Thomas Jefferson and “the imported professors” — Part 1

Thomas Jefferson was a bit surprised by the youthfulness of George Long, the University of Virginia‘s first faculty member to arrive on Grounds, according to Andrew O’Shaughnessy. Mr. O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in UVA’s College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and serves as Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. He is currently writing a book for the University of Virginia Press entitled The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University. He and Jeanie Grant Moore will lead an in-depth exploration of The Old World and the New: Britain and America at Lifetime Learning‘s UVA at Oxford Seminar at Trinity College, University of Oxford from September 14-20, 2019 (sold out).

Thomas Jefferson was a bit surprised by the youthfulness of George Long, the University of Virginia‘s first faculty member to arrive on Grounds, according to Andrew O’Shaughnessy. Mr. O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in UVA’s College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and serves as Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. He is currently writing a book for the University of Virginia Press entitled The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University. He and Jeanie Grant Moore will lead an in-depth exploration of The Old World and the New: Britain and America at Lifetime Learning‘s UVA at Oxford Seminar at Trinity College, University of Oxford from September 14-20, 2019 (sold out).

Thomas Jefferson and “the imported professors”: “One of the greatest insults the American people have received” — Part 1 (of 2)

In 1875, George Long wrote from England to one of his former students, Henry Tutwiler in Alabama, recollecting his initial impressions of the University of Virginia in January 1825. As Professor of Ancient Languages, Long had been the first member of faculty to arrive ahead of the opening of the university which he described as being almost uninhabited and looking like an “abandoned city” with all the buildings complete except for the dome of the Rotunda. Long’s correspondent had been a member of the first class of 1825 with Edgar Allen Poe and another Long student called Gessner Harrison who would later hold the chair of his mentor in Ancient Languages. Among a total of eight faculty members, Long was one of five professors who had been recruited in Britain. He felt lonely in the absence of his colleagues and worried that their delayed sailing might harm the prospects of the new university. Embarking on an American ship from Liverpool to New York, he arrived two months ahead of the other professors from Britain who had sailed for Norfolk in an English vessel, described to him “as something like an old haystack: it could just float and go before the wind. During the bitterly cold winter of 1825, he initially lived in solitude without any furniture in the newly constructed Pavilion V.

Long had been apprehensive about accepting a position at the new University of Virginia. He was a Fellow of Trinity College which is still one of the wealthiest and arguably most attractive of the colleges at Cambridge University. He had been a Craven University scholar at Cambridge with his contemporary, the historian Lord Macaulay. He was in difficult financial straits having lost his parents and a substantial plantation in the Caribbean. Although he found it tedious and vexatious, he had reluctantly begun to study law to improve his fortune. He was concerned at the prospect of relocating abroad because of the situation of his family in which he was the guardian to his younger brother and two sisters. He wanted to know whether they would be able to live in the respectable manner to which they were accustomed and whether he would be able to acquire “a little property to advantage.” The salary offer seemed good but he worried about the comparative cost of living. He suspected that food might be cheaper but feared that other articles such, as clothing and furniture, might be dearer “than they are here.” He questioned whether the university had sufficient support to survive or whether it was just an experiment which might fail. He asked: “Is there in the county of Albemarle, or town of Charlottesville, tolerably agreeable society, such as would in some degree compensate for almost the only comfort an Englishman would leave behind him?” He wanted to know whether the teaching demands and vacations would “leave sufficient time… for literary pursuits, and the studies connected with the profession.” He was concerned about tenure and upon what grounds a professor could be removed. He concluded:

“I have no attachment to England as a country; it is a delightful place for a man of rank and property to live in, but I was not born in that enviable station, to which most men here are led to aspire and often in vain. If comfortably settled therefore in America I should never wish to leave it.”

Nevertheless, he admitted that he was conflicted at the thought of leaving his native country and some valuable friends.

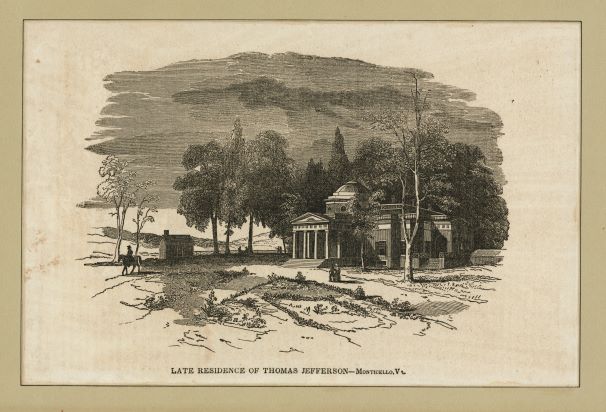

A few days after his arrival in Charlottesville, George Long “walked up to Monticello to see Mr. Jefferson.” Long recollected that he entered the great Entrance Hall where he made himself known to “his servant,” which would almost certainly have been Jefferson’s enslaved valet Burwell Colbert who was the nephew of Sally Hemings. After “a few minutes a tall dignified old man entered” and after looking at him for a moment said, “Are you the new professor of ancient languages?” When the twenty-four-year-old professor answered in the affirmative, Jefferson said, “You are very young,” to which he answered, “I shall grow older,” causing his host to smile and reply, “That was true.” Long thought that the eighty-one-year-old Jefferson “was evidently somewhat startled at my youthful and boyish appearance: and I could plainly see that he was disappointed.” They started to talk and he then stayed to dine with Jefferson at Monticello. Long initially thought his host “was grave and rather cold in his manner, but he was very polite,” simply dressed and “free from all affectation.” Writing fifty years later, on the anniversary of the opening of the university, Long wrote that he remembered “this interview as well as if it took place yesterday.”

During his two months of solitary residence on the Lawn, he made several subsequent visits and occasionally passed the night at Monticello. He was relieved that the founder of the university “became better satisfied with the boy professor” as they talked together “on all subjects.” When he revealed his interest in the geography of his adopted country and “the story of the revolution,” Jefferson “told me much about it, but in a very modest way as to himself.” He showed Long the original draft of the Declaration of Independence. When Jefferson rode on his horse to the university, he generally called upon the boy professor and the two of them would frequently meet over the course of the next year. On one occasion Jefferson spoke about the character of George Washington. Later reading a similar account of Washington written by Jefferson, Long observed that as “a mere writer” he “might have excelled most men of his day.” Long would similarly meet James Madison and James Monroe who were fellow members with Jefferson of the university Board of Visitors. The three of them had laid the foundation stone in 1817. Of Madison, Long wrote, “I think he was one of the most sensible men that I ever spoke to.” He thought Monroe “rather a dull companion,” after sitting next to the former President at dinner during which he said nothing other than asking him, “How is your father?” to which Long replied, “I have no father,” leaving Monroe silent. As to Edgar Allan Poe, Long wrote “I have a faint recollection of the name, but no real remembrance of what he was or what he did at the University.” In the final months of his life, “when his thoughts were always about this new place of education,” Jefferson had been disappointed by unprepared and riotous students but Long wrote that, “he confidently looked forward to the future and to the advantages which that state would derive from the young men who were educated at the University of Virginia.”

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Phoenix: Hoo-liday Party