Babies at the Border: Revisiting the Role of Nurses on Ellis Island

Nursing has historic ties to U.S. immigration policy, and Arlene W. Keeling provides commentary on how nurses should still play a critical role at our southern border. Ms. Keeling, PhD, RN, FAAN is the Centennial Distinguished Professor Emerita in the School of Nursing and former director of the Eleanor Crowder Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry at the University of Virginia. She is the current president of the American Association for the History of Nursing (aahn.org).

Nursing has historic ties to U.S. immigration policy, and Arlene W. Keeling provides commentary on how nurses should still play a critical role at our southern border. Ms. Keeling, PhD, RN, FAAN is the Centennial Distinguished Professor Emerita in the School of Nursing and former director of the Eleanor Crowder Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry at the University of Virginia. She is the current president of the American Association for the History of Nursing (aahn.org).

For several years now, the nation’s attention has been repeatedly drawn to “the immigration problem” on the southern borders of the United States. Last summer, news reports about babies screaming for their mothers as families were separated and photos of teens and young children peering through chain-linked fences tugged at our heartstrings and furthered divided an already divided America. Crowds chanting “build the wall” were juxtaposed with images of demonstrators demanding justice for families fleeing violence to seek asylum in the United States.

More recently, the issue of immigration has repeatedly taken center stage. Each time it does, my thoughts turn to my current research on the nurses of Ellis Island, and I wonder why there are not large contingents of nurses at the border. They are certainly not evident in news reports.

On Ellis Island, nurses employed by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) worked in “a middle place,” balancing the needs of newly arrived families with their public health role as state agents charged with upholding the laws of the land. It is a complicated story. We are a nation of immigrants, many of whom came to America seeking religious freedom, economic opportunity, or freedom from political persecution. Our history is replete with conflicting immigration policies. There was the exclusion of the Chinese, prejudice against those of Irish and Italian descent, and the deportation of those who were seen as “unfit” physically or mentally to enter the country. There were also, however, decrees from the U.S. President that all immigrants be treated with respect.

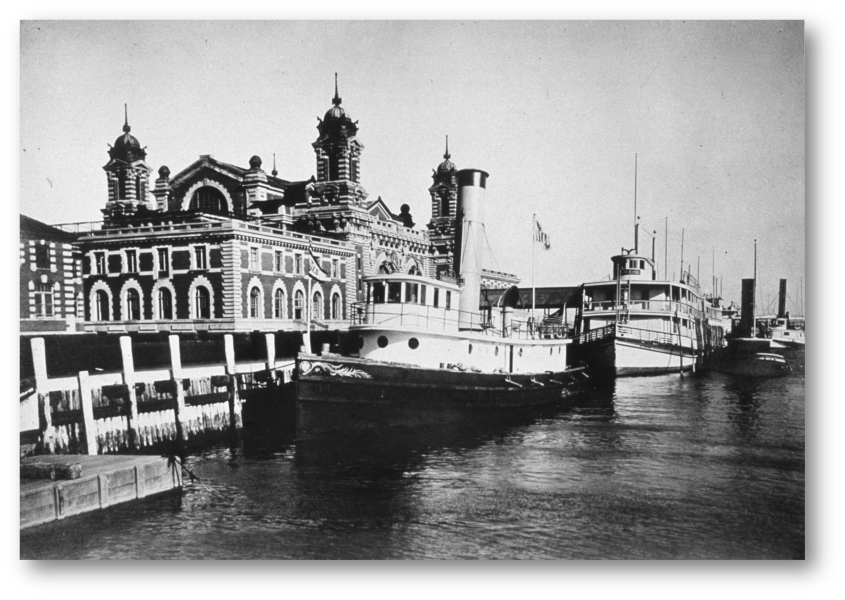

More than a century ago in the federal immigration station on Ellis Island, U.S. Public Health Service nurses were essential players in the systematic process of screening and caring for European immigrants. In 1913, there were more than 25 nurses, both male and female, employed in the sprawling government hospitals on the Island. These nurses bathed babies, fed children, cared for those who were sick, assisted in surgeries, and comforted little ones whose mothers were quarantined. It was a huge undertaking: thousands passed through the Great Hall every day. As one immigrant described the scene: “They got off the boat and then they walked…up those stairs into the building… And they looked pretty bad” (Lorie Conway, Forgotten Ellis Island). Few immigrants spoke English. Between 1880 and 1924, 23.5 million immigrants arrived in the United States, largely from countries in southern and Eastern Europe but also in smaller numbers from China, Japan, Mexico, and Canada (D. Rossner, Hives of Sickness).

The immigration station on Ellis Island needed strong leadership, and President Theodore Roosevelt appointed attorney William Williams as commissioner. Williams insisted on compassion and respect, writing in his first directive: “Immigrants shall be treated with kindness and civility by everyone at Ellis Island. Neither harsh language nor rough handling will be tolerated.”

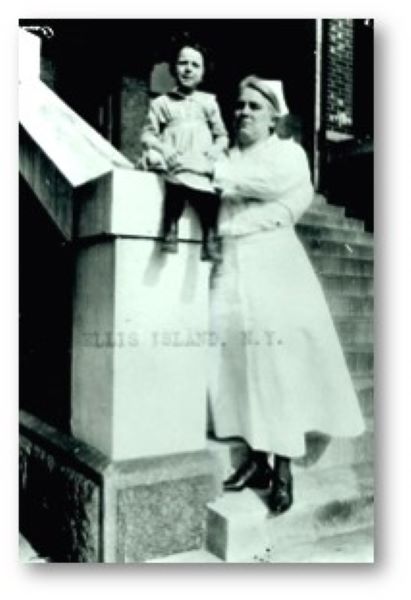

On Ellis Island, nurses gave compassionate care to the youngest immigrants. Children with contagious diseases such as measles, scarlet fever, trachoma, ringworm, mumps, and chicken pox encountered nurses in first the General Hospital, and later in a special Contagion Hospital. Elizabeth Martin, a Hungarian immigrant, recalled her experience as a child: “The nurses, the ladies in white, we used to call them. They were very nice. They talked to the children. They stroked their hair, and they touched their cheeks and held our hands” (Conway, Forgotten Ellis Island).

According to one physician: “There were quite a number of babies involved and one became attached to them even if you couldn’t speak their language! It was not necessary… all that was necessary was gentle and kind treatment” (Dr. Grover Kempf, USPHS, 1912). In 1904, the New York Times reported much the same, noting: “There are usually from six to twelve children in the Ellis Island Hospital. As a rule, they are stunted in growth and bear traces of unwholesome nurture, but they pick up under the skillful treatment of doctors and nurses, and the breezes from a beautiful harbor bring a tinge of color into their wan faces.”

While much has changed in immigration policy since the turn of the 20th century, some things remain the same. Most importantly, there is a need for compassionate care for immigrants, especially when they are seeking political asylum or fleeing violence. There is also a desperate need for immigration reform, now caught up in our nation’s politics. Examining our past makes it clear that nurses had a critical role to play in the processing of arriving immigrants. Today, we can only hope that among those ordered to the border there is a significant contingent of military nurses.

For more on this topic, see Keeling, Hehman, and Kirchgessner: History of Professional Nursing in the United States: Toward a Culture of Health (Springer, 2018).

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Houston: Hoo-liday Party

- UVA Club of Fredericksburg: Hoo-liday Lights Tour