The Lawn & Roman Architecture–Part 2

Beware the Ides of March! In this second part of Dylan Rogers’ article about the influence of Roman architecture on Jefferson’s designs for the University, he takes us on a walk down the Lawn from the Rotunda to Pavilion X. Rogers is a lecturer in Roman Art & Archaeology at the McIntire Department of Art in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

Be sure to read Part 1 of this two-part article. We welcome your comments below.

The Lawn & Roman Architecture–Part 2 (of 2)

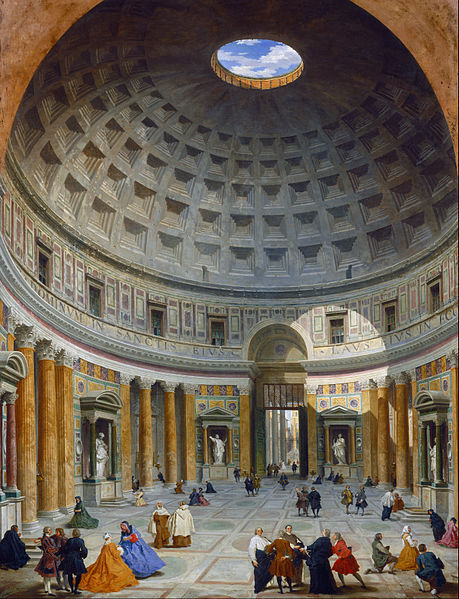

Jefferson’s autopsy of the Roman buildings of southern France would always be on his mind. Indeed, he used his visits to Europe and his fondness for Palladio in his conception of the University. The Academical Village, then, would be centered around an architectural space that was literally founded on Roman traditions, filtered through an early 19th-century lens. So, when I take my students to the Lawn, we start at the Rotunda, the heart of the University. It is modeled on the Pantheon (dedicated AD 126), a structure that had one of the largest uninterrupted domes in history until the 16th century, thanks in part to the Roman concrete used to construct it. Because I can’t take my students on a field trip to Rome during the semester, the Rotunda is an ideal substitute when we discuss the Pantheon. We get to experience and understand the monumentality of the building, especially when we go into the Dome Room, with its soaring heights and oculus (or the opening at the apex of the dome).

Then, we head down the Lawn interacting with all of the Pavilions in particular. Jefferson used each one to tell students, both in the 19th century and today, a story. Pavilions I-III (those closest to the Rotunda) are models of the three traditional orders of architecture (Doric/Tuscan, Ionic, and Corinthian). At this point, I ask them what Pavilion II reminds them of? The correct answer is the Temple of Portunus in Rome—a small little temple close to the Tiber River built in the 2nd century BC—one of the first examples we study in class. The original has a high podium and four Ionic columns on its porch. I ask students what their reaction to the Pavilion is, especially after studying it in class. The answers are endless—but usually, they are centered on the physicality of the experience. You can literally go hug the columns here to get a sense of their scale, their monumentality in space.

The Pavilions serve not only to show students the various elements of those orders but also how the proportions of each differ and change the space around them. Indeed, as you walk down the Lawn, you notice the great variety in the design of all of the Pavilions: Pavilion V with its large Ionic columns taking up two stories, while directly next to it, a two-tiered design of Tuscan columns on top of arcuated piers. This all follows with Jefferson’s desires, as expressed to one of the architects with whom he collaborated, William Thornton: “What we wish is that these pavilions, as they will show themselves above the dormitories, shall be models of taste and good architecture, and of a variety of appearance, no two alike, so as to serve as specimens for the architectural lecturer” (1817). By the time we get to the end, Pavilion X is an architectural fantasy of Jefferson’s, with its slender large-scale Doric columns and a roof capped by a large parapet, a structure not often used in antiquity.

So, with my students, we can see Roman architecture first-hand. We can examine the influences of each building. We can find elements that have been adapted from their ancient models—founded on ancient models, but altered to create something totally new, with new meaning. We get the sense of how architecture interacts with its surrounding environment—because architecture is meant to be experienced. It’s all around us. And on your next visit to the Lawn, I invite you to do the same.

Author’s note: If you want to know more about Jefferson and his passion for Roman architecture, there are a number of resources to explore. In late 2019, the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, hosted the exhibition, “Thomas Jefferson Architect,” which delved into Jefferson’s love of architecture–and its connection to the new Republic’s expression and sense of identity. The exhibition catalogue (DeWitt and Piper 2019) has a number of interesting articles, including one on Jefferson’s travels in Europe to look at Roman ruins and architecture first-hand. The Palladio Museum in Vicenza hosted an exhibit, “Jefferson and Palladio: Constructing a New World,” in 2015-2016, and its catalogue (Beltramini and Lenzo 2015) is a tribute to Palladio’s influence on Jefferson–and the architecture of Virginia in the 19th century. Finally, Wilson 2009 is a classic on how Jefferson conceived of and executed the construction of the Academical Village, teeming with reproductions of his numerous architectural drawings.

Beltramini, G., and F. Lenzo, eds. 2015. Jefferson and Palladio: Constructing a New World. Milan: Officina Libraria.

DeWitt, L., and C. Piper, eds. 2019. Thomas Jefferson Architect: Palladian Models, Democratic Principles, and the Conflict of Ideas. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wilson, R.G., ed. 2009. Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village: The Creation of an Architectural Masterpiece. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Phoenix: Hoo-liday Party