Thomas Jefferson and “the imported professors” — Part 2

The fact that Thomas Jefferson recruited many of the University of Virginia‘s first faculty members from Britain did not sit well with his critics, as Andrew O’Shaughnessy explains in Part 2 of his article. Mr. O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in UVA’s College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and serves as Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. He is currently writing a book for the University of Virginia Press entitled The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University. He and Jeanie Grant Moore will lead an in-depth exploration of The Old World and the New: Britain and America at Lifetime Learning‘s UVA at Oxford Seminar at Trinity College, University of Oxford from September 14-20, 2019 (sold out).

The fact that Thomas Jefferson recruited many of the University of Virginia‘s first faculty members from Britain did not sit well with his critics, as Andrew O’Shaughnessy explains in Part 2 of his article. Mr. O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in UVA’s College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and serves as Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. He is currently writing a book for the University of Virginia Press entitled The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University. He and Jeanie Grant Moore will lead an in-depth exploration of The Old World and the New: Britain and America at Lifetime Learning‘s UVA at Oxford Seminar at Trinity College, University of Oxford from September 14-20, 2019 (sold out).

Read Part 1 of this article.

Thomas Jefferson and “the imported professors”: “One of the greatest insults the American people have received” — Part 2 (continued from Part 1)

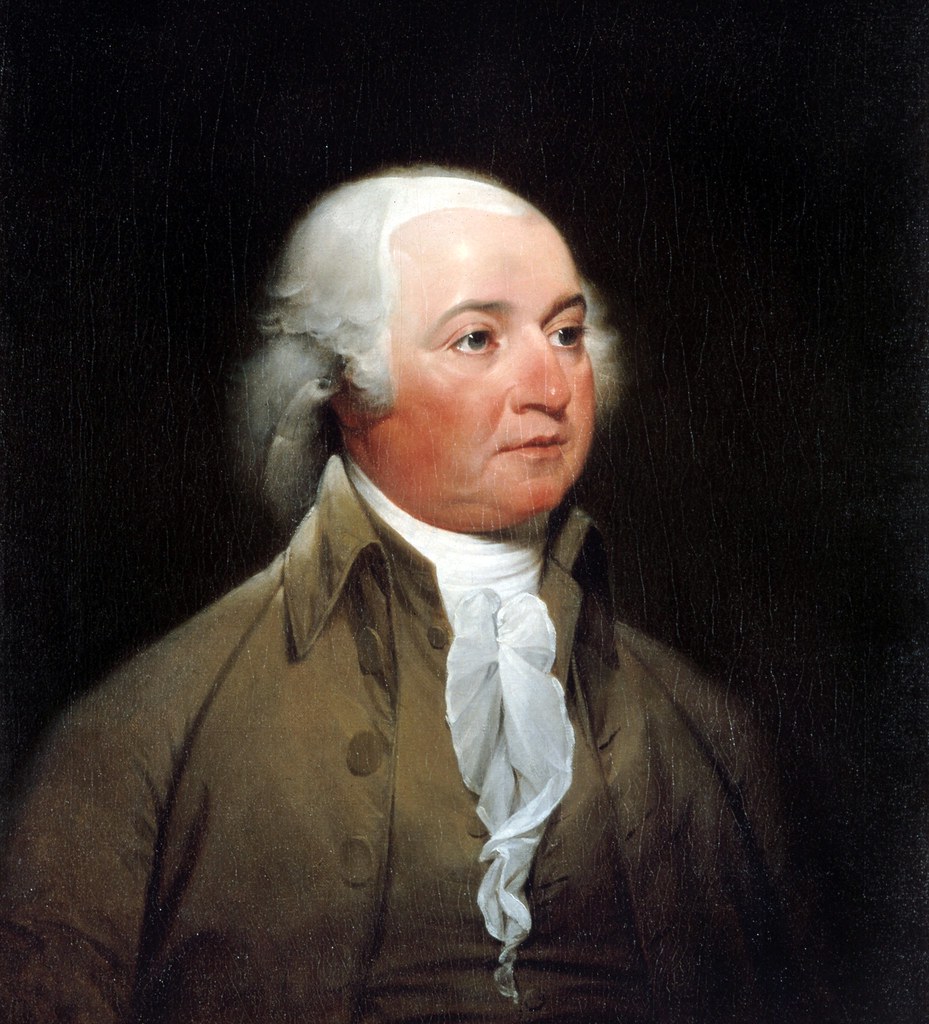

Jefferson had been forced to relinquish an earlier appointment of a professor from England, Dr. Thomas Cooper, a protégé of Joseph Priestley, whose radical views on politics and religion threatened to undermine the support of the state legislature in Richmond. Cooper later became President of the University of South Carolina. Although he tried to appoint the most outstanding faculty member from Harvard University and another professor from Maryland, President Jefferson had written as early as 1800 to Joseph Priestley that he wanted to recruit the best and the brightest from Europe in the first letter describing his ambition for a new University of Virginia. With a preference for native English speakers, he sent Francis Walker Gilmer, whom he regarded as one of the most promising young men of his generation in Virginia, to recruit faculty from England. In 1819, he wrote to John Adams that “our wish is to procure natives where they can be found . . . of the first order of acquirement in their respective lines; but, preferring foreigners of the 1st order to natives of the 2nd order shall certainly have to go, for several of our Professors, to countries with more advanced science.” Adams was unconvinced, writing that:

