The First Attack on Charleston’s AME Church

(Reprinted with permission by Maurie McInnis)

In 1822, white residents burned the predecessor to today’s church, fearing an insurrection by the city’s black majority.

By Maurie McInnis, U.Va Vice Provost for Academic Affairs; Professor of Art History and author of Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade.

In the dark of night, a white man entered the AME church in Charleston, South Carolina, and opened fire. Nine people were killed.

In the dark of night, a white man entered the AME church in Charleston and started a fire. The structure was completely consumed and the church destroyed.

One is a headline from 2015, the other from 1822. The shooting this week has evoked horror and outrage across the nation; the event 200 years ago provoked only satisfaction among the city’s white inhabitants. Charleston, the wealthiest city in pre–Civil War America, was also the city with the largest percentage of residents of African descent, greater than 50 percent in every census until 1860. It has a long history of racialized violence and of violence inflicted against the black church. The shooting this week at the African Methodist Episcopal Church is another bloody chapter in that long history.

The fire in 1822 destroyed a small wooden church located a few blocks away from the present structure affectionately called “Mother Emanuel.” The church had been founded in 1818 by Morris Brown, a member of Charleston’s small free black population (nearly 1,500 in 1820). Charleston was then a city of 25,000 (more than 12,000 of whom were enslaved), and it is estimated that several thousand African Americans joined the church in the early years. On the corner of Reid and Hanover streets, this earlier church was in an area called Charleston Neck, just north of the city boundary then on Calhoun Street, where today’s AME church stands. The early congregants had chosen this location in part because it was not in the city limits, and thus stood outside the close scrutiny of the city’s authorities.

The authority to whip people of African descent, with little or no due process, was an important element of the slave regime.

Being away from the watchful eye of the authorities was important because that watchful eye was often a harassing one. The most systematic and visible form of racial control in Charleston was the City Guard. Founded in 1783 as one of the first acts of the newly created City Council after American independence, the city’s police force was created to control what was the largest enslaved population in an American city. It was given authority over a wide range of behaviors, both black and white. From the beginning, however, black and white residents were treated differently: The police could “inflict corporal punishment, by whipping, on persons of color.”

The authority to whip and physically punish people of African descent, with little or no due process, was an important element of the slave regime. We know well that many slave owners used physical punishment and the threat thereof to control the people they owned, but such violence also had state sanction, regulations that were only to increase as the decades passed. As one visitor noted, they “know and they dread the slaveholder’s power.” With the church being in Charleston Neck, however, it meant that the City Guard did not regularly patrol there, which gave its members some degree of freedom in their worship.

The primary concern of the police was to guard against servile insurrection. And as a white population living among an enslaved majority, they had reason to fear. In addition to the police force, they established a curfew for African Americans. Every night curfew was announced by the tolling of the bells of St. Michael’s and the beating of drums for a quarter-hour. After “drum beat,” the City Guard patrolled the streets, arresting black Charlestonians out after curfew. Visitors often noted that the city felt as if it were under constant threat. When landscape architect and journalist Frederick Law Olmsted visited Charleston, he noted that when curfew rang, the city felt like a “military garrison,” under a “general siege.”

Charleston’s City Guard arrested people of color for many reasons, most of them mere excuses to harass and intimidate: being on the streets without a pass after the ringing of the bells; not wearing a slave badge (if required); participating in merriment; smoking a cigar; hollering; selling goods in the market without a pass; or gathering in groups of greater than seven. These are just a few of the supposed offences specified in the city’s ordinances.

The city’s pervasive fear of servile unrest was confirmed one day in May 1822 when an enslaved man named Peter Desverneys told his owner what he had heard about plans for a slave uprising. The city authorities jumped into action (or overreaction), arresting men and confining them in the city’s Work House, the notorious institution for the punishment and incarceration of people of color. The City Guard was on high alert for weeks, patrolling its streets in greater numbers and with enhanced vigilance.

The city, under the leadership of Mayor James Hamilton Jr., convened a court and initiated proceedings. The testimony that emerged, most of it coerced through violence and threats of hangings, only heightened the city’s fears. A white resident told a friend elsewhere that during those weeks, “no one, not even children ventured to retire” and that the “the passing of every patrol and every slight noise excited attention.”

A free black man named Denmark Vesey was fingered as the leading organizer. Born into slavery in the Caribbean, Vesey had purchased his freedom in 1799 with the proceeds from a lottery. Though named by several of the accused, Vesey himself never spoke to the court. He was not allowed to face his accusers. He did not admit guilt. Nevertheless, he was condemned to execution by hanging. On July 2, Vesey and five other men were carried in wagons from the Work House to a site in Charleston Neck called “the Lines.” There they swung from trees, “their bodies … delivered to the surgeon for dissection, if requested,” according to the newspaper announcement. It was a site carefully crafted to send fear throughout the African American community. More hangings followed later in the month.

Eventually more than 131 men were arrested, 35 were hung, and 43 were ordered to leave the state or the country. In August of that year, the court proceedings were published. This document, voraciously read and consumed by all in the city, told a story that deviated somewhat from the surviving court transcripts. It seemed calculated to frighten the city’s slaveholding elite, emphasizing certain parts of the testimony more than others. One of the principal points emphasized was that many of the men involved in the plot were the “indulged and trusted” domestic servants who were intimately connected with their slave-owning families. Now every Charlestonian was looking at the people they owned and wondering, What if?

