Transition Tradition: Presidential History Lessons

Following the November U.S. elections, Barbara A. Perry comments on the tradition of presidential transitions. Perry (@BarbaraPerryUVA) is the Gerald L. Baliles Professor and Director of Presidential Studies at the University of Virginia‘s Miller Center.

Following the November U.S. elections, Barbara A. Perry comments on the tradition of presidential transitions. Perry (@BarbaraPerryUVA) is the Gerald L. Baliles Professor and Director of Presidential Studies at the University of Virginia‘s Miller Center.

We welcome your comments on this post below.

Transition Tradition: Presidential History Lessons

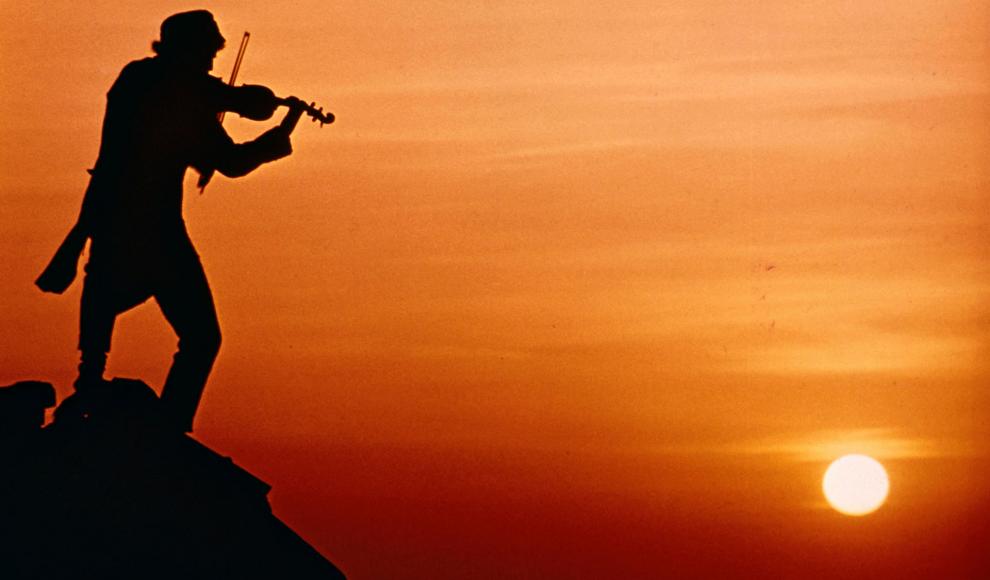

In the classic Broadway play and Hollywood film, Fiddler on the Roof, the main character, Tevye, compares hardscrabble life in his pre-revolutionary Russian shtetl to a violinist straddling a pitched roof as he plucks a haunting tune, like the poor villagers who scratch out a living while trying to stay upright. “And how do we keep our balance?” Tevye asks. “That I can tell you in one word: tradition!”

Although he is referring to religious norms in the fictional orthodox Jewish community of Anatevka, Tevye’s theme could easily apply to American political mores. All U.S. presidents, whether reaching the two-term limit (set by George Washington’s precedent and then by constitutional amendment) or defeated for reelection, have left office peaceably and often with an offer to assist the incoming president in the smooth transference of power.

The Presidential Transitions Act of 1963 codified this passing of the presidential torch and for good reason. Section 1 states that the legislation was to “promote the orderly transfer of the executive power in connection with the expiration of the term of office of a president and the inauguration of a new president.” Not surprisingly, in the midst of the Cold War’s nuclear brinksmanship, the law observed that “[a]ny disruption occasioned by the transfer of the executive power could produce results detrimental to the safety and well-being of the United States and its people.”

