Coastal Ocean Water Quality

In recognition of Earth Day on April 22, we highlight Scott Doney‘s research on coastal nutrient pollution and its impact on the marine ecosystem. Mr. Doney is the Joe D. and Helen J. Kington Professor in Environmental Change, Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Virginia.

In recognition of Earth Day on April 22, we highlight Scott Doney‘s research on coastal nutrient pollution and its impact on the marine ecosystem. Mr. Doney is the Joe D. and Helen J. Kington Professor in Environmental Change, Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Virginia.

People are drawn to ocean shores to live, to work, and to play. Nearly half the population of our country resides in coastal counties in cities large and small, rural communities, and vacation destinations. Coastlines also support especially rich and diverse biological habitats, such the many wetlands and estuaries that abound along the Atlantic shoreline. In fact, much of what we value about the coast – opportunities for recreation and fishing, the natural beauty and scenery – depends on healthy ecosystems. The question then is how can people and nature coexist sustainably along our coasts?

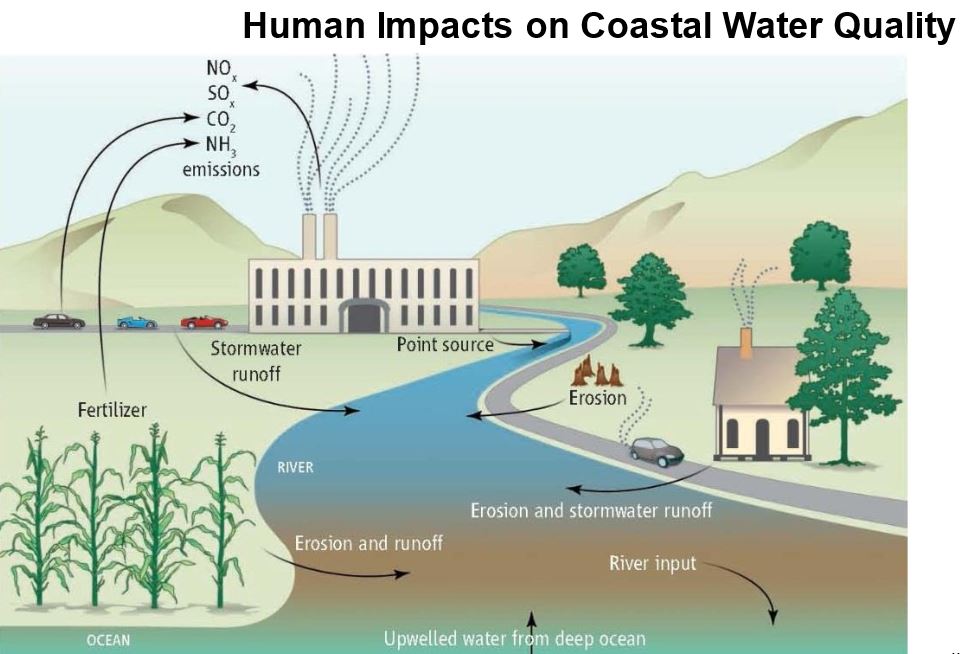

I had the opportunity to explore this topic with students last month at the UVA–National Geographic on Campus event hosted by the pan-university Environmental Resilience Institute. I focused on a well-known problem, nutrient pollution that leads to algal blooms and low oxygen in estuaries and coastal bays. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers, agriculture, sewage, and atmospheric pollution make its way into rivers and groundwater and eventually to the sea. We have made considerable progress to solving aspects of this problem through improved farming techniques, more judicious use of lawn fertilizers, upgraded wastewater treatment plants, and pollution controls on power plants.