The City Guard arrested people of color for many reasons: participating in merriment; smoking a cigar; hollering.

The other chilling fact for many Charlestonians was the supposed role of religion, especially the “African Church,” as they called it then. According to the printed testimony, Vesey was “considered the Champion in the African church business. … [I]t is generally received opinion that this church commenced this awful business.” Of those arrested, 19 were members of the AME church. Rolla Bennett, one of the men eventually hanged who belonged to the then-governor of South Carolina, Thomas Bennett, supposedly told the court that Vesey “was the first to rise up and speak, and he read to us from the Bible, how the Children of Israel were delivered out of Egypt from bondage.” Preaching a liberation theology, Vesey supposedly met with enslaved men in the city, convincing them to work with him in plotting the takeover of the city’s armories, and commencing a massacre of all the whites, “not permitting a white soul to escape.”

Today historians disagree on the extent of the planning for the insurrection. Did Vesey and his men have a plan for as many as 9,000 men ready to attack the city from the countryside? Or was there merely talk of freedom and liberty that was then exaggerated by the city’s leaders in order to spread fear? Or is the answer somewhere in between?

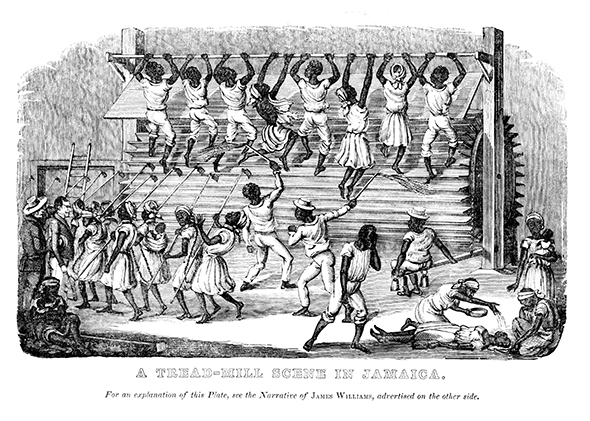

Though we may never know for certain if the plot was real, the fear aroused was very real. The outcome of that fear was an increase in violence and intimidation aimed at the city’s enslaved residents. These actions took many forms. For example, in 1822, Charleston passed the Negro Seaman Act and incarcerated all free black sailors who entered Charleston until the time of embarkation, on account of their race alone. In 1825, Charleston started construction on a massive building called the Arsenal (later home to the Citadel), to fortify the city with weapons in preparation against insurrection. That same year, the city added a new form of punishment to the Work House: the treadmill. The enslaved were forced to walk for eight hours a day, three minutes on and three minutes off. Perhaps most shocking of the Work House’s provisions was that a master could send the people he owned to the Work House, where, for a fee, they would be “corrected by whipping,” confined to a cell, or forced to walk on the treadmill. No proof of wrongdoing was required. A master could do this on a whim. No questions were asked.

The city’s white leadership also saw to it that the African Church was burned. Not long afterward, the city outlawed all black churches. The enslaved were not allowed to meet for worship without a white person in attendance.

The church has always been a symbol of black community and of resilience in the face of racism, violence, and hatred. It has also been a frequent target of racial hatred. Throughout American history, burning and bombing churches has been used as a way to intimidate. (For more on the history of violence against black churches, read Slate essays by Matthew J. Cressler and Kadida E. Williams.) After the Vesey insurrection scare, one Charlestonian wrote that “some plan must be adopted to subdue them.” That sounds chillingly like what Dylann Storm Roof, the alleged shooter in this week’s attack, supposedly said: “I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over our country, and you have to go.”

It appears that Roof may have driven from near Columbia, South Carolina, to Charleston. It therefore seems likely that he chose this church for its historic and symbolic importance. Located in the heart of the city, just off Marion Square, only a few hundred yards from the Arsenal built to protect the city against servile insurrection, it stands there defiant: a historic AME congregation in a beautiful, soaring building of an architectural style and grandeur reminiscent of many of the city’s white churches. The church is proud of its history. Just under the steps leading to the church’s front door is a sculptural monument to Denmark Vesey. It shows the faces of young children, supposedly listening to his preaching. Erected after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, their eager young faces speak to the promise of liberty that Vesey supposedly fought for and that the post–Civil Rights era supposedly promised. Now the faces of those young children, and the entire nation, are streaked with tears as we realize how deeply rooted racial violence and hatred remain in the heart of at least one young man who walked into the AME church in Charleston and opened fire.

There was no justice for Denmark Vesey and the others who were executed and banished in 1822. There was no justice for the members of the AME church when their building was burned. There was no justice for the millions of African Americans who were wrongly held in bondage. Justice in this case will not merely be a guilty verdict for the accused shooter. Justice demands that we acknowledge and address our nation’s continuing racial prejudice and disparities. Justice demands that we address police brutality, mass incarceration, and the lack of equal access to opportunity for millions of black Americans. The shooting is not simply the action of one deranged and evil individual, but instead springs from our nation’s long history of racial prejudice and violence against black Americans.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Charleston shooting.

Maurie McInnis is a professor of art history at the University of Virginia and author of Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade.

- UVA Club of Baltimore: Monthly Virtual UVA Committee Meetings

- UVA Football Weekend Tailgates 2024

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Kids in Crisis Holiday Clothing Drive