1968: Ball of Confusion

Written by Larry Sabato, Director, UVA Center for Politics

Reposted with permission from Sabato’s Crystal Ball

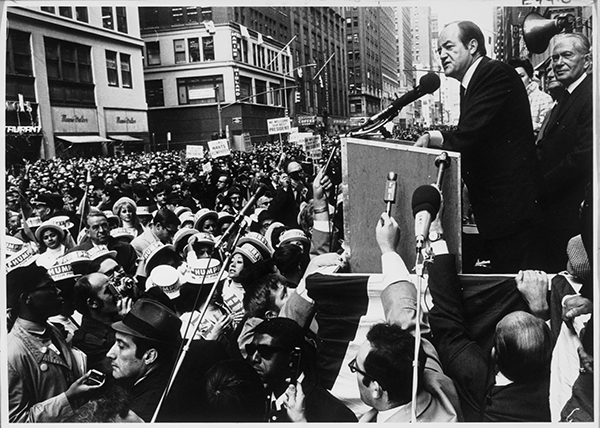

The UVA Center for Politics’ latest documentary, Ball of Confusion, has begun airing on PBS stations across the nation this week. Check your local listings to see when it’s playing in your area, and click on the image below to watch the trailer. The documentary recounts the three-way presidential contest among Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, and George Wallace held against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and civil unrest at home. That election, decided 47 years ago today, remains amongst the most extraordinary in American history, as Larry J. Sabato writes below.

— Sabato’s Crystal Ball Editors

If you lived through 1968, you can’t forget it — even if you want to.

It was the worst of times, a year from hell, marked by savage warfare in Vietnam, political assassinations, urban riots, and militancy of all sorts. People talked seriously about whether the United States would hold together.

“Ball of Confusion,” a popular song written and produced by Norman Whitfield for Motown Records (and made famous by The Temptations), captured the exhausting, puzzling tenor of the era:

“Ball of confusion. That’s what the world is today…

The cities ablaze in the summer time…

Evolution, revolution, gun control, sound of soul.

Shooting rockets to the moon, kids growing up too soon…

Where the world’s headed, nobody knows…

Fear in the air, tension everywhere…

Eve of destruction…People all over the world are shouting, ‘End the war.’”

All presidential election years are chaotic by nature, but from the start, 1968’s conditions were ominous. President Lyndon B. Johnson, elected by the largest popular-vote landslide in modern history in 1964, was deeply unpopular as he tried to prevail in Vietnam — a war he had escalated on a massive scale.

Nonetheless, as the year dawned, no one believed Johnson would voluntarily give up the office he had long craved and the power he enjoyed exercising as much or more than any of his predecessors. Yet events took hold and convinced even LBJ that, at best, he could only win another term narrowly and only after further dividing the country.

For years, Johnson and his lieutenants had been proclaiming there was a “light at the end of the tunnel” in Vietnam. After four long years of war, the president had committed an astounding 536,000 troops to the conflict. Extensive bombing of North Vietnam, the country was told, had weakened the enemy and would drive the Communists to the peace table.

And then came Jan. 30, 1968, when North Vietnamese troops and their allied Viet Cong launched a massive assault in over 100 locations throughout South Vietnam. It was timed for the Tet lunar new-year holiday, and was called the Tet Offensive. Even though militarily, the attacks were repulsed by U.S. and South Vietnamese troops, and the Communists suffered heavy losses, the shock of this widespread well-coordinated effort belied the claims that the war was all but won.

An Associated Press reporter took an iconic photograph during the offensive on Feb. 1. General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, South Vietnam’s chief of national police, executed a handcuffed prisoner who was a suspected Viet Cong. It was wartime, of course, but the visual brutality caught on film stirred anti-war sentiments in the United States.

CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite went to Vietnam and delivered a devastating on-air assessment: “To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion.” LBJ and his advisers understood the implications; they had lost middle-class America — and whatever credibility remained in their pronouncements of impending victory.

Meanwhile, Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-MN) had entered the race for president with a vigorous anti-war message, backed by legions of well-mannered “Clean for Gene” college students campaigning in New Hampshire and elsewhere. On primary night, March 12, Johnson’s forces were shocked by the president’s relatively narrow 49.6% to 41.9% victory over McCarthy. Yes, LBJ was a write-in candidate — a stance sometime taken by incumbents who wished to seem above the fray. However, there was no denying that the results were closer than expected.

Just four days later, an even more formidable foe, LBJ’s longtime antagonist Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY), launched his White House bid. The McCarthy campaign was enraged by “ruthless Bobby” and his attempt to interrupt McCarthy’s momentum, yet unlike McCarthy, RFK was a front-running contender who might have been able to beat Johnson (though that was far from certain at a boss-controlled convention) and win the general election against his brother John F. Kennedy’s old foe, Richard Nixon.

Robert Kennedy’s campaign had barely begun when President Johnson threw in the towel. On March 31, at the end of a televised national address on Vietnam, LBJ stunned the nation and the world as he intoned, “I shall not seek, nor will I accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

Johnson insisted he had made the sacrifice in order to pursue peace full-time, and privately he reminded supporters that the males in his family died young. (LBJ was correct, and he died at the age of 64 — just four years and two days after he departed the White House.) Still, there was no denying that if the Vietnam War had been going well, Johnson would likely have sought reelection.

Kennedy and McCarthy began contesting the primaries, and RFK won the lion’s share. In 1968, though, the system was far different than today. There were only 15 primaries, and some were already claimed by so-called “favorite sons” or slates of unpledged delegates that kept their states above the fray until the convention.

While Kennedy and McCarthy shadow-boxed their way across the country, LBJ’s logical successor, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, went to work behind the scenes to claim the prize and did not enter a single primary. The August national party convention in Chicago would be run not by delegates elected in primaries but by party bosses such as the Windy City’s longtime Mayor Richard J. Daley, Sr.

The nomination campaign was interrupted twice by tragedy. On April 4, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was gunned down on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, TN, where he had been supporting black sanitation workers in their strike for higher wages and better conditions. James Earl Ray was apprehended two months later in England and convicted of the assassination. While he was apparently the lone gunman, suspicions remain to this day that Ray was backed financially by others.

Martin Luther King was just 39 years old. While more militant civil rights groups were starting to eclipse him, King was the Nobel Peace Prize-winning apostle of non-violence whose leadership was irreplaceable. Americans of all stripes were deeply shaken, and unfortunately the shock turned to violence in many communities. Widespread rioting occurred in dozens of urban areas across the United States.

In the cauldron that was 1968, violence seemed to breed violence. Robert Kennedy thought he had a reasonable chance to capture the nomination, especially after a crucial victory over McCarthy in California on June 4. A triumphant RFK shouted to the surging crowd at Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel, “Now it’s on to Chicago and let’s win there!”

Those were the last public words spoken by Robert Francis Kennedy. Leaving the scene through a pantry behind the stage, Kennedy was shot in the head by Palestinian supporter Sirhan B. Sirhan. Just 42 years old and the father of 10 children — with an 11th on the way — Kennedy died on June 6. Americans could not believe that the nightmare of Nov. 22, 1963 had returned. Yet another Kennedy had been struck down by bullets in the prime of life. The nation mourned as the heartbreaking rituals of death played out on television. RFK was laid to rest near JFK in Arlington National Cemetery.

By this point, most people were somewhere between despair and depression. Nonetheless, one American saw opportunity for redemption in the midst of misery: Richard Milhous Nixon.

Most political observers had long since written off Nixon. Following his close defeat for president in 1960, Nixon lost decisively for governor of California in 1962. Right after that election, Nixon held his “last press conference” in which he said to the reporters he hated, “Just think about what you’ll be missing. You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore!” Adding insult to injury, ABC News aired a TV special entitled, “The Political Obituary of Richard M. Nixon.”

Nixon’s resurrection began in earnest during the 1966 midterm elections, when he traveled constantly to campaign for any Republican on the ballot. The GOP picked up 47 U.S. House seats and many other offices, and Nixon had earned a fistful of political chits. The disaster of Vietnam was just as responsible for Nixon’s rise. Even his enemies admitted that former Vice President Nixon had broad experience in, and understanding of, foreign policy, thanks to his international travels during President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration.

Nixon knew he would never be beloved or win an election on personality points. Instead, if America was ready for a president who could extricate us from Vietnam and skillfully pursue foreign policy, then Nixon fit the bill.

From New Hampshire onwards, Nixon had marched through the primaries, winning all of the important contested ones. However, Nixon still had many in his own party who doubted his electability. The more liberal Republicans rallied to New York Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller, but the real threat came from the new California governor, Ronald Reagan. Nixon smartly conceded the Golden State primary to Reagan; even though Nixon was from the state, too, he might well have lost to Reagan or had a close call.

When the Republicans gathered in Miami Beach during the week of Aug. 5, they smelled victory and didn’t want to make a mistake by choosing the wrong ticket. Reagan might actually have won the nomination if the South had backed him, but Nixon forged a “Southern strategy” with U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond from South Carolina. It was understood that Nixon would appoint conservative Supreme Court justices and stress “law and order” issues favored by whites. Nixon, who had received about 30% of the votes of African Americans in 1960, all but conceded the black vote to the Democrats in exchange for critical white votes.

Nixon easily won the GOP nomination on the first ballot, and selected the nearly unknown new governor of Maryland, Spiro “Ted” Agnew, as his running-mate. Agnew had been for Rockefeller but had not alienated Nixon, and factional leaders in the GOP vetoed more prominent vice presidential candidates. At the time, Agnew offended no one — though this pick would soon come back to haunt Nixon in the campaign and again, years later, when the Watergate scandal was destroying his presidency. (In 1973 Agnew was shown to have taken bribes. He pled no contest to a charge of tax evasion and was forced to resign the vice presidency.)

The relative calm of the Republican convention gave way to a storm never seen before or since. Democrats gathered in Chicago in late August. So did many thousands of anti-war demonstrators determined to “Dump the Hump.”

Even though LBJ did not make an appearance at the convention, he and his political lieutenants controlled a majority of delegates. President Johnson was determined to make Humphrey toe the line on Vietnam and prod the delegates to approve a platform supportive of the administration’s war. Mayor Daley kept the convention in his iron grip, and tried to do the same outside on the streets.

Remarkably, especially given his emphatic withdrawal only a few months earlier, Johnson harbored some last-minute hopes that he could swoop into Chicago and be re-nominated. The convention had long since been scheduled around Johnson’s birthday, in what would have been a glowing tribute to his first five years in the White House and the prospect of four more. Instead, it would have been very difficult for the Secret Service and local police forces even to guarantee Johnson’s safety in Chicago. LBJ’s pipedream dissipated quickly.

With the strong backing of traditional party leaders and constituencies, it was relatively easy for Humphrey to defeat McCarthy and a late entry, Sen. George McGovern (D-SD) (who claimed he was a waystation for grieving RFK delegates). HHH picked Sen. Edmund Muskie of Maine as his running-mate. The moderate former governor would prove to be the most liked candidate on either ticket, a useful contrast to Agnew.

However, the public barely noticed Humphrey’s acceptance address because of the mayhem in the host city. Chicago was convulsed with large-scale riots and police beatings of demonstrators. The smell of tear gas was everywhere, even in the convention hall, where Daley “thugs” — the word used by CBS anchor Cronkite — hustled allegedly unruly reporters and delegates right out of the building.

The Chicago meltdown sent HHH into the fall but also the polling basement. Post-convention Labor Day surveys had Humphrey trailing Nixon by more than 20 percentage points. Amazingly, it looked as though Nixon couldn’t lose.

Yet there was a complicating candidate that made the election both deeply divisive and thoroughly unpredictable. His name was George C. Wallace, former governor of Alabama, whose inaugural catchphrase, “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” encapsulated and encouraged white anger. Wallace’s approach was populist, and he told voters to “send them a message” about busing to achieve desegregation, rising crime, and anti-Americanism.

Running as the nominee of his own “American Independent Party,” Wallace generated his strongest appeal in the South, but also in blue-collar white precincts throughout the country. He was hurting Nixon disproportionately, especially in the Deep South, a reality that dogged the Republicans throughout the fall. Wallace knew he couldn’t win the election, but he hoped to secure enough electoral votes to throw the choice of the next president to the U.S. House of Representatives — where he could play the broker, influencing the policies of the next administration.

Wallace chose retired Gen. Curtis LeMay as his running mate in an attempt to project toughness in foreign policy. LeMay turned out to be a bit too tough for many of Wallace’s own supporters, because the military man was an advocate of the use of nuclear weapons in Vietnam and elsewhere.

For Humphrey and the Democrats, Wallace made the election winnable because he would not have to come close to 50% of the vote in order to prevail. The Nixon campaign understood this well, and promoted the idea that “a vote for Wallace is a vote for Humphrey.”

Nixon hoped to ride out the fall with his big opening lead; he didn’t rock the boat and stressed international experience with his TV slogan, “This time, vote like your whole world depended on it.” Underlying it all was the belief that voters would punish the incumbent party for Vietnam and elect a Republican who promised “peace with honor.”