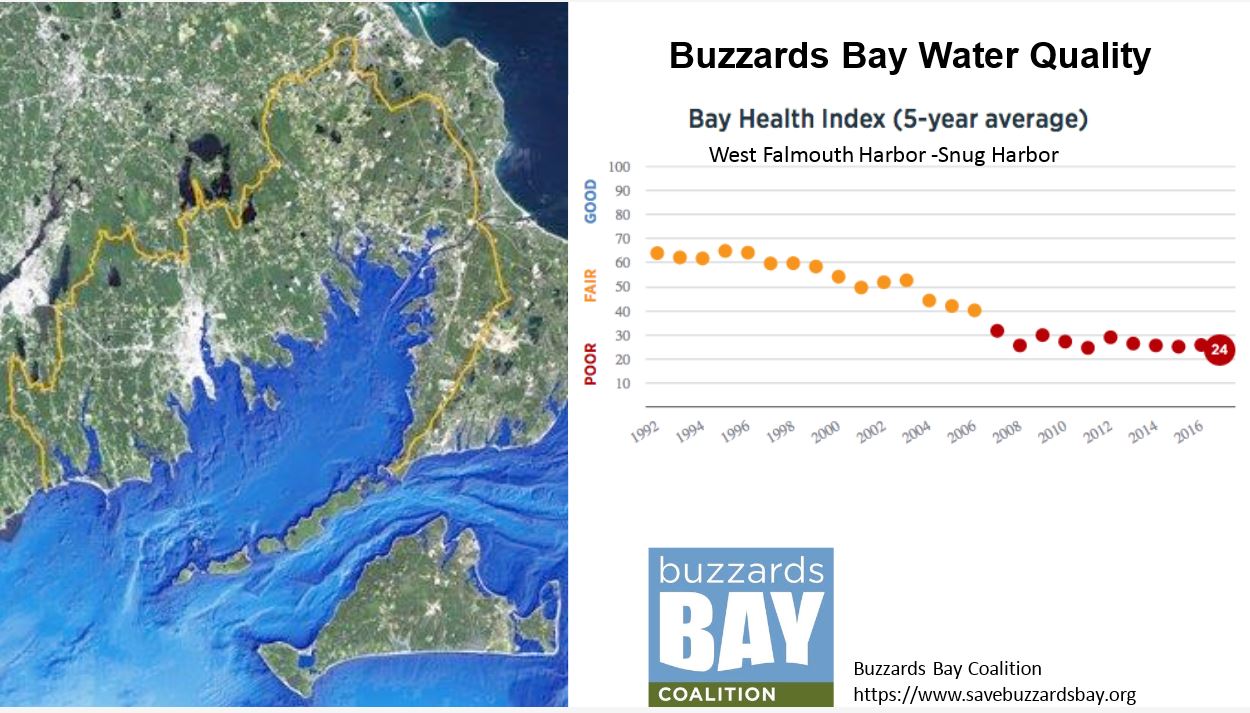

For the past five years, I have been studying coastal nutrient pollution, impacts on the marine ecosystem, and possible solutions for Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, which is close to my former New England home before I moved to UVA. What makes it such a great study site is our partnership with a local citizen science organization, the Buzzards Bay Coalition, who have collected water quality data at roughly a hundred sites around the bay for several decades. This historical data record allows us to track nutrient pollution and ecological damage over time and to frame new experiments.

What we found is striking and somewhat puzzling. Efforts to reduce nutrient pollution sources to the bay are working. Locally, many homes in the bay’s watershed have been moved from household septic systems, that release nitrogen to groundwater, to wastewater treatment plants that are increasingly using advanced methods to remove nitrogen before discharging into coastal waters. Community education and town-level action has focused on improving river and groundwater quality. Regional and national regulations such as the federal Clean Air Act are cleaning up our atmosphere and lowering nitrogen deposition downwind.

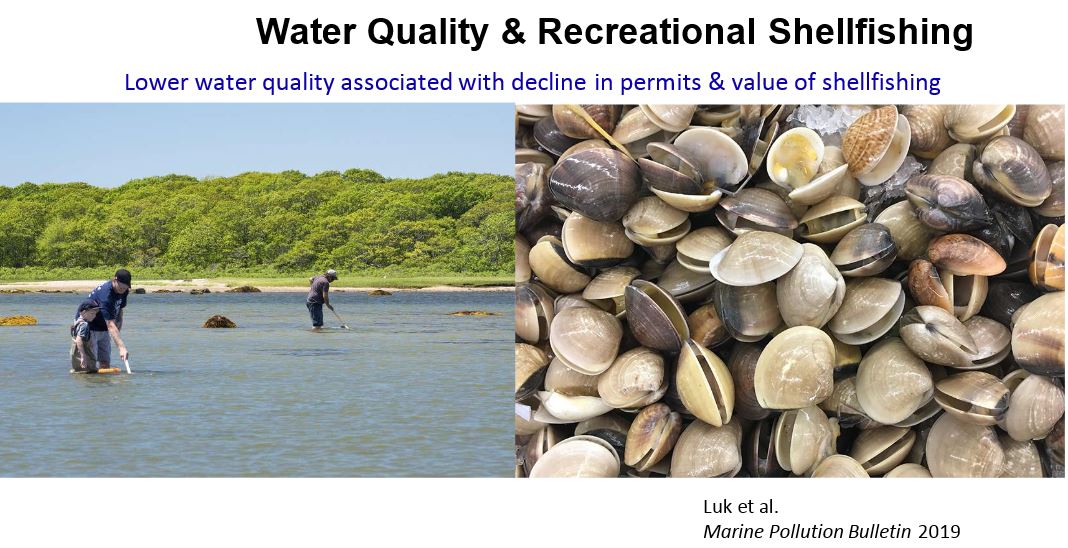

Despite these great strides, summer algal blooms in Buzzards Bay are still growing with time. The culprit may be climate change. Ocean warming and elevated precipitation in New England may be enhancing the amount of nitrogen making it from the land to the sea and exacerbating coastal algal blooms because plankton grow faster in warmer waters. When the blooms collapse, the organic carbon in the plankton are respired by microbes that release carbon dioxide and consume oxygen. Nutrient pollution thus drives coastal acidification and hypoxia (low-oxygen conditions) that threaten nearshore fish and shellfish stocks and aquaculture. We found that degraded water quality in the bay is also linked to less demand for recreational shellfishing, a valuable part of the local economy.

More algae in the water column reduces water clarity and the amount of light reaching seagrass beds growing in shallow waters of the bay. Seagrasses are vital components of coastal ecosystems, creating food and habitat for many fish and invertebrates and storing large amounts of so-called blue carbon in the sediments. To better observe water clarity in the future, we developed new remote sensing tools that utilize satellite imagery and aerial drones to map bloom conditions.

Many of the science lessons learned from Buzzards Bay are applicable broadly to other coastal waters in Virginia and up and down the Atlantic coast. UVA has a rich history of coastal science, much of the work leveraging the facilities and water access provided by UVA’s Anheuser-Busch Coastal Research Center on the Virginia’s eastern shore. I am continuing to research coastal chemistry, climate, and ecosystem questions but now through the Virginia Coast Reserve Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) science program led out of UVA’s Department of Environmental Sciences.

- Life at the Top: Climate Change in Utqiaġvik, Alaska

- The Only Thing We Have to Fear is Fear Itself

- Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

- UVA Club of Tidewater: Hoos at Harbor Park

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Cavs Care - Volunteer Income Tax Assistance Events

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: Hoos Reading Hoos Book Club