Speak, Memory: Poetry and Survival After the Atomic Bombings

August 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of WWII. Chad R. Diehl gives us a personal and poignant look at a unique bombing survivor’s representation of trauma through the Japanese art of tanka. Diehl is an assistant professor in the Corcoran Department of History in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

August 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of WWII. Chad R. Diehl gives us a personal and poignant look at a unique bombing survivor’s representation of trauma through the Japanese art of tanka. Diehl is an assistant professor in the Corcoran Department of History in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

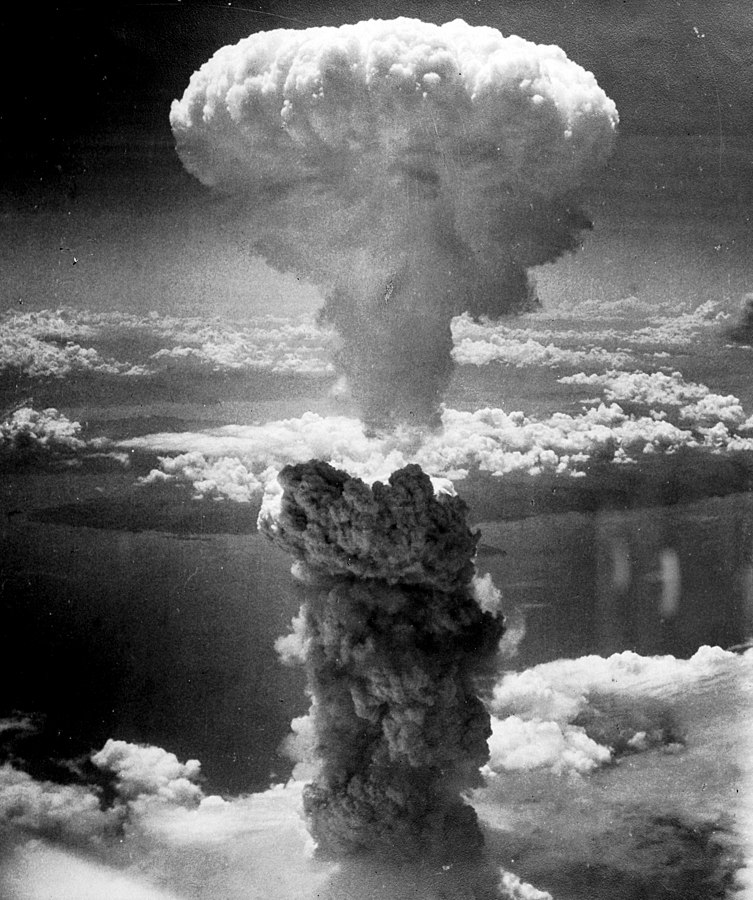

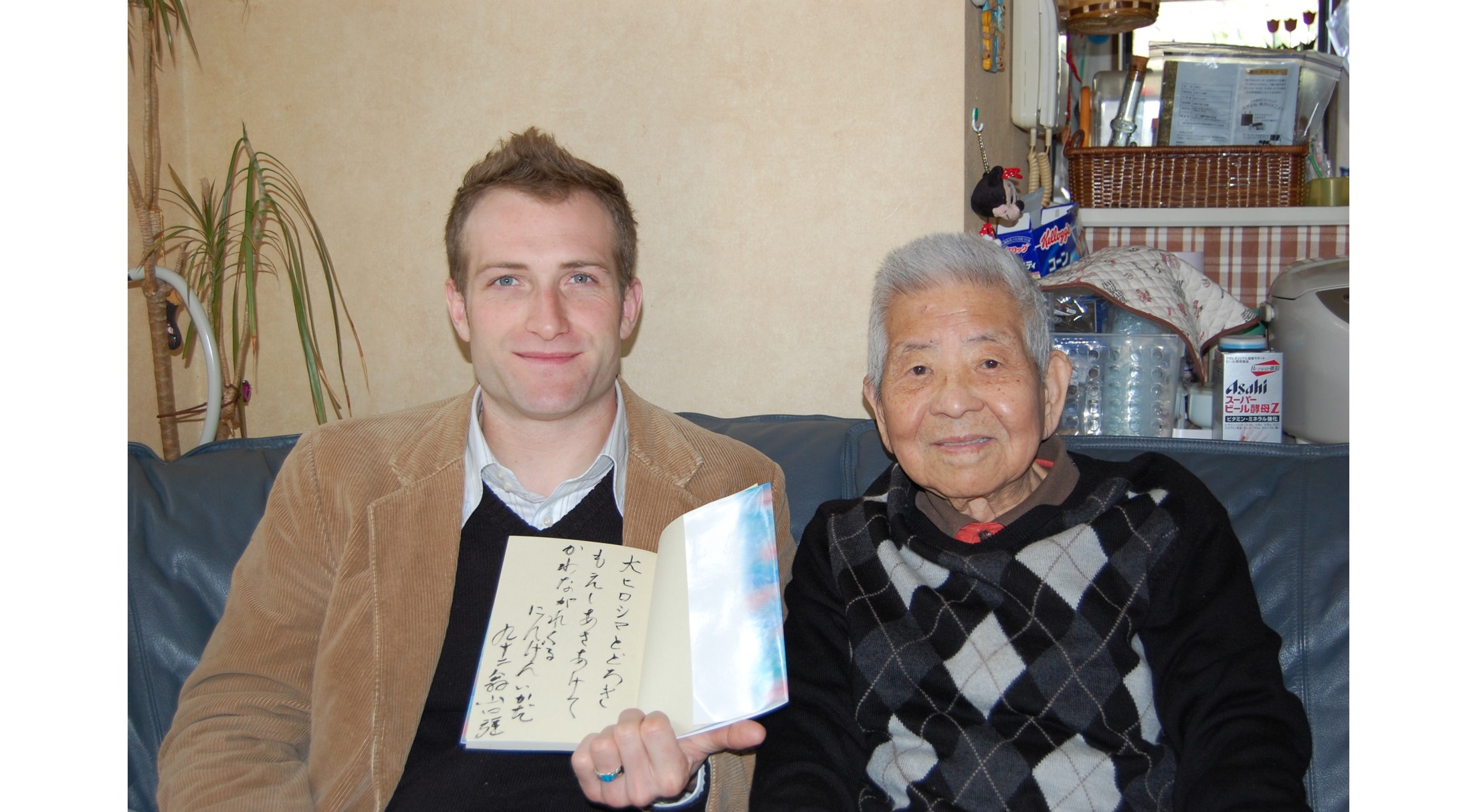

Tsutomu Yamaguchi witnessed and survived two atomic bombings in just three days. He was in Hiroshima for work on August 6, 1945, endured some burns on his left arm and face, and boarded a train for his hometown of Nagasaki on August 7. As he related to me over castella-cake and tea at his home in Nagasaki on a muggy July afternoon in 2009, when he saw the mushroom cloud rising above the second city on August 9, 1945, he was certain that it had chased him down from Hiroshima.

The Second World War ended in 1945, but Yamaguchi lived with physical and psychological trauma from the bombings until he died of cancer in 2010. Writing tanka, a kind of short-form poetry with strict rules of composition, provided at least some catharsis over his long life. He had been an expert tanka composer since well before the bombings, so he naturally embraced that medium of expression when he sought to identify, isolate, and work through his traumatic memories.

In the last few years of his life, after his son died of cancer in 2005 (his wife died in 2008, also from cancer), he gave public speeches about his double-atomic-bombing experience at a variety of venues, including museums in Nagasaki, but also at Columbia University and the United Nations when he traveled to New York in 2006, the first and last time he ever traveled outside of Japan. As part of his speeches, Yamaguchi sometimes shared his tanka when he wanted to convey to his audience the horrific scenes that he witnessed.

Conventional narrative modes of storytelling often failed Yamaguchi and other survivors who have struggled to capture and relate their trauma through language. The non-linear nature of poetry seems to reflect and therefore better represent their trauma as they had actually lived it. Tanka provided Yamaguchi with a framework that helped suture together a fragmented—but not incomplete—memory of the bombings. Other survivor poets found the rules of tanka and haiku too restrictive to sufficiently represent their experience, so they instead turned to a free-verse style to access the representative power of poetry more fully.

Regardless of the form, the poetic process provided a medium for catharsis to many survivors. For Yamaguchi, composing tanka became a way to tidy up the past, so to speak, to “normalize” daily life to the extent possible so that he could live. A trauma never disappears; it is simply managed.

Regardless of the form, the poetic process provided a medium for catharsis to many survivors. For Yamaguchi, composing tanka became a way to tidy up the past, so to speak, to “normalize” daily life to the extent possible so that he could live. A trauma never disappears; it is simply managed.

When I lived with Yamaguchi and his daughter’s family in the summer of 2009, it was clear that the weight of his traumatic past had not dissipated since 1945. When Yamaguchi recited certain poems to me, to a documentary filmmaker, or to an audience of high school students, his voice often cracked as his face betrayed the presence of a dark memory inaccessible to anyone but himself. These moments—when the past would rupture the present—also illustrated the limits of language, even poetry, to truly capture the human experience of mass destruction.

In one tanka, Yamaguchi describes a grotesque scene that he witnessed while also relating the nature of traumatic memory:

…………They [corpses] are piled atop one another high.

………….And the ground will never dry.

………….It is soaked with the fat of all the people

………….who burned and died.

For Yamaguchi, and, indeed, all survivors, traumatic memories persist, piled high and weighing heavily on their lives, as enduring as the oily dirt beneath them. This poem in particular haunted Yamaguchi. When he would read it, even more than six decades after witnessing the scene he describes, he would be choked with tears and momentarily paused before completing the recitation [see second tanka recited here]. In these moments, the fault lines in the calm of the present became apparent as the poem pulled a haunting past out of the shadows and into view.

Getting to know Tsutomu Yamaguchi and his poetry in the last four years of his life opened my eyes in more than just academic ways. When I was in high school in 1995, on the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings, I remember seeing a T-shirt that a friend’s uncle wore in my hometown of Gardiner, Montana. The shirt had a simple message: beneath two mushroom clouds were the words, “No Apologies, No Regrets.” My first thought, I remember, was not to wonder whether this kind T-shirt patriotism made a good point or if it could lead to an important dialogue. Rather, I felt for the first time in my life a deep curiosity about the fate of the people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the years and decades after the bombings.

It never dawned on me that fourteen years later I would have the privilege—and the responsibility—of living with someone who witnessed both bombings, and who would reveal to me more about the darkness embedded within the human experience of history than I ever cared to know.

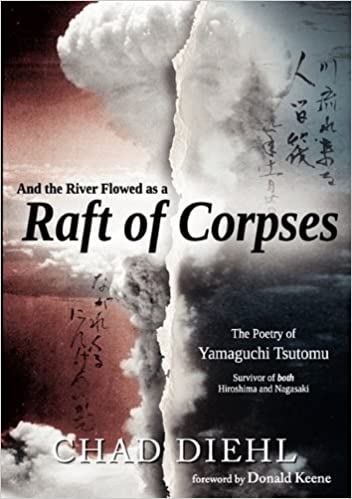

Note: In 2010, Chad Diehl self-published And the River Flowed as a Raft of Corpses: The Poetry of Yamaguchi Tsutomu, Survivor of Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Note: In 2010, Chad Diehl self-published And the River Flowed as a Raft of Corpses: The Poetry of Yamaguchi Tsutomu, Survivor of Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Vietnam: J-Term Farewell Social

- UVA Club of Atlanta: UVA Women's Basketball at Georgia Tech