Now the threat to our “safety and well-being” is viral and economic. The Miller Center’s non-partisan Presidential Oral History Program has spent the last four decades gleaning experiences from presidencies, starting with Gerald Ford and including Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama. From these several hundred interviews of presidents, vice presidents, Cabinet secretaries, presidential advisors, and Congressional leaders, we have learned the lessons of presidential transitions from those who experienced and facilitated them:

Be civil. After the vitriolic 2000 election, decided by fewer than 1,000 votes in Florida and the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore, a disappointed Vice President Al Gore immediately conceded the outcome to Texas Governor George W. Bush in a gracious speech to the American people. Rumors spread that when the Bush team arrived at the White House on Inauguration Day, departing Clinton staffers had removed the W from keyboards. Harriet Miers, Bush’s White House staff secretary and counsel, told the Miller Center, “I don’t remember anything except responsiveness and helpfulness” from the outgoing Clinton team. She called media reports of missing W keys “a myth. . . . I think there might have been an instance or two of something like that, but to my knowledge, it was blown out of proportion . . . I never saw any evidence of it.”

Do your homework, whether coming in or going out. Miers reported that even though the Supreme Court didn’t hand down its final decision in the presidential election recount case until December 12, short-circuiting the official transition period for Bush, she found that the “materials that were done, describing the various offices, I thought were excellent.” Outgoing Clinton officials said, “come in and we’ll show you where we are . . .”

Accept defeat gracefully. Josh Bolten, who served the George W. Bush administration as deputy chief of staff for policy, Office of Management and Budget director, and chief of staff, had also worked for George H. W. Bush as director of legislative affairs. He had a poignant memory of leaving after the first Bush lost his 1992 reelection campaign: “I remember being one of the last people out of the White House on—I think it must have been January 19th of ’93 . . . I just remember being profoundly moved by looking around the West Wing and seeing nothing on the desks, nothing on the bookshelves. It was wiped clean. . . . I was moved because it is a profound thing about our democracy . . . Just thinking what an incredible thing it is about our democracy that we can have this peaceful and abrupt transition of authority and power.”

Appreciate the process. Former Democratic leader in the House of Representatives, Congressman Richard Gephardt, told the Miller Center that after the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore settled the 2000 election in Bush’s favor, “I remember two things came to my mind. One was that I was horribly disappointed and not in agreement with what they had decided and thought it was a miscarriage of justice. But having said that, I also believe that Vice President Gore’s reaction to it was the correct reaction . . . I remember worrying that there could be demonstrations, violence, and that in probably any other country there would be. I was wondering if Americans would rise to the occasion and, as Gore was, put up with this, even though you hated the result. That to me has always been the essence of the majesty of democracy. I’d always say to my members in Congress, in a democracy, process is everything. I said that because in a democracy if people feel there is a process that is legitimate and fair and reasonably well run, then they’ll put up with bad outcomes, even though they are very angry. If you lose that process, people resort to violence.”

Don’t launch a military mission during the transition. Former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and secretary of state for the Clinton administration, Madeleine Albright, reported in her oral history that “Somalia had started out as a humanitarian mission and was started during the transition [from the Bush 41 to the Clinton presidencies]. I think probably, I don’t know enough about this story, but the decisions made by [Bush National Security Council director] Brent Scowcroft, particularly to go into Somalia, how much consultation he actually had with the Clinton people. I was doing process; I wasn’t doing that issue as much, but it’s a real decision for someone to launch a big thing like that in the middle of a transition. Then obviously that mission changed to a military incursion that went badly for the new Clinton administration.”

Pay it forward. In his just-released memoir, A Promised Land, former President Barack Obama reports that “following a long tradition, the Bushes invited Michelle and me for a tour of our soon-to-be-home . . .Whether because of his respect for the institution, lessons from his father, bad memories of his own transition . . . or just basic decency, President Bush would end up doing all he could to make the eleven weeks between my election and his departure go smoothly.” All the White House offices furnished detailed user manuals to the incoming Obama officials. Bush staffers generously offered their time to answer questions and allowed their future replacements to shadow them. After the unanticipated Trump victory in 2016, Obama returned the favor and immediately invited the 45th president-elect for a legitimizing meeting and photo-op in the Oval Office.

Tevye was right. Tradition helps us keep our balance—even on the ever-shifting landscape of American democracy. Indeed, it upholds the very foundations of our republic.

- Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

- From “Jimmy Who?” to “What Would Jimmy Do?”

- Washington’s Bold Gamble: Christmas Day 1776

- UVA Club of Pasadena: Cavs Care Gathering at the Raymond

- UVA Club of Boston: UVA Men's Basketball Game Watches

- UVA Club of Richmond: Tour of the Valentine Museum