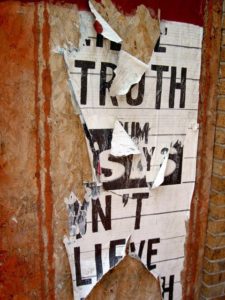

Finding truth

Written by Jeb Livingood, Assistant Professor of English; Associate Director of the UVA Creative Writing Program, College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences

I served as a reservist in the Coast Guard for twenty-four years, and I’ve been teaching English at UVA for eighteen. Those are two different worlds—the military and academia—and I often joke that I’ve never quite fit in either. To my UVA English colleagues, I’m the conservative military guy. In the Coast Guard, I was always the wacky academic liberal. I could never win. My military specialty was in intelligence, which must seem like an odd choice for an English professor. But the reality is that intelligence analysis and academic work have a lot in common.

There’s a Thomas Jefferson quotation chiseled over a New Cabell Hall doorway: “For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.” That’s a pretty good mission statement for UVA, whether we’re researching new ways to treat cancer in the medical center or whether we’re arguing about what the grandmother really means when she cries, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children!” at the end of Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” We’re chasing after the truth. It’s what we do here.

That’s what the Intelligence Community (IC) tries to do too. The IC’s seventeen members—the CIA, the FBI, the NSA, all the rest (and yes, even the Coast Guard), are not fundamentally about spies and covert action and missions impossible. That’s the movies. In real life, the IC spends most of its time gathering and grinding through information and trying to provide decision makers with the best possible assessment of where the truth lies. Or, as I tell students in a college advising class (COLA) I teach on intelligence analysis, the IC at least tries to reduce a decision maker’s doubt enough that they can actually make a decision. In fact, that’s most succinct definition I can give my students for what “intelligence” is: it’s information that reduces doubt.

On the one hand, I’d say we could all use a little doubt reduction these days. We’re drowning in a sea of information, 24/7, and it’s getting harder and harder to know what is real and what is not. But honestly, what worries me more is that far too many of us, both liberal and conservative, seem far too sure about far too much. We know what the truth is, and we don’t like to challenge it, myself included. And worse, we live in an information-based world where we can increasingly pick and choose our sources, and where we can shelter our ingrained biases. No one likes to question, must less change their beliefs, their internal narratives. After all, doing so means having to rewire your brain—literally. It hurts. It takes time.

Which, I try to tell my COLA students, is part of what your years in Charlottesville are for. Learn how to gather up the confounding and conflicting evidence that lies before you. Devise ways to organize it. Identify gaps. Do more research. And give extra time and special attention to findings that challenge your beliefs: those annoying outliers are sometimes the golden nuggets that can change your thinking.

Jefferson didn’t use a big T for “truth” in his letter to William Roscoe; he used a little t. Because when someone decides what the truth is in advance, they can always go find evidence to support it. I suspect Jefferson understood that basic human tendency—and saw some of that stubborn blindness in himself—even without Google, Siri, and Alexa to tell him it was there.

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Women's ACC Basketball Tournament - UVA Fan Events

- UVA Northern Virginia Programs Fair

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication