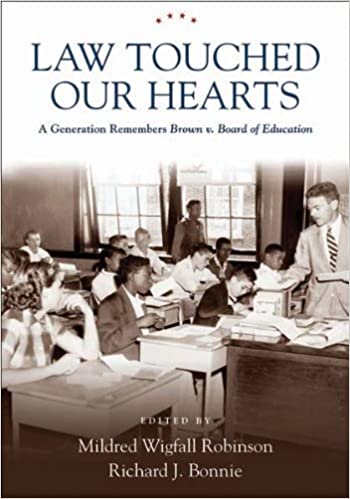

Law Touched Our Hearts: A Generation Remembers Brown v. Board of Education

Mildred Wigfall Robinson has been a faculty member of the University of Virginia‘s School of Law since 1985 and is retiring in May. She shares her story of the impact of the 1954 landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education, throughout her lifetime. Robinson and School of Law colleague, Richard J. Bonnie, have published a collection of forty essays, Law Touched Our Hearts: A Generation Remembers Brown v. Board of Education (Vanderbilt, 2009), about the decision’s effects on the nation’s public school students in the years that followed.

Mildred Wigfall Robinson has been a faculty member of the University of Virginia‘s School of Law since 1985 and is retiring in May. She shares her story of the impact of the 1954 landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education, throughout her lifetime. Robinson and School of Law colleague, Richard J. Bonnie, have published a collection of forty essays, Law Touched Our Hearts: A Generation Remembers Brown v. Board of Education (Vanderbilt, 2009), about the decision’s effects on the nation’s public school students in the years that followed.

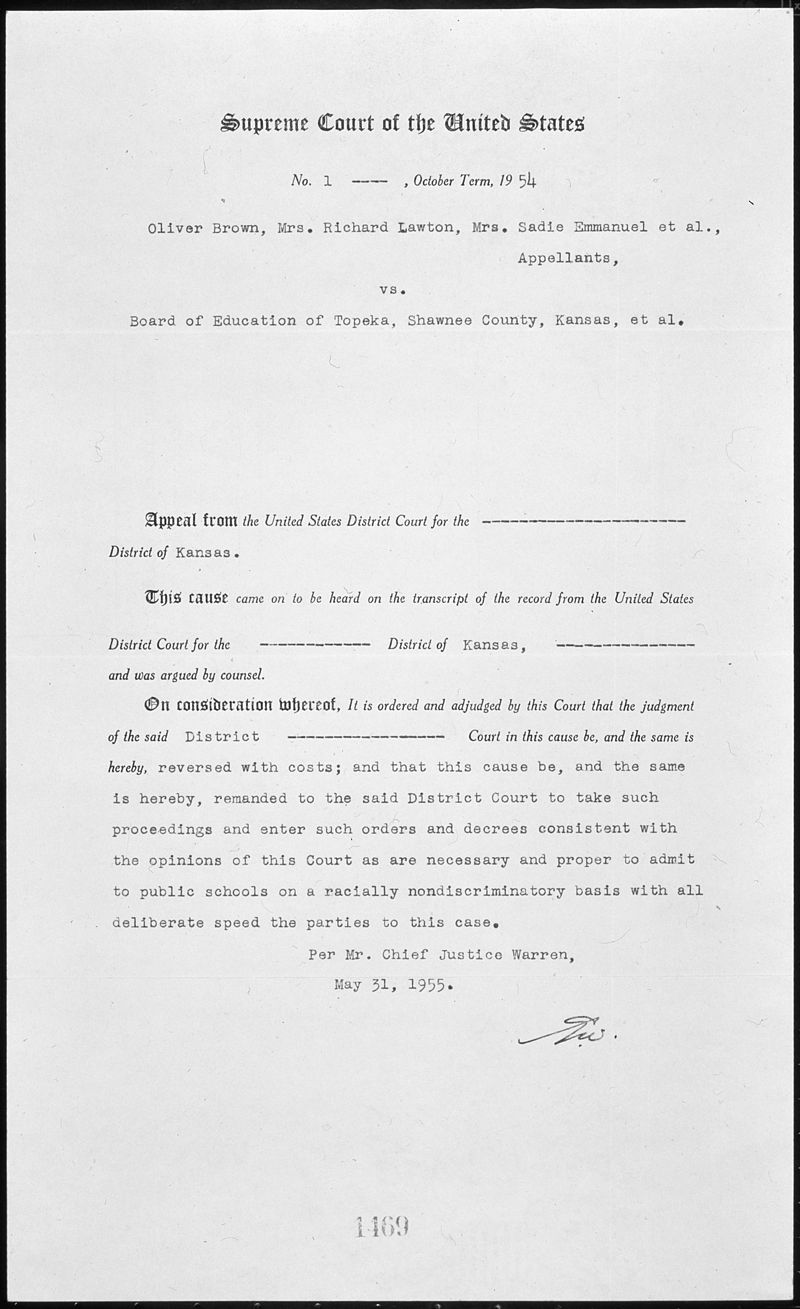

May 17, 2020, will mark the 66th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. Brown was a watershed case in American history. In that 1954 case, the Supreme Court of the United States held that “[I]n the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate education facilities are inherently unequal.”

“Sixty-sixth” anniversaries are not observed! Milestone dates are ordinarily divisible by five or ten. However, as I think of major life events in the shadow of my impending retirement, Brown looms large. In 1954, I was a nine-year-old African American fourth-grader in the Berkley Training County School (BCTS) in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. BCTS was racially separate but (except for accomplished and dedicated teachers) emphatically not equal. May 17, 1954, was a beautiful low-country spring day. Late that morning (and during recess) my father, the school principal, gathered all of us together on the school’s playground to tell us of the decision. We were children. We were excited!! And we were totally innocent with regard to the enormity of what would be demanded of us, our communities, and our families as we moved into the post-Brown era.

In the years that followed, all of my family personally experienced the effect of that decision. I remained in segregated schools through high school as did my oldest brother. My middle brother became one of 12 black students to desegregate and graduate from a 1200-student high school in Cocoa Beach, Florida. The school’s faculty and staff remained all-white during that period. My youngest brother started an all-white Atlanta high school that became all-black over the course of his matriculation there because of white flight. After serving in public schools in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, my mother retired from the Atlanta School System after a successful career first as a teacher and then as a guidance counselor after having been summarily reassigned from a black high school to a white high school in Atlanta late in the 1960s. On the other hand, my father lost his job as a public school principal after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He was unsuccessful in securing a comparable position thereafter. He was thus denied the opportunity to continue to pursue the career that he had loved.

As an adult, first as a law student and then as a member of the legal academy (my dream job with faculty appointments that made me a part of my extended family’s third generation of educators), I realized that Brown’s promise as we children thought we understood it had proven unfulfilled. Instead, it was Congress, through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that finally dismantled the apparatus of de jure public school segregation – and societal segregation generally. I understood that glaring inequalities in our society remained, however. As such, I became (and remain) consumed by a drive to understand and address the myriad ways in which the financial underpinnings of our American system of governance are borne by its citizens. Simply put, my animating principle was that both the benefits and burdens of governance – including financial responsibility – should be equitably allocated. Hence, my work has been in public finance – specifically federal, state, and local tax practice and policy.

Little of my teaching and research revolved directly around the Brown decision. For decades, I never spoke of my personal history with the case with anyone outside of my family. That changed several years after I joined the law school faculty at the University of Virginia. (I had taught at the Florida State University College of Law in Tallahassee, Florida for twelve years prior to my Charlottesville arrival.) A casual conversation with my colleague Richard Bonnie (who had grown up in Norfolk, VA), deepened when we discovered that we were both Brown babies. He and I shared and compared our experiences as children during the years immediately following the Brown decision. We agreed that our stories – as well as stories from others of our generation – needed to be shared. We ultimately collaborated on the five-year project that led to the publication of Law Touched Our Hearts.

Law Touched Our Hearts: A Generation Remembers Brown v. Board of Education (Vanderbilt, 2009) contains forty essays. Each essayist, including both Richard and myself, was a student in one of the nation’s public schools in some part of the United States when the decision was handed down. Each of us wrote of the decision’s personal impact — then and in the years that followed.

Law Touched Our Hearts: A Generation Remembers Brown v. Board of Education (Vanderbilt, 2009) contains forty essays. Each essayist, including both Richard and myself, was a student in one of the nation’s public schools in some part of the United States when the decision was handed down. Each of us wrote of the decision’s personal impact — then and in the years that followed.

The process –almost entirely sui generis — is described in detail in the book’s introduction. The forty personal accounts – written by men and women across a racial spectrum — reflect experiences in the nation’s public schools in the years after 1954. The majority of our schools were segregated either de jure (segregated by law in 1954) or de facto (segregation illegal but common and accepted practice). Taken together, our essays describe a national experience, for we grew up in states literally from Maine and Florida to California. Our commentator noted that “[t]hese are deeply moving personal perspectives on the civil rights era, revealing in vivid detail how children across the nation lived out the dilemmas of race in their families, schools, and neighborhoods.” The book remains one of a kind.

Sharing the impact of the Brown experience — first between the two of us at the law school and then with colleagues nationwide as the project evolved – brought my academic experience full circle. I experienced the beauty of collegial collaboration at a very high level. I rediscovered that personal and intellectual experience and growth are inextricably and validly intertwined. Finally, through sharing my family’s post-Brown experience, I was able to acknowledge and honor the personal sacrifice that my father was forced to make in the convulsive struggle to move the country towards a more inclusive society. For all of these reasons, May 17 will always be an important anniversary for me.

- Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

- From “Jimmy Who?” to “What Would Jimmy Do?”

- Washington’s Bold Gamble: Christmas Day 1776

- UVA Club of Pasadena: Cavs Care Gathering at the Raymond

- UVA Club of Boston: UVA Men's Basketball Game Watches

- UVA Club of Richmond: Tour of the Valentine Museum