The “My Lai Massacre” – Lessons from 50 Years Ago

Fred Borch is a lawyer and historian. He was Professor of Legal History and Leadership at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School for 18 years. He served 25 years in the Army as a uniformed attorney. After retiring from active duty, Fred took a job in the U.S. Government as the only career historian whose focus was exclusively on military legal history. He has seven degrees, including an M.A. in history from the University of Virginia. Fred has lectured and written extensively on the My Lai Massacre and its impact on war crimes prosecutions. In March 2018, he appeared on C-SPAN as part of a panel discussing the tragedy and its place in history.

Fred Borch is a lawyer and historian. He was Professor of Legal History and Leadership at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School for 18 years. He served 25 years in the Army as a uniformed attorney. After retiring from active duty, Fred took a job in the U.S. Government as the only career historian whose focus was exclusively on military legal history. He has seven degrees, including an M.A. in history from the University of Virginia. Fred has lectured and written extensively on the My Lai Massacre and its impact on war crimes prosecutions. In March 2018, he appeared on C-SPAN as part of a panel discussing the tragedy and its place in history.

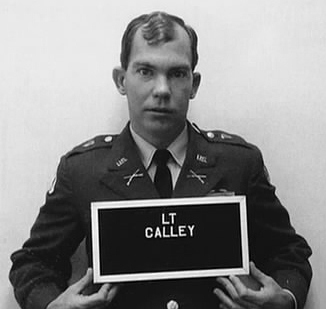

On March 16, 1968, Army 2nd Lieut. William L. Calley and his platoon murdered between 350 and 500 unarmed and unresisting Vietnamese civilians at the small South Vietnamese village of My Lai-4. While the so-called “My Lai Massacre” has been forgotten by most Americans today—if for no other reason than the majority of men and women living today in our country were not yet born—the war crime deserves to be remembered. The killings at My Lai were a horrific event and a stain on the reputation of America’s fighting forces.

Tried by a court-martial, Calley was found guilty of premeditated murder. The military jury sentenced him to be confined at hard labor for life, but his sentence was greatly reduced by senior officers after the trial. Moreover, except for Calley, all other soldiers escaped punishment for their misconduct at My Lai. This is the bad news. However, something positive came out of My Lai because the military learned important lessons from the terrible event—lessons that have changed how the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard conduct military operations today. Just as importantly, there has never been another American war crime like what occurred at My Lai.

On that morning, Calley and his platoon expected to be in a firefight with Viet Cong guerrillas as soon as they got off their helicopters in My Lai. Yet there were no military-age males in the village, only women, children, and old men. Nonetheless, Calley ordered his men to round up all the inhabitants. He also told Private First Class Meadlo “to take care of them,” referring to a large group of Vietnamese villagers. Calley then walked away. Returning a few minutes later, he asked Meadlo why he had not taken care of the villagers. Meadlo answered: “We are. We are watching them.” Calley replied: “No, I want them killed!”

Calley and Meadlo then opened fire on the Vietnamese, and over the next four hours, the American soldiers murdered between 350 and 500 innocent civilians. No one knows the exact number of those shot and killed because the war crime was not investigated until more than a year had passed (senior Army officers orchestrated a cover-up), and the tropical climate of South Vietnam made it difficult to gather evidence of the dead.

Four officers and two enlisted soldiers were court-martialed for the events at My Lai, but only Calley was convicted. After a lengthy trial at Fort Benning, Georgia, an all-officer jury deliberated an unprecedented 75 hours before returning with a verdict of guilty for 22 counts of premeditated murder. Calley had claimed at trial that he had only been following the orders of his company commander, Captain Ernest Medina, to kill everyone in the village. The jury, however, rejected this defense to find Calley guilty.

While Calley was sentenced to confinement at hard labor for life, his sentence was drastically reduced by senior officers in the months following the trial. The result was that Calley only served about five months before being paroled.

In retrospect, it was always clear that Calley was a poor leader and soldier. As one of his men later put it: “He [Calley] couldn’t read no darn map and a compass would confuse his ass.” Perhaps the My Lai Massacre would never have occurred if Calley had not been at My Lai-4.

In the months and years following the tragedy, the military learned at least three lessons from My Lai. First, the Army determined that integrating lawyers into military operations would alleviate situations like those at My Lai. If uniformed attorneys educated and trained in the Law of Armed Conflict were on the battlefield with commanders, their presence would help commanders to ensure that combat operations were conducted in accordance with the law—and decrease the likelihood that Americans in uniform would commit war crimes. The second lesson learned from My Lai was that prosecuting war crimes is significant. Prosecutions deter American soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines from committing war crimes. They also demonstrate to our Allies and foes that Americans are serious about obeying the Law of Armed Conflict—because it is the law and it is morally right. Third, the U.S. military learned that preventing war crimes required instruction in the Law of Armed Conflict regularly. That’s why every American man and woman in uniform today receives in-depth training on the law relating to combat operations. The My Lai Massacre remains a black mark in American history, but it resulted in changes that increased awareness of and obedience to the law and improved the American military.

In the months and years following the tragedy, the military learned at least three lessons from My Lai. First, the Army determined that integrating lawyers into military operations would alleviate situations like those at My Lai. If uniformed attorneys educated and trained in the Law of Armed Conflict were on the battlefield with commanders, their presence would help commanders to ensure that combat operations were conducted in accordance with the law—and decrease the likelihood that Americans in uniform would commit war crimes. The second lesson learned from My Lai was that prosecuting war crimes is significant. Prosecutions deter American soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines from committing war crimes. They also demonstrate to our Allies and foes that Americans are serious about obeying the Law of Armed Conflict—because it is the law and it is morally right. Third, the U.S. military learned that preventing war crimes required instruction in the Law of Armed Conflict regularly. That’s why every American man and woman in uniform today receives in-depth training on the law relating to combat operations. The My Lai Massacre remains a black mark in American history, but it resulted in changes that increased awareness of and obedience to the law and improved the American military.

- Behold – The Art of Giving a Compliment

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Men's ACC Basketball Tournament - UVA Fan Events

- UVA Northern Virginia Programs Fair

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication