Contemplation and the Hill of Difficulty

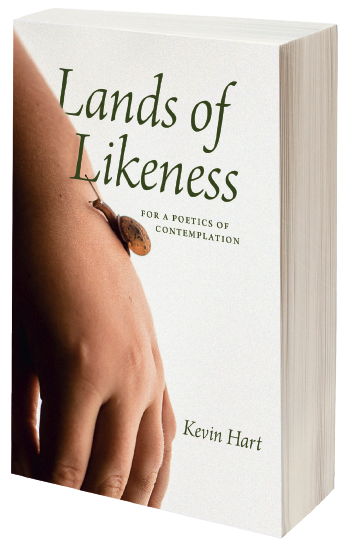

Kevin Hart is Edwin B Kyle Professor of Christian Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. He is the author of eleven poetry collections including Wild Track: New and Selected Poems and Barefoot. His most recent books are Lands of Likeness: For a Poetics of Contemplation (University of Chicago Press, 2023), which represents his Gifford Lectures for 1999-2023, and Contemplation: The Movements of the Soul (Columbia University Press, 2024).

Kevin Hart is Edwin B Kyle Professor of Christian Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. He is the author of eleven poetry collections including Wild Track: New and Selected Poems and Barefoot. His most recent books are Lands of Likeness: For a Poetics of Contemplation (University of Chicago Press, 2023), which represents his Gifford Lectures for 1999-2023, and Contemplation: The Movements of the Soul (Columbia University Press, 2024).

Giving the Giffords

The greatest honor in my field, Christian Theology, is to give the Gifford Lectures. For the past 130 years, the theme of the series has been “natural theology.” When I was invited by Glasgow University to be a Gifford Lecturer, I reflected that there are two ways of regarding natural theology. The first is to weigh evidence from the natural world for the existence of God. The second is to see what the natural powers of the mind can tell us about God, beginning with whether or not God exists. I was trained in both approaches, but both seemed to be largely exhausted. Was there another way to address natural theology?

For decades, I had been reading, teaching and writing on Romantic and Post-Romantic poetry. I knew that much of it was concerned with one or another version of natural religion. The great Romantic poets looked to nature to find Spirit, or they looked within and reflected on their own subjectivity: not the imago dei of Christian orthodoxy, but a deep interiority that testified to their rich spiritual lives. Reflection on both sorts of natural religion constitutes a mode of “natural theology.” It has never attracted argument or proof in the styles of philosophy or theology, but it has involved contemplation. Now contemplation had been a vibrant theme of theology until the Quietist controversy in the seventeenth century; thereafter, it hid in religion and sought refuge in the arts.

For decades, I had been reading, teaching and writing on Romantic and Post-Romantic poetry. I knew that much of it was concerned with one or another version of natural religion. The great Romantic poets looked to nature to find Spirit, or they looked within and reflected on their own subjectivity: not the imago dei of Christian orthodoxy, but a deep interiority that testified to their rich spiritual lives. Reflection on both sorts of natural religion constitutes a mode of “natural theology.” It has never attracted argument or proof in the styles of philosophy or theology, but it has involved contemplation. Now contemplation had been a vibrant theme of theology until the Quietist controversy in the seventeenth century; thereafter, it hid in religion and sought refuge in the arts.

Contemplation had once focused intently on revealed truth, especially Christ as Truth, but in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was partly freed from that obligation: philosophers such as Kant and Schopenhauer affirmed nature as an appropriate object to contemplate. At the same time, poetry became open to contemplation not because it became philosophical but because it could not be assimilated into philosophy. Romantic and post-Romantic poetry has tended to ponder its statements, revise them in the process of composition, and circle around a topic or an emotion rather than reach a settled view that could be rationally defended. One can see this in reading a wide range of poetry, from Wordsworth’s The Prelude to Wallace Stevens’ Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction. Just as criticism of Romantic poetry proved to be a new way of regarding natural theology, so too contemplation, natural and religious, suggested how to read that poetry. Lands of Likeness, my Gifford Lectures on contemplation, shows how the practice of contemplation, in which we seek to become more and more like the deity, helps us to read poems which, through their use of metaphor and other figures, are themselves “lands of likeness.” The book indicates how to read poets as different as G. M. Hopkins, Wallace Stevens, A. R. Ammons, and Geoffrey Hill.

What the Giffords Gave Me

Having completed my duties as Gifford Lecturer, I decided to write a shorter book just on contemplation that could be read by anyone at all. This is Contemplation: The Movements of the Soul (Columbia UP, 2024). It introduces readers to different understandings of contemplation, Christian and otherwise, and explains various ways of practicing it. I would like the book to be widely read, outside the academy as well as within it, since contemplation has the power to change people’s lives. One can still the noisy hive of the mind; one can understand more things (and understand them more deeply); one can become more compassionate. These virtues are largely lost in modern culture, even religious culture, and yet they are profoundly needed. Schools and colleges do little to teach them. We train the analytic part of the mind and leave the contemplative part to slumber.

Having completed my duties as Gifford Lecturer, I decided to write a shorter book just on contemplation that could be read by anyone at all. This is Contemplation: The Movements of the Soul (Columbia UP, 2024). It introduces readers to different understandings of contemplation, Christian and otherwise, and explains various ways of practicing it. I would like the book to be widely read, outside the academy as well as within it, since contemplation has the power to change people’s lives. One can still the noisy hive of the mind; one can understand more things (and understand them more deeply); one can become more compassionate. These virtues are largely lost in modern culture, even religious culture, and yet they are profoundly needed. Schools and colleges do little to teach them. We train the analytic part of the mind and leave the contemplative part to slumber.

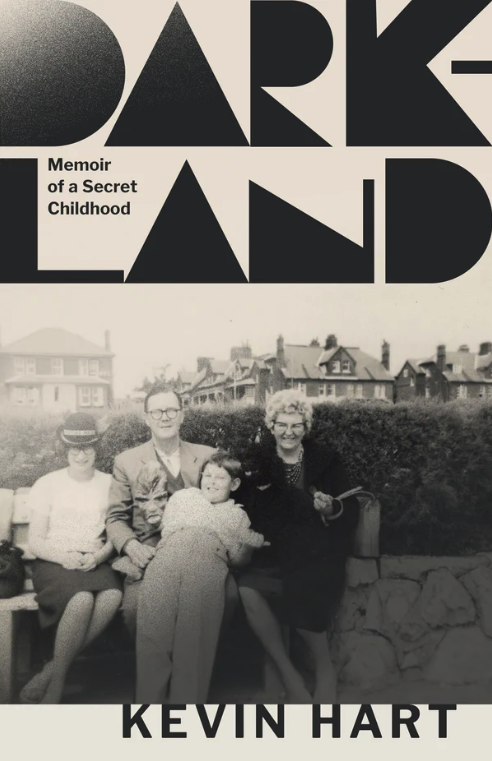

My reflections on contemplation in education draw deeply from my childhood in working-class London. It was an education marked by economic and spiritual poverty, silence, and violence. This is one of the many themes of my memoir, Dark-Land: Memoir of a Secret Childhood (Paul Dry Books, 2024). The title “Dark-Land” comes from John Bunyan’s allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress, which charts Christian’s path up the Hill of Difficulty. Contemplation has helped me climb that path. I think my story is, in its own way, everyone’s story, and I hope that anyone can be helped up that hill by reading it.

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Washington DC: December Book Club