Stay on Track: Turning Resolutions into Results

Sarah Memmi is Assistant Professor of Commerce in the McIntire School of Commerce at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on the psychology of consumer behavior. In particular, she studies the relationship between goal pursuit and personal resources (e.g., time, money, energy). Memmi’s work has been published in outlets including the Journal of Consumer Research and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Sarah Memmi is Assistant Professor of Commerce in the McIntire School of Commerce at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on the psychology of consumer behavior. In particular, she studies the relationship between goal pursuit and personal resources (e.g., time, money, energy). Memmi’s work has been published in outlets including the Journal of Consumer Research and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

On Christmas morning, my young son burst into our bedroom well before dawn, vibrating with excitement. "Mommy, Daddy, get up! Come see all the presents under the tree!"

I (who had been up late wrapping those presents) reminded him that he could play with everything in his stocking now, but the presents under the tree had to wait until it was time for the whole family to get up.

“I know,” he replied, “but I need you now because I won't be able to stop myself.”

Delighted, I jumped out of bed. Why was I happy when my son was essentially confessing to a crime in advance?

Because as a behavioral scientist who studies goal pursuit, I knew that what he was doing was exactly right (and impressively self-aware for a seven-year-old).

He wanted to make the right choice but realized he’d struggle with the temptation to peek at the presents. So, he changed the situation (asking for my help) to avoid the conflict and favor success.

Struggle is trouble

Struggle is trouble

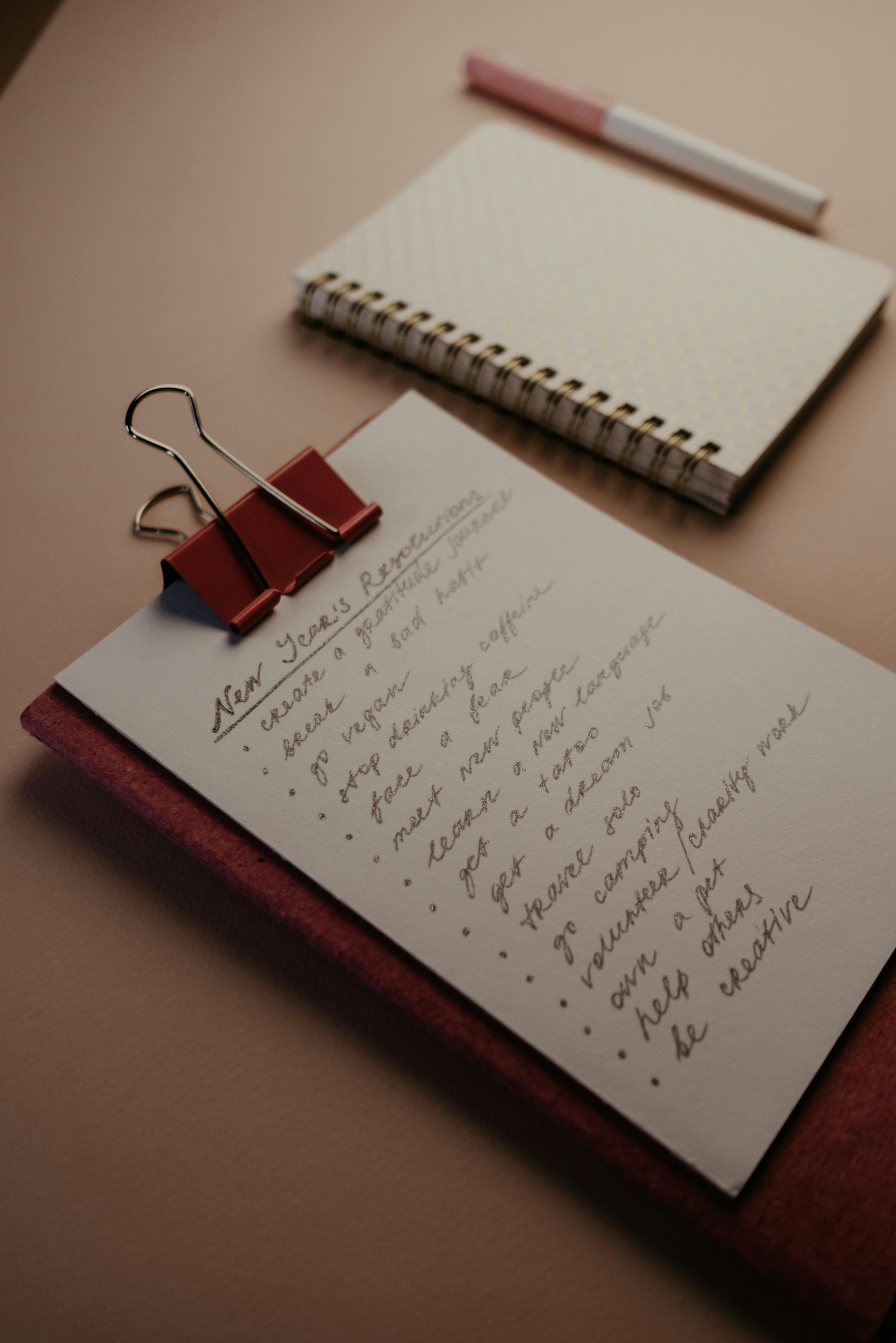

If you are among the millions who made a New Year’s resolution for 2025, you probably started out feeling optimistic. But many resolutions are soon broken—mainly because they usually require complex, long-term behavior change (think exercise, eating, finances, relationships, academics … ).

Popular culture often reinforces the idea that we “should” be able to simply muster up the willpower to do hard things (like exercise or study) and resist enjoyable activities (like eating tasty-but-unhealthy food or scrolling social media).

But while willpower alone can work well for one-and-done goals—like donating blood—for longer-term pursuits, this approach creates ongoing conflict and struggle. It is miserable to experience and a recipe for failure.

A better way

A better approach is to anticipate conflict and take action to avoid it entirely. In fact, research finds that people with high self-control don’t necessarily fare better than the rest of us when faced with temptation. Instead, they achieve their goals by proactively curating their circumstances.

For example, a student might leave their phone (and friends) behind before sitting down to study. Someone focused on eating well might prep a healthy meal (and remove sweets from the house) before coming home hungry and tired after work.

Happily, this kind of planning is a skill that anyone can learn and improve.

Anticipate goal conflict

To avoid conflict with a goal, first, you have to anticipate that it could happen. This can be harder than it seems.

For example, you might know (or be) someone who is consistently late yet still expects no issues with being on time. (I expect to wake up 30 minutes earlier than usual, overlooking a long history with the snooze button.)

In recent research, my co-authors and I wondered why people might not expect conflict with their goals—despite having experienced it before. We found that when people think about a series of past conflicts as being more different from each other (i.e., varied), they expect less conflict in the future. However, focusing on similarities among (even the same) past events increased how much conflict they expected.

In recent research, my co-authors and I wondered why people might not expect conflict with their goals—despite having experienced it before. We found that when people think about a series of past conflicts as being more different from each other (i.e., varied), they expect less conflict in the future. However, focusing on similarities among (even the same) past events increased how much conflict they expected.

A helpful exercise for anticipating conflict is to imagine failing to achieve your goal and then brainstorm possible reasons why. For example, someone with a goal to go to the gym after work might imagine conflicts from having to work late, unexpected family demands, low energy, or forgetting to bring gym clothes. Once you identify potential issues, you can plan around them.

Avoid conflict with situational strategies

A situational strategy entails managing your environment to reduce the goal conflict your future self (maybe just a few minutes into the future) has to contend with.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution—a good strategy is one that addresses your conflict. Some examples:

- Curate focus: Ward off digital interruptions by deleting social media and gaming apps, installing distraction-blocking software, or just leaving devices behind (!!!). Remove distractions before sitting down to work or study. If focusing from home is challenging, it’s worth spending time (and maybe money) to get to an office or co-working space.

- Create contextual cues: You will remember to floss if the container is on top of your toothbrush. Put the gym bag in the car at night, and it can’t be forgotten in the morning rush.

- Automate: For financial goals, set up automatic bill pay and savings deposits (and ruthlessly cancel unnecessary subscriptions). Batch cooking or meal services help “automate” what you eat.

- Recruit help: My son knew he wouldn't touch the forbidden presents if I were there. Plan to be with others who advance your goal (and when possible, limit contact with those who interfere).

None of us has a crystal ball or total control over our circumstances, but if you anticipate goal conflict and plan around it, even small changes can make a big difference!

====

Footnote: Delve deeper into resolutions and results to establish enduring habits for a New-Year’s-Resolution-reality.

- Discover insights into Americans’ New Year’s resolutions, including their motivations and successes, or lack thereof, here.

- Learn more from examinations of the psychology behind self-control in everyday situations and the practice of shaping an environment to maximize benefits for goal achievement.

- Review the full study (by Luis Abreu, Sarah Memmi, and Jordan Etkin), showing that seeing a broader range in types of previous conflicts, as a general perspective, reduces anticipation for future conflict.

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Washington DC: Tour of the U.S. Capitol