“I do not approve of your sending to Europe for Tutors, and Professors. I do believe there are sufficient scholars in America to fill your Professorships and Tutorships with more active ingenuity, and independent minds, than you can bring from Europe. The Europeans are all deeply tainted with prejudices both Ecclesiastical, and Temporal which they can never get rid of; they are all infected with Episcopal and Presbyterian Creeds.”

Of the first eight professors, the five recruited in Britain included one German, George Blaettermann. Robley Dunglinson, the Scottish professor of medicine and personal physician to Jefferson, observed that two of three American professors had been born abroad: George Tucker in Bermuda and John P. Emmet in Ireland where his uncle, Robert Emmet, led a rebellion and was executed for treason in 1803.

It was a matter of much criticism that Jefferson had recruited the majority of the professors from Britain. He complained that he had been “squibbed for this” by disappointed applicants in America. There was indignation in the press where articles appeared claiming that he could have found professors at half the trouble and cost in New England or at even shorter distance from Pennsylvania. “Mr. Jefferson,” wrote one, “might as well have said that his taverns and dormitories should not be built with American bricks.” Another article asserted that “This sending of a commission to Europe to engage professors for a new university is, we think, one of the greatest insults the American people have received.” It was likened to taking coals to Newcastle. An article appeared in the Central Gazette in Charlottesville entitled, “Imported Professors.” It quoted northern newspapers “expressing indignation at what they term the “importation of professors,” but it lampooned this sudden abhorrence by “the patriotic editors of New England” for importations from Old England. It reminded their readers that, during the Embargo and Hartford Convention, the northern press “would not only have freely imported professors, but also English legislators, governors and rulers.” It associated their newfound distrust of Britain to their fondness for high tariff duties against British exports to the detriment of Virginia.

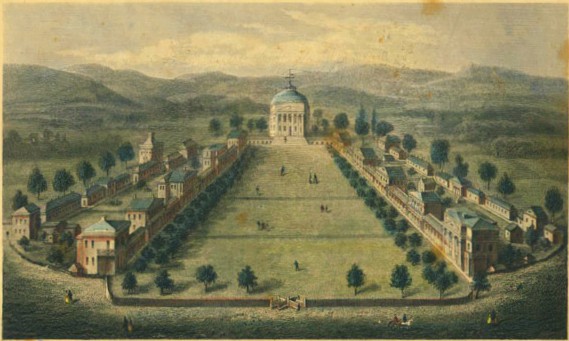

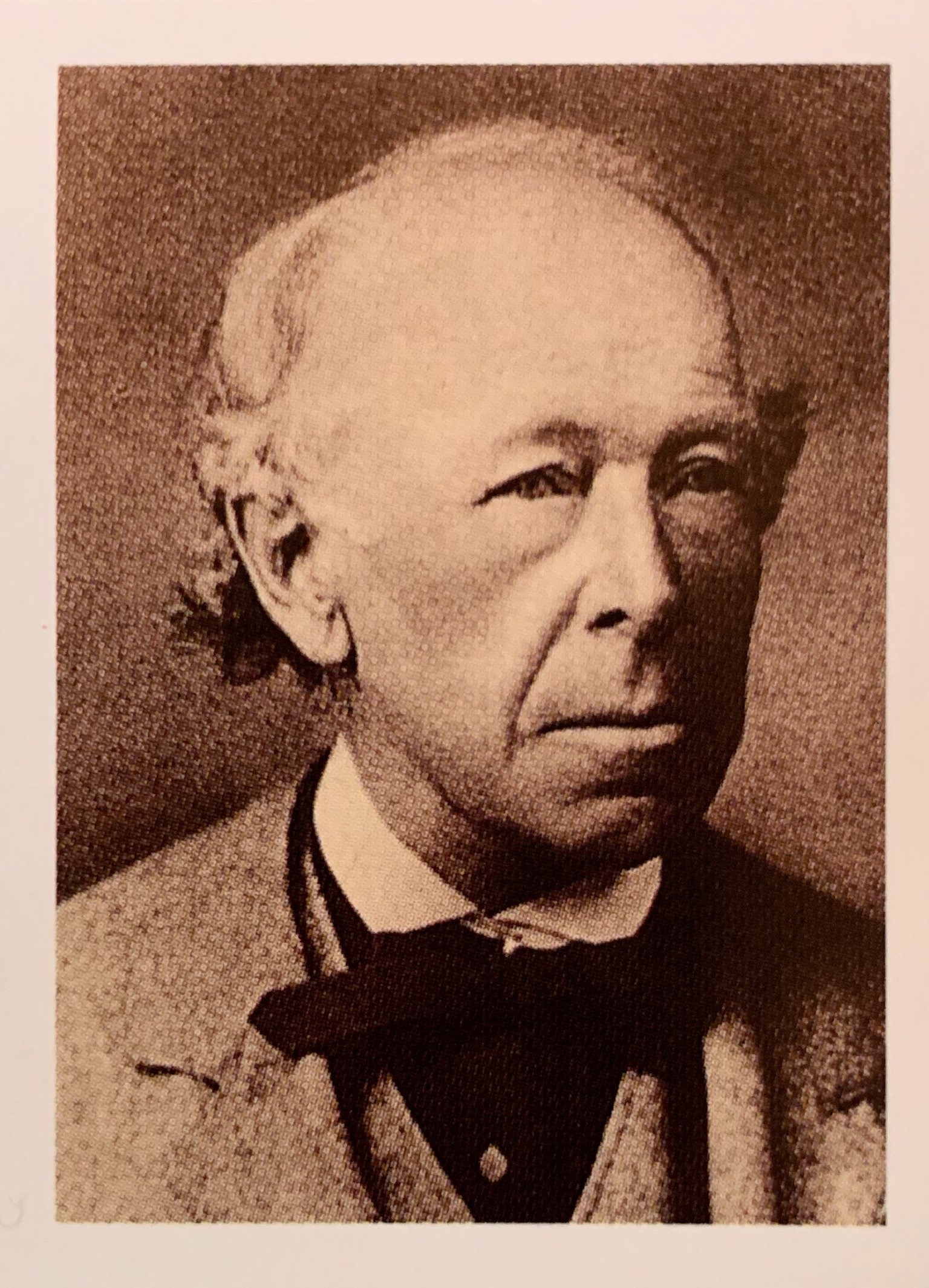

George Long would typify the outstanding first faculty that Jefferson recruited for the University of Virginia. He taught at the university for four years during which he acquired a love of corn bread and married Virginian Harriet Selden, sister-in-law of the Proctor, Arthur S. Brockenbrough, who had helped supervise the building of the “Academical Village.” Long returned to England to become the first professor of Greek at University College which had been established in 1826, based on the radical ideas of Jeremy Bentham and sharing the secular vision of Jefferson for the University of Virginia, as the first university in England outside of Oxford and Cambridge. It later became one of the two founding colleges of London University. Long was a colleague there of Thomas Hewitt Key, the founding professor of mathematics at the University of Virginia, who had been delayed two months on board the “haystack” of the English vessel bound for Norfolk. Key had become professor of Latin at University College in 1828 where he was succeeded by George Long as professor of Latin in 1842.

Long later became a reader in jurisprudence and Civil Law at the Middle Temple. As editor of the Bibliotheca Classic, he produced the first series of scholarly classical translations with English notes to which he contributed his own edition of Cicero’s Orations (1851-1862). As late as the early twentieth century, these were still standard texts in universities when the Encyclopedia Britannica credited Long with having exercised “a wide influence on the teaching of Greek and Latin languages in England.” As a founder and twenty-year member of the Royal Geographical Society, he published an atlas of America and the West Indies and later an Atlas of Classical Geography. Like Jefferson, he became an advocate of public education, resigning his professorship to edit the Quarterly Journal of Education, published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. He was one of its most active members. He edited twenty-nine volumes of the Penny Cyclopaedia and edited Knight’s Political Dictionary. Along with Dr. Thomas Cooper, he was a pioneer in the study of Roman Law and wrote a five-volume history of the Decline of the Roman Empire (1864-1874). Matthew Arnold, the poet and cultural critic, wrote of Long that “his reputation as a scholar is a sufficient guarantee of general fidelity and accuracy of his translation” but that his real gift was engaging his readers and giving life to his subject matter. Long continued to contemplate a return to America and was disappointed not to be able to accept an invitation of the 50th Anniversary of the first class of the University of Virginia, writing “I should be delighted to see the old country again.” His contribution received national recognition when William Gladstone, the British Prime Minister most comparable in intellect to Thomas Jefferson, whom he so much admired, awarded Long with a pension on the Civil List in 1873.

Read Part 1 of this article.

- Bridging the Gap: Understanding Gender Dynamics in Substance Use Disorders Among College Students

- I Feel Like a Speck

- Hello? How Scammers Use AI to Impersonate People and Steal Your Money

- UVA Club of Northwest Arkansas: Spring Happy Hour

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: McCormick Observatory Experience

- UVA Club of Taiwan: Admitted Student Celebration