The Lawn & Roman Architecture–Part 1

Beware the Ides of March! Just as March 15th was a turning point in Roman history, so too was exposure to Roman architecture a turning point for Thomas Jefferson. Dylan Rogers, Lecturer in Roman Art & Archaeology, describes how Jefferson’s first-hand observations of Roman sites influenced his design of the University of Virginia as well as the Virginia State Capitol. Rogers teaches at UVA’s McIntire Department of Art in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences.

Beware the Ides of March! Just as March 15th was a turning point in Roman history, so too was exposure to Roman architecture a turning point for Thomas Jefferson. Dylan Rogers, Lecturer in Roman Art & Archaeology, describes how Jefferson’s first-hand observations of Roman sites influenced his design of the University of Virginia as well as the Virginia State Capitol. Rogers teaches at UVA’s McIntire Department of Art in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences.

Be sure to read Part 2 of this two-part article. We welcome your comments below.

The Lawn & Roman Architecture–Part 1 (of 2)

When I teach Roman Art and Archaeology at the University, undeniably, my favorite class the whole semester is when we meet on the Lawn. The majestic architectural endeavor of the Lawn provides the ideal place to show students up close how Roman architecture works in real spaces—not just on the flat screen in Campbell Hall. And this is what Jefferson wanted when he began planning for the University. As early as 1816, he knew that the heart of this place devoted to higher education in central Virginia would be didactic, not only in the classroom but also in the spaces in which students interacted and inhabited. Indeed, in a letter dated 2 April 1816, Jefferson explains to Governor W.C. Nichols how he intended to exhibit “models in architecture of the purest forms of antiquity, furnishing to the student examples of the precepts he will be taught in that art.”

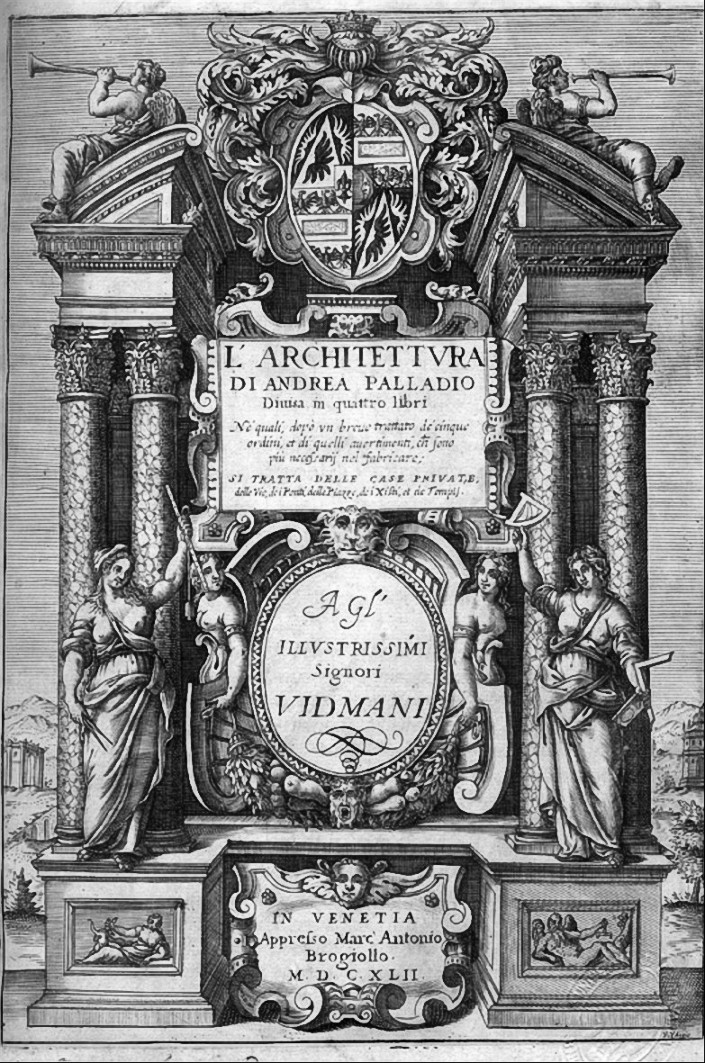

And that is exactly what happened—something that I get to do every semester with my students, two hundred years later. But such an architectural gem is steeped in Jefferson’s rich reading of architectural treatises and actual visits to Roman ruins and sites in Europe. It is widely known that Jefferson read and internalized the important work of the Renaissance architect, Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), active in the region of Veneto in northern Italy. Starting in college, Palladio’s monumental I quattro libri dell’architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), itself influenced by Vitruvius’ famous De architectura (On Architecture), became a bible of sorts for Jefferson, who had never formally trained as an architect. Indeed, his friend Isaac A. Coles once recalled, “Palladio [Jefferson] said was the Bible… you should get it and stick close to it.” Palladio challenged Jefferson to consider traditional Roman architectural forms, often combined with novel manipulations of those forms—thus creating something that felt antique but fresh at the same time. Indeed, Palladio and his work, in part, would spur an architectural movement (often called Neoclassicism), especially in the new United States in the late 18th century that was founded in part on new interpretations of Roman architecture.

When Jefferson served as the Minister to France from 1785-1789, he took a trip to southern France and northern Europe in 1787. While the trip was primarily for business (not like the pleasure-filled Grand Tours that young elite men were taking at the time), Jefferson managed to observe first-hand Roman sites at Nîmes, Vienne, and Glanum near Saint-Remy, amongst others. At Nîmes, Jefferson was struck by the temple known as the Maison Carée, which he had already encountered in the pages of Palladio—and used as a model for his designs of the Virginia Capitol building. But seeing it in person, in what we call autopsy (namely a close inspection of how the architecture itself works and interacts with its surrounding environment), was important for Jefferson, as he realized that he had to change the designs of the Capitol. For example, he shortened the porch from three rows of columns to two, because he observed how the rooms off of the porch would be too dark. When Jefferson went into Italy, probably because of time constraints, he only visited Turin, Milan, and Genoa. Oddly enough, though, he never made it to Vicenza, the epicenter of Palladian architecture, nor farther south to Rome.

Look for Part 2 of “The Lawn & Roman Architecture” in which the author will explore how to visit the Lawn through the lens of Roman architecture’s influence on Jefferson.

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Phoenix: Hoo-liday Party