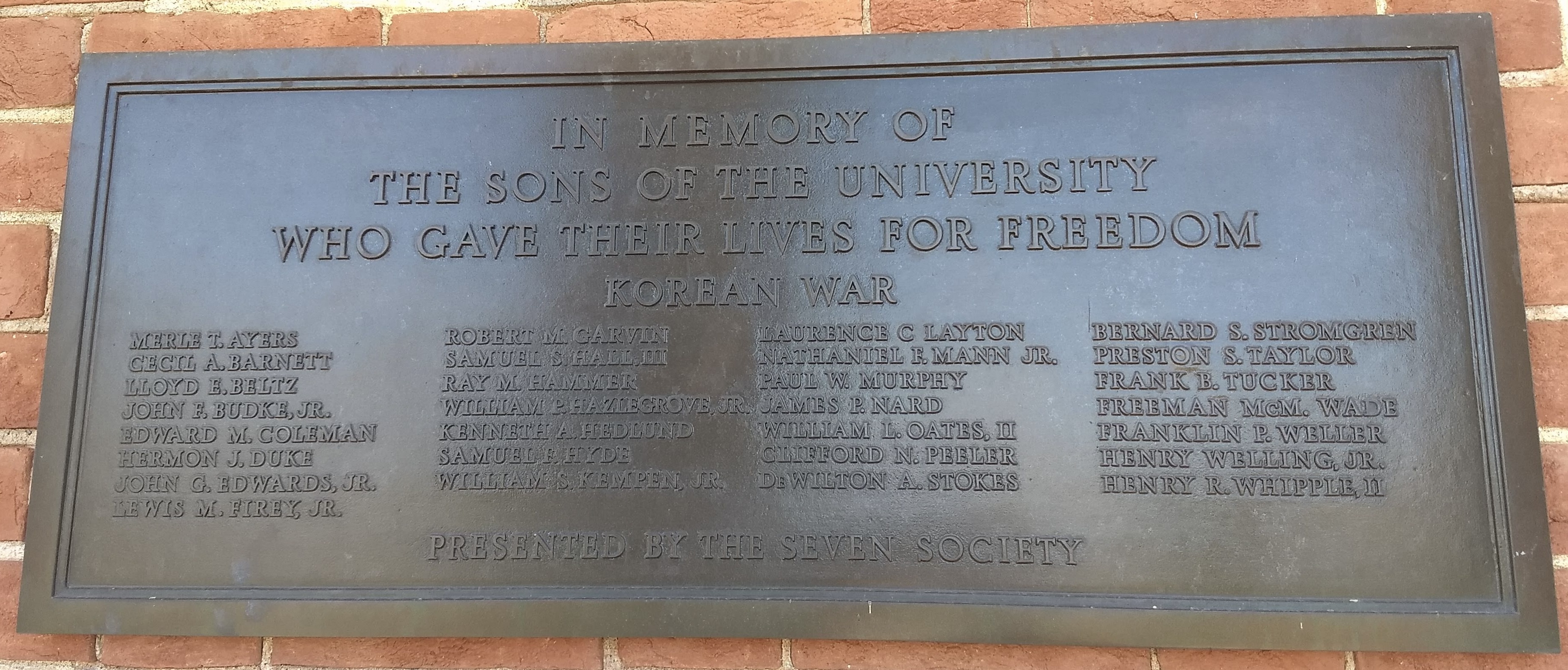

When I lecture about Korean War history at UVA, I often show students an image of a plaque on the north side of the Rotunda that honors “the sons of the university that gave their lives for freedom” in Korea. The twenty-nine ‘Hoos listed each had their dreams, hopes, and aspirations cut short on the bloody battlegrounds of Korea. What far-off events led these UVA students and alum from Virginia to Korea?

The violence that broke out on June 25, 1950, had roots in earlier events. After centuries of proud independence, Korea was violently annexed by the Japanese Empire in 1910. This colonial period—one I analyze extensively in my research—lasted until the end of World War II in 1945. But the joy of Korean “liberation” from oppressive imperial rule proved short-lived. Immediately afterwards, Korea was divided into two zones of occupation by American and Soviet leaders, who shortsightedly deemed Koreans incapable of self-governance.

With worsening Cold War tensions, what was supposed to be a temporary partition resulted in opposing Soviet and US-supported regimes. Unable to reconcile their growing differences, tensions between North and South reached a boiling point that fateful morning of June 25. US and allied forces under the aegis of the recently organized United Nations intervened to support the South. In response, the People’s Republic of China, with air support from the Soviet Union, sent thousands of troops to support their beleaguered Communist ally.

After three years of intense fighting, the war ended not with a peace treaty but with an armistice—essentially a protracted cease-fire. The peninsula was still divided between two hostile powers. All that was new was the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a 160-mile-long corridor of barbed wire and minefields along the 38th Parallel that rendered this division even more visible.

Every recent news headline about North Korean missile launches reminds us that the war of 6-25 has not ended. US troops remained stationed in Korea, and every year that passes since 1950 seems only to widen the economic and cultural gaps between the once-unified halves of the Korean Peninsula.

Beyond geopolitics, the trauma of 6-25 also shapes our local UVA community in different ways. In addition to the names inscribed on the Rotunda plaque, the Korean War is also family history for many students taking my Korean history classes. Some of them have grandparents who fought in the war. For many Korean-American students, the trauma of war and national division is reflected in the stories of refugee grandparents who previously lived north of the 38th Parallel but fled south for their lives during the conflict.

Today, we navigate a world of continued wars and divisions in not only Korea but also Eastern Europe and the Middle East. It is appropriate, I think, for those of us at UVA and beyond to reflect a bit on the legacies of “6-25” and what they mean for us.

For students in my classes, learning about the Korean War gives greater insight into important issues still affecting East Asia, such as the US military presence in South Korea or China’s continued support for North Korea. Discussing Korea’s tragic division in 1945 also reminds students, tomorrow’s diplomats and policy-makers, of the devastating consequences of ignoring local voices when making decisions of international import. The fact that the conflict started and stopped essentially where it began, only to have so many lives extinguished in the meantime, is a harrowing reminder of the depravity and ultimate futility of war. History might not have all the answers to current problems, but studying history helps us develop keener empathy for others and the knowledge to learn from our predecessors.

- Let food be thy medicine…

- Leibniz’s Lost Language – ‘Characteristica Geometrica’ and the Symbolic Art of Mathematics

- Sign Language Is A Human Right for the Deaf

- UVA Club of Charlottesville Presents: Hoos Stories

- UVA Club of Washington DC: How to Handle Disappointing Grades

- UVA Club of Baltimore: Monthly Virtual UVA Committee Meetings