The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint

We cannot understand Leonardo da Vinci unless we see that he was a scientist all through his career, argues Francesca Fiorani in her new book, The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint. Fiorani lectured on da Vinci at a Lifetime Learning recorded event in April 2021 and provides answers to audience questions below. Fiorani is a professor of art history in the Department of Art in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

We cannot understand Leonardo da Vinci unless we see that he was a scientist all through his career, argues Francesca Fiorani in her new book, The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint. Fiorani lectured on da Vinci at a Lifetime Learning recorded event in April 2021 and provides answers to audience questions below. Fiorani is a professor of art history in the Department of Art in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia.

The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint

Were the techniques (types of tempera, oil, or fresco) used to restore Leonardo’s paintings in recent years the same as they were used by the artist then, or are the ones used today better for the longevity of the restored art?

Today conservators recommend the use of traditional materials for the restoration of Leonardo’s works—and of Renaissance artworks in general. These traditional materials are usually more compatible than modern materials with the structure of the original painting and thus limit possible undesirable reactions that can occur between materials of different composition. But conservators also recommend that these traditional materials be applied in such a way that they can be distinguished easily from the original paint. For instance, retouching and repainting, which are often needed for damaged works and which, for instance, were used extensively in Leonardo’s Last Supper, should be invisible from a distance so that an artwork can be appreciated aesthetically in its entirety; but at close range, these additions should be easily discernible from the original so that one can evaluate exactly the original work of the master. In other words, restorations attempt to return an artwork to its original undamaged appearance, while at the same time trying to delay the inevitable decay of the materials of which the work is made.

In this respect, the recent restorations of Leonardo’s Adoration of the Magi or his Virgin and Child with Saint Anne are exemplary: the consolidation of lifting paint flakes, the strengthening of wood supports, the clearing of old and yellowing varnishes, and the revarnishing of the entire work were all actions that restorers took on these paintings. But they did not overpaint damaged areas, as was the standard practice in previous decades, because they wanted to distinguish their work from the original—and they also wanted to make sure that it could be corrected if unexpected reactions occur later. In fact, today restorers value a great deal the reversibility of their interventions; they wish not to alter permanently an original artwork. This is also why they document their interventions extensively with photographs and written reports and, in the process, provided invaluable new knowledge on Leonardo’s painting technique, including his famous smoky effects, or sfumato.

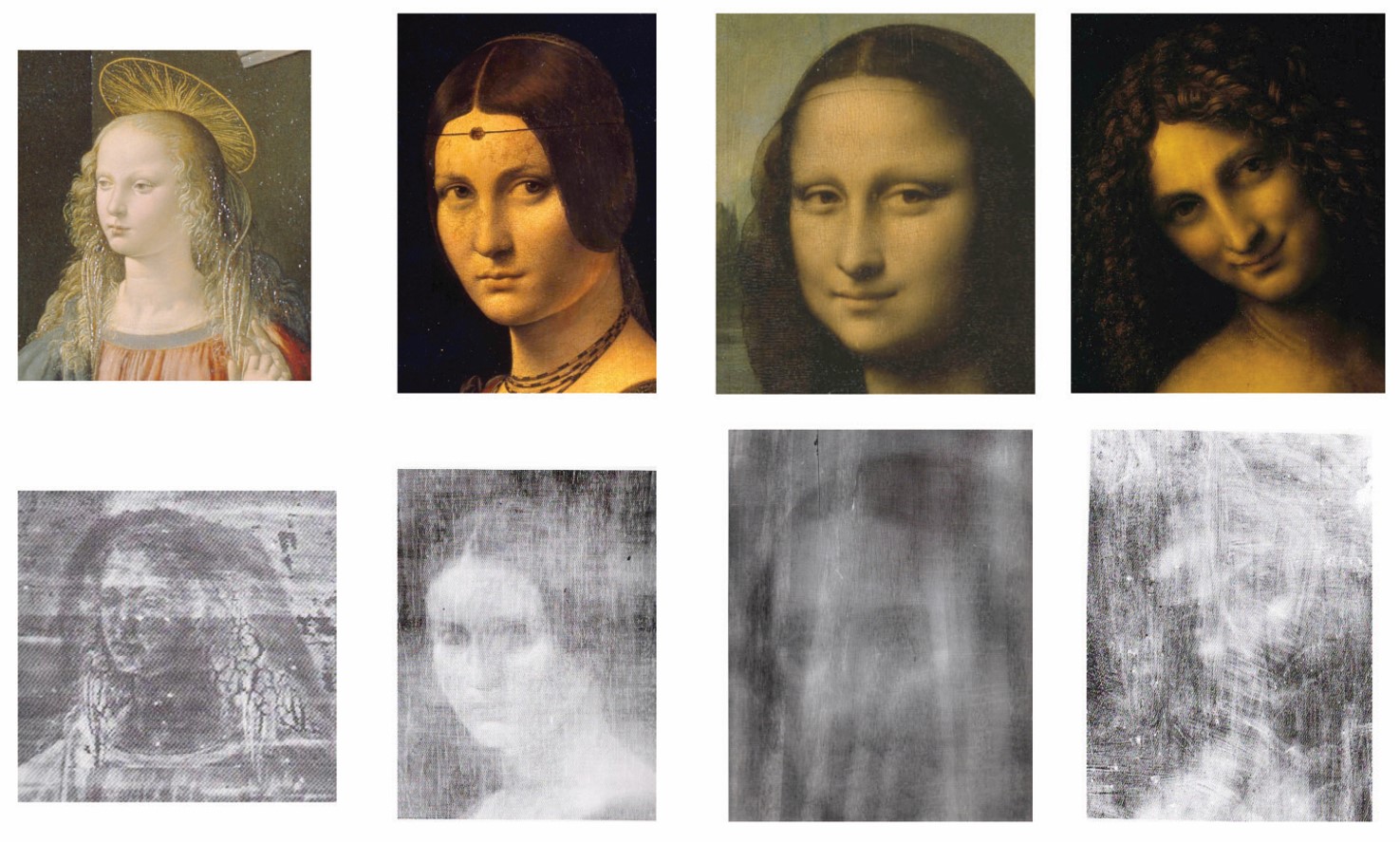

How were the four black and white images created that appeared below the four painted images of women in the final slide?

This image shows details of faces from four paintings by Leonardo and their corresponding X-ray images, which are informative on the different colors Leonardo used to paint human faces. What the X-ray images show is that Leonardo made figures less and less distinguishable from their backgrounds. For the face of the Virgin in his early Annunciation, he used colors that contained large amounts of lead white (in the X-rays the lead white corresponds to the dark areas). But for later works, such as the Mona Lisa and Saint John the Baptist, he preferred highly diluted colors that contained a minimal quantity of lead white, which he applied in multiple, thin layers. He found that these highly diluted colors, which are also very malleable, were best suited to capture minimal variations of light and shadows on people’s faces, which in turn indicated more nuanced shifts in people’s emotions. Here is a visual explanation of Leonardo’s technique to achieve his famous smoky effects and, with it, reach to the psychological depth of his figures.

Did Thomas Jefferson study Leonardo’s notebooks?

It is unlikely that Thomas Jefferson knew Leonardo’s original notebooks as most were kept in private collections in Italy. Those in England were in the possession of King George III, who kept them in his library in Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace), but it is doubtful that during his visit in the spring of 1786 Jefferson had the chance to see them. Jefferson did meet the king in an official visit, but the king was far from welcoming to the man who had written the Declaration of Independence from England.

But Jefferson was familiar with Leonardo’s art. He owned an English translation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting, which had been printed in London in 1721. The book was in Jefferson’s library from the 1770s to 1815, when Jefferson sold it to Congress together with many other of his books. The exact copy that Jefferson owned is lost but Special Collections, University of Virginia Library owns another copy of the same edition, which you can find here. I studied this copy for my website on Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting.

In addition, Jefferson owned a painting representing Saint John the Baptist, which was a copy of Leonardo’s painting representing the same subject. It hung in the main hall at Monticello and although Jefferson’s painting is lost, we know how it looked, as Jefferson himself described it in detail in an inventory of the art works he kept in his house. Here are Jefferson’s words: “John Baptist, a bust of natural size, the right hand pointing to heaven, the left, deeply shaded, is scarcely seen pressing his breast, which is covered by his hair flowing thickly over it. It is seen almost in full face. On canvas, copied from Leonardo da Vinci.” Jefferson’s inventory from which this painting’s description is taken is also kept at Special Collections, University of Virginia Library and you can see here.

Can you give more recommendations for books and online resources that people can research about Leonardo?

Many great books and digital resources have been published on Leonardo and it is difficult to select just a few. But here are some that I am especially fond of because they are highly informative but also very approachable: they make Leonardo’s writings, drawings, and paintings come to life for both experts and non-experts. Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing by Martin Clayton, Head of Prints and Drawings for Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle, which holds the largest selection of Leonardo’s drawings, is an enlightening explanation of how Leonardo sketched. Leslie A. Geddes’s Watermarks: Leonardo da Vinci and the Mastery of Nature is a captivating study of how Leonardo looked at water from the point of view of hydraulics, engineering, art, and philosophy. If you wish to understand better Leonardo’s training with his master in Florence, the exhibition catalogue edited by Andrew Butterfield, Verrocchio, Sculptor and Painter of Renaissance Florence, is the best place to start.

As for Leonardo’s notebooks, they are best discovered on the website e-Leo, an amazing digital resource that allows users to turn the pages of all of Leonardo’s notebooks—and read his words too (only in Italian). If you are interested in restoration, the book by Marco Ciatti and Cecilia Frosinini, Il restauro dell’Adorazione dei Magi di Leonardo. La riscoperta di un capolavoro, is a must; even if you don’t read Italian, you’d want to look at this book because the restoration photos are simply stunning. And if, after you read all those books and played around on the e-Leo website, you wish to dive deeper into Leonardo, Carmen Bambach’s four-volume Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered is the book for you.

Continue your education with Lifetime Learning’s online resources available to alumni, parents, and friends.

The Thoughts From the Lawn (TFTL) blog is published by Lifetime Learning at the University of Virginia’s (UVA) Office of Engagement. This platform features UVA faculty and staff articles for the benefit of UVA’s alumni, parents, and friends. The views expressed in TFTL blog posts reflect the views of the authors and not those of Lifetime Learning. Lifetime Learning reviews the content and links in each article before publication; however, we take no responsibility for inaccurate information and/or links that lead to post-publication, unintended sites. Lifetime Learning is not responsible and will not be held liable for blog comments and reserves the right to remove malicious or mean-spirited responses.

- Behold – The Art of Giving a Compliment

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Men's ACC Basketball Tournament - UVA Fan Events

- UVA Northern Virginia Programs Fair

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication