How to build a geologic time machine

Ajay Limaye is Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Virginia College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. As a geoscientist, his research focuses on how rivers shape landscapes, from our backyard to distant fringes of the solar system, and is found in journals like Geology and Geophysical Research Letters. His teaching explores how geoscience can stretch our senses of space and time. Limaye’s scholarship was recently recognized with a Faculty Early-Career Development (CAREER) Award from the National Science Foundation.

Ajay Limaye is Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Virginia College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. As a geoscientist, his research focuses on how rivers shape landscapes, from our backyard to distant fringes of the solar system, and is found in journals like Geology and Geophysical Research Letters. His teaching explores how geoscience can stretch our senses of space and time. Limaye’s scholarship was recently recognized with a Faculty Early-Career Development (CAREER) Award from the National Science Foundation.

Take a trip around Charlottesville, and it’s easy to see the rivers surrounding the city. Stroll through the Dell, and you are accompanied by Meadow Creek. Ride a bike down Avon Street, and you will whiz right over Moore’s Creek. Or head east from any Bodo’s, and you will eventually hit the Rivanna River.

Wherever you live, chances are there is a river nearby. Globally and over centuries, societies have grown around rivers as hubs for fresh water, corridors for shipping and transportation, and rich habitats for fish and other creatures. Pause the next time you are next to one of these watery neighbors. As you hear the water trickle by, you might even hear the echoes of deep time.

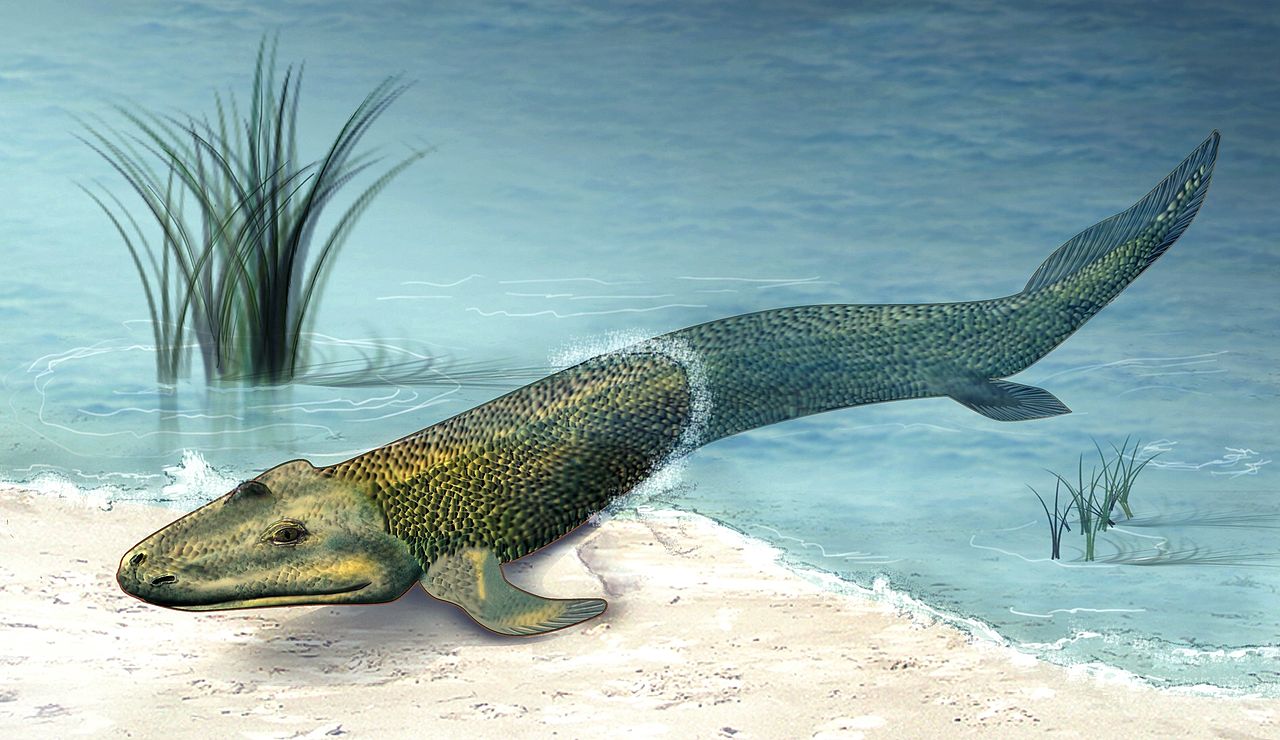

That’s because rivers are not just entwined with the surrounding landscape – they are also intimately tied to the history of the planet. Imagine that you could climb into a time machine and travel all the way back to the Devonion Period, about 375 million years ago. By a river bank, you might see a strange creature called Tiktallik – perhaps one of our earliest ancestors – using its specialized fins to make the first awkward steps onto dry land. Go even further back to the Proterozoic period, 1.2 billion years ago, and you will find rivers flowing across alien landscapes devoid of any trees or shrubs. Go deeper in time still, before there was a hint of breathable oxygen on Earth’s surface! Then, travel to Mars, where you might see rivers flowing into lake-filled craters.

These visions seem fantastical, but they’re all supported by geologic evidence. So, while we’re all used to seeing rivers flowing across a landscape, I like to think of rivers as flowing across time, linking the past, present, and future of planets.

My branch of geoscience, called geomorphology, is all about trying to figure out how the landscapes around us came to be. This work is often inspiring: to look out on the Grand Canyon or the New River gorge is to feel a sense of awe. But solving the puzzle of how these inspiring landscapes developed is a confounding challenge. On a planet 4.6 billion years old, we humans are very late to the game. So late, it turns out, that 99.96% of Earth’s history transpired before modern humans evolved. Add to that the humbling fact that landscapes often change so slowly they can appear frozen in place, and you realize that we just don’t have enough time to see most landscapes take shape.

So, how can we wade into these staggering depths of time? Well, it turns out that that time machine we imagined actually exists, and you’ve probably already climbed in one. It’s called a sandbox. Many a toddler would be proud to demonstrate how to build a mini-mountain with a shovel and then bring it crashing down with a torrential flood from a water bucket. This child’s play illustrates a helpful fact: miniature landscapes change much faster than real ones. While any sandbox-landscape is a distant cousin of the real thing, it can still help us imagine what’s possible without having to wait for a thousand years.

A river formed in a physical experiment at St. Anthony Falls Laboratory, University of Minnesota.

Landscapes sometimes tell their stories so slowly that they are hard to comprehend – but with help from geologic time machines, we can imagine what they might say.

Over several years, I’ve been working with colleagues at the University of Virginia to build a sandbox for science up on Observatory Hill. The design uses high-tech gear – including an automated hydraulics system to mimic river flows and sea-level change and a precise topography scanner to capture landscape patterns – all within a custom-built basin the size of a small swimming pool. We’re excited to see what secrets of landscapes we can discover in this space and will focus on testing theory for how rivers have responded to changes in climate over geologic time.

At the laboratory, we’ll be working hard in a small space to forge new paths into deep time. As you walk your own path in Charlottesville or beyond, remember that this journey into space and time is all around you.

Testing the water system in the new basin. The large working space is equipped with high-precision technology to control water flows and measure evolving landscapes.

- UVA Club of Pasadena: Hoo-liday Party

- UVA Club of Middle Tennessee: Hoo-liday Party

- UVA Club of Culpeper: Hoo-liday Party