Democrats capitalized on Ed Muskie’s public appeal by focusing their fire on Spiro Agnew, who made a number of embarrassing gaffes, such as declining to visit more urban ghettoes with the comment, “If you’ve seen one city slum, you’ve seen them all.” Arguably the most successful TV ad of the campaign was the soundtrack of laughter as viewers saw an “Agnew for Vice President” placard. The narrator concluded: “This would be funny if it weren’t so serious.”

Vice presidential candidates aren’t enough to win or lose most elections. Humphrey’s basic problem was that he needed to break with LBJ’s war policy in order to energize liberals — but Johnson insisted on obeisance. At last, still trailing and desperate, HHH gave a speech on Sept. 30 in which he argued for a ceasefire and an end to the bombing of North Vietnam. The response from anti-war Democrats was positive and polls began to tighten.

President Johnson had his own October surprise in store, an Oct. 31 address to the nation in which he announced the bombing halt of North Vietnam and a promising initiative to start peace talks with the Communists. The Nixon camp had long feared such a stratagem, and Nixon’s agents — and the candidate himself — had been using a go-between, Anna Chennault, to urge the South Vietnamese president not to agree to peace talks and instead to hold out for a better deal under a President Nixon.

Thanks to wiretaps and other surveillance, LBJ was well aware of Nixon’s actions, which the infuriated president regarded as treasonous. Without revealing his sources, Johnson let Nixon know directly that he expected his cooperation on his peace initiative. Humphrey was aware of Nixon’s efforts, but chose not to use the issue because the polls were essentially tied and he believed he would win. Employing an incendiary last-minute charge might have backfired.

Nixon gathered his immediate family and warned them that he could lose again, and they should prepare themselves. Indeed, for much of a long Nov. 5 election night, Nixon’s high command feared a repeat of 1960 and, at times, thought its candidate was headed for defeat.

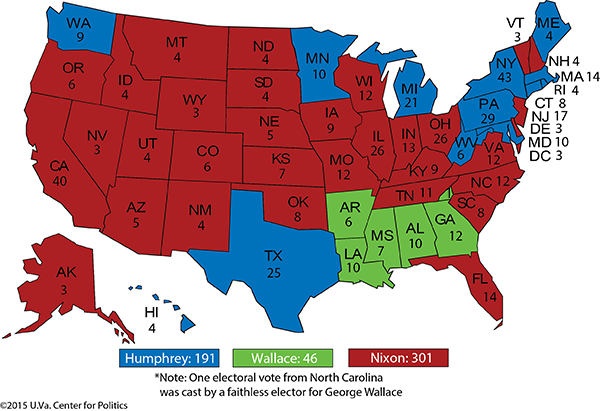

Early the next morning, though, Illinois — one of the states that gave JFK his victory, with Mayor Daley’s help — fell into Nixon’s column by a tiny margin. The nationwide popular vote was a dead heat, with Nixon edging Humphrey by about 500,000 votes, 43.4% to 42.7%. In the all-important Electoral College, Nixon’s advantage was a substantial 301 to Humphrey’s 191. George Wallace had secured 13.5% of the vote and amassed 46 electoral votes by carrying Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi (Wallace’s 46th vote came from a so-called “faithless elector” in North Carolina who ignored the Tar Heel State’s choice of Nixon).

With a weak mandate and a thin plurality, President-elect Nixon faced daunting obstacles as he assembled his governing team. Sure enough, LBJ’s peace efforts fell apart — and the Vietnam War would grind on for another four years. Vietnam had claimed one president already, and eventually it would help to bring down Nixon too. Much of the foundation of the Watergate scandal that would force Nixon’s resignation in 1974 could be traced to efforts to surveil, contain, and disrupt the anti-war movement.

As a truly tragic year came to an end, there was far more apprehension than hope throughout America. And then came a Christmas miracle. In December, NASA launched a manned mission, Apollo 8, to achieve the first circumnavigation of the Moon. This amazing feat was highlighted on Christmas Eve, as the three astronauts, Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders, read portions of Genesis to a wide-eyed, worldwide audience on Earth.

The first photograph ever taken of “Earthrise” from Moon orbit reminded all people of our tiny, fragile place in the universe. From almost every part of the globe came a fervent wish: Maybe, just maybe, human beings would recognize the need for peaceful efforts to preserve our shared planet.

There was hope for a better future after all, as cursed 1968 receded into history.

- Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

- From “Jimmy Who?” to “What Would Jimmy Do?”

- Washington’s Bold Gamble: Christmas Day 1776

- Increasing Your Impact With Planned Giving

- UVA Club of Boston: UVA Men's Basketball Game Watches

- UVA Club of New Mexico: Cavs Care - Roadrunner Food Bank