Madison’s Role in the Founding of the University of Virginia

James Madison was a key friend and advisor to Thomas Jefferson as plans for the University of Virginia were developed, and he remained involved in the project after Jefferson’s death. Jim Todd, Assistant Professor in UVA’s Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, gives us an interesting look at Madison’s contributions to the University’s founding.

James Madison was a key friend and advisor to Thomas Jefferson as plans for the University of Virginia were developed, and he remained involved in the project after Jefferson’s death. Jim Todd, Assistant Professor in UVA’s Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, gives us an interesting look at Madison’s contributions to the University’s founding.

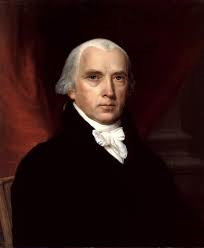

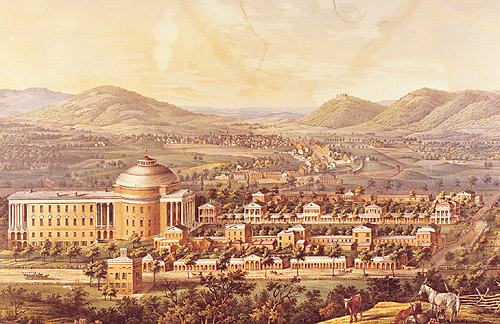

Those fully familiar with the life and contributions of James Madison find it hard to understand why Madison is not given more recognition than he is. Without him, it is very questionable as to whether the Constitutional Convention would have happened, let alone be as successful as it was, and, without him, we might not have had a Bill of Rights added to our Constitution. It may be an overreach to claim that, without him, we would not have the University of Virginia, but he played a much more important role in the founding of our university than is generally recognized. The role he played, at least until Jefferson’s death, was a subordinate one, the key friend and advisor to whom Jefferson turned over and over for advice and critiques of his plans and the one who was present at almost all of the important meetings that led to the successful founding of the University and its location in Charlottesville.

Perhaps some of the neglect of Madison is due to the lack of general appreciation for how close he and Jefferson were. Their friendship was not based simply on the extraordinary political partnership they had shared for so many years. They were both sons of the Enlightenment, with exceptionally wide-ranging interests. They shared the problems of running a large estate and owning a large number of slaves. They especially shared an interest in all aspects of farming. Jefferson once called Madison “the best farmer in the world” with “the greatest agricultural knowledge of any man [Jefferson] knew,” strong praise coming from someone who might have been eligible for that title himself.

There is, of course, no way to know when Madison and Jefferson first discussed Jefferson’s ideas about a public university, which Jefferson scholars think he was considering as early as 1779. But we do have the letters that passed between Jefferson and Madison, and they provide strong evidence of Madison’s role. Madison himself had advocated the formation of a national university, as had each president before him, but Congress had not acted. James Norton Smith, the editor of Republic of Letters, the remarkable three-volume collection of the Madison-Jefferson correspondence, notes that as Madison’s second term as president neared its end, “The Sage of Monticello was anxious to have the Sage of Montpelier back in the neighborhood because [he] had already staked out a significant retirement project for them: the creation of the University of Virginia.”

Madison was intimately involved in the realization of that project, and, when Jefferson had to step down as rector in 1826, the year of his death, it was Madison who took over for him until his failing health forced him to step down in 1836, the year of his own death. It seems to me that Mr. Jefferson would want his friend’s contribution to the University recognized and appreciated considerably more than it is. Madison Hall, which opened in 1905 as a YMCA and now houses the University’s Office of the President, is of course named in honor of Madison, but there is no statue of Madison anywhere on Grounds. Washington, who had no association with the University, has one, facing the Lawn just south of Pavilion VIII. Why not one for Madison, who, on visits to the University as a frail old man, could be seen being helped down the Lawn by his younger wife Dolley?

There is a wonderful statue of the two of them in front of the visitor’s center at their home, Montpelier, with James sitting down and holding a book and Dolley standing behind him with her hand on his shoulder. A good start to providing Madison more recognition at UVA would be to have a copy of that statue placed in front of Madison Hall, facing across the street to the statue of Mr. Jefferson that stands in front of the Rotunda. I can’t guarantee it, but I think Mr. Jefferson would smile more broadly were that to happen.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party