Twin Monsters

In recognition of the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Lifetime Learning is re-posting the October 2015 article “Twin Monsters” by Susan Tyler Hitchcock. Hitchcock (GSAS ’78), author of Frankenstein: A Cultural History (Norton, 2007), was formerly a faculty member in the University of Virginia‘s School of Engineering and Applied Science. She is currently a senior book editor at National Geographic.

In recognition of the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Lifetime Learning is re-posting the October 2015 article “Twin Monsters” by Susan Tyler Hitchcock. Hitchcock (GSAS ’78), author of Frankenstein: A Cultural History (Norton, 2007), was formerly a faculty member in the University of Virginia‘s School of Engineering and Applied Science. She is currently a senior book editor at National Geographic.

TWIN MONSTERS

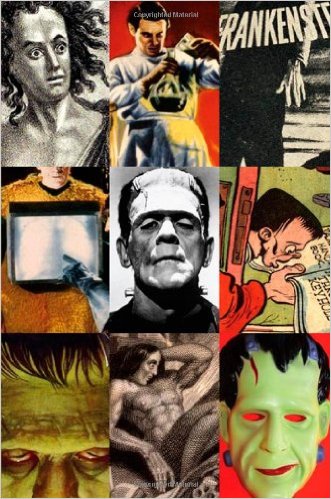

It’s the time of year to think about monsters. Two of the most iconic monsters of our time, Dracula and the Frankenstein monster, spring from one remarkable confluence of personalities, imagination, and weather.

It’s June 1816 in Geneva, Switzerland. Historians have come to call 1816 “the year without a summer,” one of the first instances when a local weather event was recognized to have global effects. The year before, Indonesia’s Mount Tamboro had erupted with tremendous force, spewing ash into the atmosphere so thick and long lasting that it screened out the sun, brought near-freezing temperatures to Europe and North America even in midsummer, and severely damaged food harvests all year round.

It also caused strange, electrifying, and violent weather, the backdrop against which a band of young English renegades read ghost stories together and challenged one another to write their own.

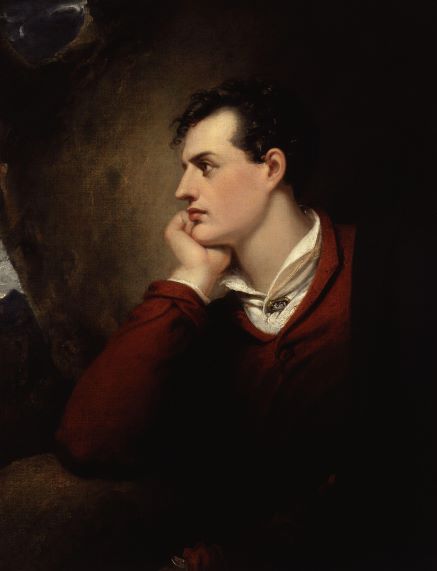

George Gordon, Lord Byron, was the group’s ringleader. His sojourn in Geneva represented the start of an exile from his home country that was to last the rest of his life. Leaving behind a wife and daughter, a half-sister with whom he was rumored to have had an affair, and a reputation as an immensely popular poet, Byron was also famously “mad, bad, and dangerous” yet ever so appealing in his dark and brooding way. He had thought in leaving London that he might rid himself of his recent fling, 18-year-old Claire Clairmont, but she pursued him across the Continent, accompanied by two others: her stepsister, Mary Godwin, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had fallen passionately in love with Mary, despite his wife and two children at home. Rounding out the scandalous circle was John Polidori, a young doctor who answered Byron’s apothecary needs in exchange for the chance to be close to such a celebrity.

As the story goes, one stormy night Byron proposed that each of them write a tale designed to thrill and terrify. Ultimately only two of the five met the challenge.

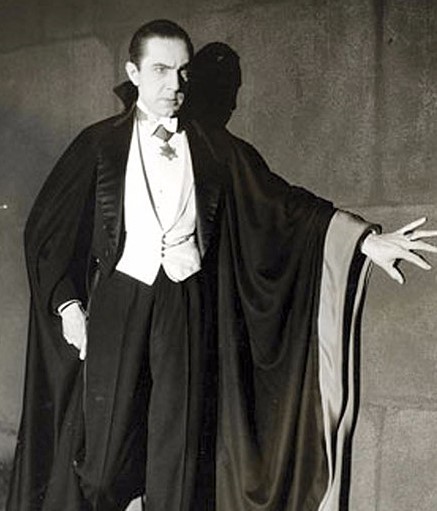

Byron burst forth with the seeds of a story, but it was Polidori who ultimately wrote it down. The story, titled “The Vampyre,” told of a pair of young men. The one, wide-eyed and innocent, was slowly overtaken by the other, a shadowy and demonic character ultimately identified as a “vampyre”: an immortal who thrives by sucking the life out of his victims. Published in 1819, the story is said to have inspired the most famous English vampire novel, Dracula, written by Bram Stoker nearly 80 years later.

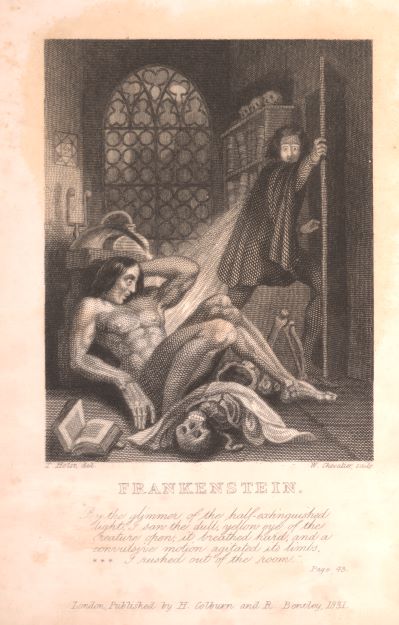

It took her several restless days and nights, but Mary Godwin was the other one of the five whose imagination gave birth to a horror story. It presented itself like a dream vision. “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together,” she recounted later. “I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” Her story took shape and became the novel that has sparked hundreds of retellings: Frankenstein.

What an odd set of twins to have been born out of the same moment of creation, two myths of horror, a dichotomy of worldviews. The Dracula myth, conveying a dark view of a world in which the evil inhuman nature will never die; and the Frankenstein myth, which holds out the slightest glimmer of hope that we might learn not to shun the monsters we have created but instead to embrace them, discovering some innate goodness deep within.

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Livestream: A Conversation with Dr. Cornel West & Dr. Robert P. George

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: Hoos Reading Hoos January Book Club