Reminder of a ‘Last Man’

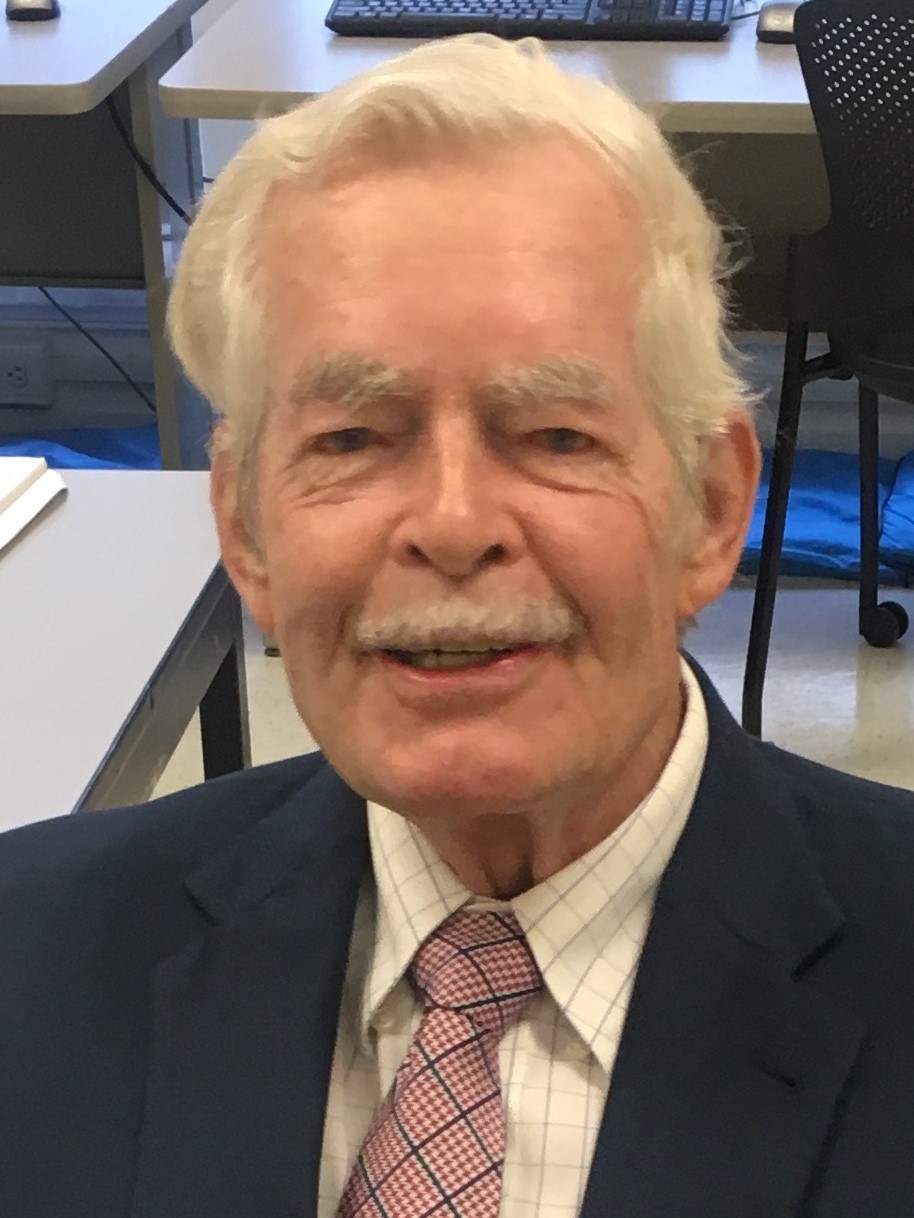

With the Oscar-nominated film, 1917, out in theaters, World War I is a hot topic of conversation among history buffs. C. Brian Kelly remembers Edouard Izac, WWI’s last surviving Medal of Honor recipient and one-time resident of Gordonsville, Virginia–near Charlottesville–who died thirty years ago on January 17. Mr. Kelly is Assistant Professor, Department of English in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia. He teaches news writing and is an author of Best Little Stories from World War I with Ingrid Smyer, College ’81.

With the Oscar-nominated film, 1917, out in theaters, World War I is a hot topic of conversation among history buffs. C. Brian Kelly remembers Edouard Izac, WWI’s last surviving Medal of Honor recipient and one-time resident of Gordonsville, Virginia–near Charlottesville–who died thirty years ago on January 17. Mr. Kelly is Assistant Professor, Department of English in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia. He teaches news writing and is an author of Best Little Stories from World War I with Ingrid Smyer, College ’81.

We welcome your comments below.

Reminder of a ‘Last Man’

The Oscar-nominated film 1917 is one heck of a story, but it gives rise to so many others, including that of a young American Navy lieutenant who once spent 11 days sealed in a World War I German U-boat—no escape possible. But soon after, the same incredibly determined Edouard Victor Michel Izac was to be seen hurling himself through the window of a speeding German train.

His desperate hope then was not merely to escape, but to reach Allied forces and report all he had learned about German U-boat operations.

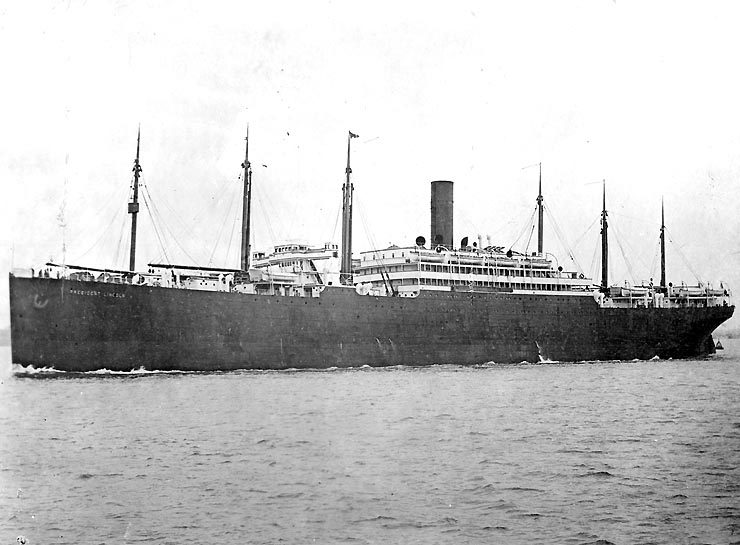

Izac already had survived the sinking of the U. S. troop ship President Lincoln by the same German U-90 that plucked him off a lifeboat and carried him deep into the home port of the German High Seas Fleet.

Recovering from injuries sustained when he leaped through the window of the train, and the beatings that followed, he later deliberately drew the fire of the guards at his prison camp to cover the escape of others, then with a companion POW trudged through mountains to neutral territory—after also swimming the Rhine.

Still later to become a journalist, book author, and U.S. House member from San Diego, California, this same native of Cresco, Iowa, would live to become both the oldest and the last surviving Medal of Honor winner from World War I.

The U. S. Naval Academy graduate’s adventures began with assignment to the captured German passenger liner President Lincoln, followed by its sinking at the hands of the U- 90. The U-boat commander personally told Izac the Lincoln was recognizable even at periscope depth as one of only two six-masted steamships in the world.

In any case, the U-90 sent three torpedoes into the troopship at breakfast time on May 31, 1918, as it was returning home from its fifth trip delivering American troops to France in support of the Allies. From his lifeboat, Izac then watched as the old ship, “turning over gently to starboard, put her nose in the air and went down.” Twenty-six personnel died with her, but nearly seven hundred others survived.

The U-boat commander really wanted to seize the captain of the troop ship rather than settle for a young lieutenant as his prize, but Izac convinced him, falsely, that his own skipper went down with the ship. Thus, it was Izac who was taken away by the U-90 as a prisoner of war, after first being treated to a warming dollop of sherry.

In the days that followed Izac watched closely as the submarine patrolled, hunted other Allied ships, and went through its daily operations. He was treated well, allowed to sleep in the officers’ Ward Room, even to play bridge with them.

It all was very affable, but that wouldn’t last for very long. Handed over to Germany’s shore-bound forces, he suddenly was in a different world—surly armed guards, little food, interrogations, locked doors, bars on the windows. And the train speeding him deeper and deeper into Germany. That’s when he made his move. “He jumped through the window of a rapidly moving train at the imminent risk of death, not only from the nature of the act itself but from the fire of the armed German soldiers who were guarding him,” notes his Medal of Honor citation.

Recaptured, beaten, and thrown into solitary confinement, he would have to wait months for his next best chance at escape—for his ultimately successful bid for freedom as a participant in a mass break-out from a POW camp in October of 1918, just weeks before the Armistice of November 11 ended the war.

Later, after ten years spent as a congressman, he remained in the Washington area and for a time and operated a cattle farm near Gordonsville, Virginia, before he died at age 99 as a resident of Fairfax, Virginia. So came and went a storied hero and outstanding citizen, well worth a quick bow and remembrance even thirty years after his passing on January 17, 1990. Burial, of course, was at Arlington National Cemetery.

- Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

- From “Jimmy Who?” to “What Would Jimmy Do?”

- Washington’s Bold Gamble: Christmas Day 1776

- UVA Club of Pasadena: Cavs Care Gathering at the Raymond

- UVA Club of Boston: UVA Men's Basketball Game Watches

- UVA Club of Richmond: Tour of the Valentine Museum