Pandemics and the Power of History

What lessons has the past taught us about containing diseases? Christian McMillen suggests that particular social and biological conditions historically have given rise to the emergence of epidemics and pandemics. McMillen is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History and associate dean for the social sciences in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

What lessons has the past taught us about containing diseases? Christian McMillen suggests that particular social and biological conditions historically have given rise to the emergence of epidemics and pandemics. McMillen is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History and associate dean for the social sciences in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

Pandemics and the Power of History

I am a historian. I think about how the past created the world in which we now live. But these days, amidst the coronavirus pandemic, I find the past, present, and future colliding with one another.

Because epidemics and pandemics have been part of human history for millennia, there are many things that their histories can teach us. For one, epidemics and pandemics force us to reckon, again and again, with the obvious fact that the natural, or non-human, world has a powerful effect on the human world. At the same time, we must keep in mind that there is not anything natural about why infectious diseases strike when they do or why they affect one place or people and not another. As David Arnold wrote about cholera in mid-nineteenth century India, “Like any other disease, it has in itself no meaning: it is only a micro-organism. It acquires meaning and significance from its human context, from the ways in which it infiltrates the lives of the people, from the reactions it provokes, and from the manner in which it gives expression to cultural and political values.” Just as our values give meaning to microorganisms, the conditions that gave rise to epidemic and pandemics only occur within particular historical contexts, and thus infectious diseases only emerge as epidemics when particular social and biological conditions are present.

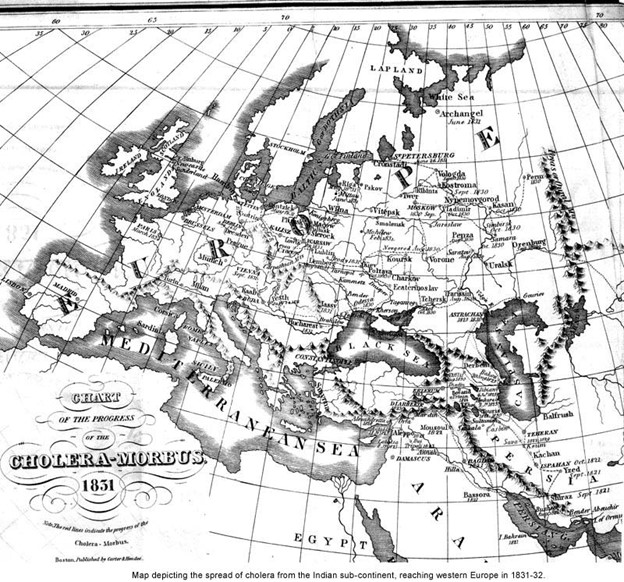

Take cholera. While there is strong evidence that cholera had been epidemic in India in the eighteenth century, it was not until the 1820s that it traveled the globe. Key developments in world history made this possible: British colonialism in India increased travel and trade between the East and the West; faster and faster travel by ship, especially as steam replaced sails; railway lines continued to link huge swaths of previously unconnected space such as the Mediterranean and Red Seas; the opening of the Suez Canal accelerated the pace of travel between parts of the globe; increased urbanization across Europe; the reasons go on.

The point might be obvious, but it’s one I want to stress: epidemic diseases do not occur outside of a human context. This is why understanding their history is so obviously important.

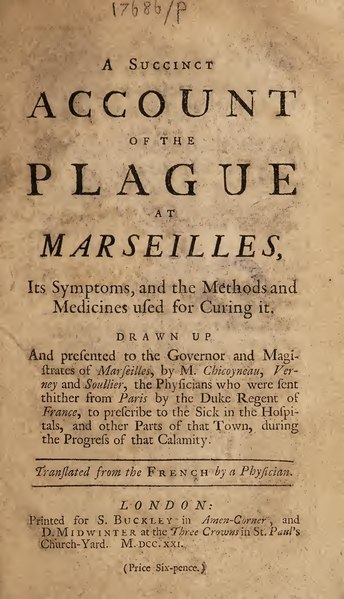

Epidemics and pandemics always have a disproportionate effect on the poor and the marginalized. *Paul Farmer, one of the co-founders of Partners in Health, has called epidemic diseases like tuberculosis “biological expressions of social inequality.” We have known this for centuries. Writing of the plague in Marseilles in 1720, a doctor wrote the following about a neighborhood spared of the pestilence: “The streets are wide, the houses large, and inhabited chiefly by persons living in a state of opulence, and such are always the last attacked by a contagion, on account of the means they have to place themselves out of its reach.” We are seeing this now, tragically, as Covid 19 makes its way into the places least able to contain it. When cholera began to make its way out of India in the 1820s, “It,” as the historian Mark Harrison wrote, “defined the contours of a new world economy, revealing its connections and also, more starkly, its divisions.” The same is true of the coronavirus.

Since the laboratory revolution of the late nineteenth century, and especially since the invention of antibiotics and other “miracle drugs” in the years after World War II, we have over-relied on technology and biomedicine to keep us safe while at the same time, steadily but surely, dismantled any semblance of a robust public health infrastructure. The result has been overconfidence and unrealistic promises about the demise of disease. In the past century, and in our current one, a dangerous side effect of medical progress has been an irresponsible optimism concerning the power of biomedicine to rid the world of epidemics. Overconfidence became especially prominent as a result of the laboratory revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

With the discovery of antibiotics in the 1940s, confidence in medicine only accelerated—and kept doing so in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s in the “golden era” of medicine. People began to talk about the eradication of infectious diseases. Infectious disease specialist T. Aidan Cockburn claimed in Science in 1961 that “we can look forward with confidence to a considerable degree of freedom from infectious diseases at a time not too distant in the future.” Walsh McDermott, a prominent TB and international health expert, claimed in the early 1960s that because of antibiotics, the control of TB “is one of the few instance to date in which a major disease can be decisively altered without having to await improvement in the social infrastructure.” This is a remarkable and dangerous claim. And in 1973, at the height of biomedical optimism, Frank MacFarlane Burnett, a Nobel prizewinner in biology from Australia, wrote in one of the most widely used textbooks in medical education, The Natural History of Infectious Disease, that because infectious diseases had largely been done away with “one of the immemorial hazards of human existence has gone.”

This optimism was wildly misguided. By 1973, HIV/AIDS, one of the most devastating infectious diseases in human history, was lurking and ready to take off. When it made its public debut less than a decade after Burnett’s claims, any bluster about the death of infectious disease by the hand of biomedicine or hope of living in a world free of pestilence disappeared. HIV/AIDS was a new infectious disease thriving in a world once thought—by some, anyway—to be on the verge of being rid of such menaces.

None of this means that drugs or medical research are not essential for the control of epidemics. Anti-retroviral therapy, an extraordinary discovery by any measure, has been essential in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Yet, access has been uneven. Since its discovery in the 1960s, oral rehydration therapy for cholera has been lifesaving. But it does nothing to address the reasons why millions of people in the global south are drinking feces-infested water. TB can be cured with antibiotics, yet we have more TB now than at any other time in world history. The very simple point is that there is a relationship between disease and social conditions, conditions that do not exist everywhere, and that will not be alleviated with biomedicine.

No historian could have predicted the current coronavirus pandemic. But most historians of epidemics and pandemics are likely unsurprised by some of its key features: the power that the natural world still holds over human life; the disproportionate effect of pandemics and epidemics on the poor and the marginalized; and the over-reliance on biomedicine to the exclusion of a robust public health infrastructure.

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Washington DC: December Book Club