The Freedman’s Bank and the Racial Wealth Gap in America

Justene Hill Edwards is an Associate Professor in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History. A 2022 Andrew Carnegie Fellow and a 2023 Mellon New Directions Fellow, her forthcoming book, Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank (October 2024, W.W. Norton), explores the history of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. She is also the author of Unfree Markets: The Slaves’ Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina. Her research investigates slavery’s role in the long history of economic inequality in America, focusing on the 18th and 19th centuries. Always highlighting the lives of enslaved and formerly enslaved people, Hill Edwards studies the relationship between economic and political freedom for people of African descent in the United States.

Justene Hill Edwards is an Associate Professor in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History. A 2022 Andrew Carnegie Fellow and a 2023 Mellon New Directions Fellow, her forthcoming book, Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank (October 2024, W.W. Norton), explores the history of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. She is also the author of Unfree Markets: The Slaves’ Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina. Her research investigates slavery’s role in the long history of economic inequality in America, focusing on the 18th and 19th centuries. Always highlighting the lives of enslaved and formerly enslaved people, Hill Edwards studies the relationship between economic and political freedom for people of African descent in the United States.

On October 8, 1937, an African American woman named Mrs. J. B. Metz from Clarksburg, West Virginia, penned a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. At the time, she was in dire financial straits. The nation was climbing out of the Great Depression, which disproportionately affected African Americans like Metz the hardest. Metz hoped that her request would ease some of her financial stress. She wrote that she had in her possession a bank deposit book that tracked deposits made between May 2, 1871, and June 7, 1873. The last recorded balance was $962.28, and the account belonged to Susan and Katie Morphy, Metz’s mother and grandmother. The deposit book reflected an account with the defunct Freedman’s Saving and Trust Company, also known as the Freedman’s Bank, founded in March 1865 and forced to close in July 1874.

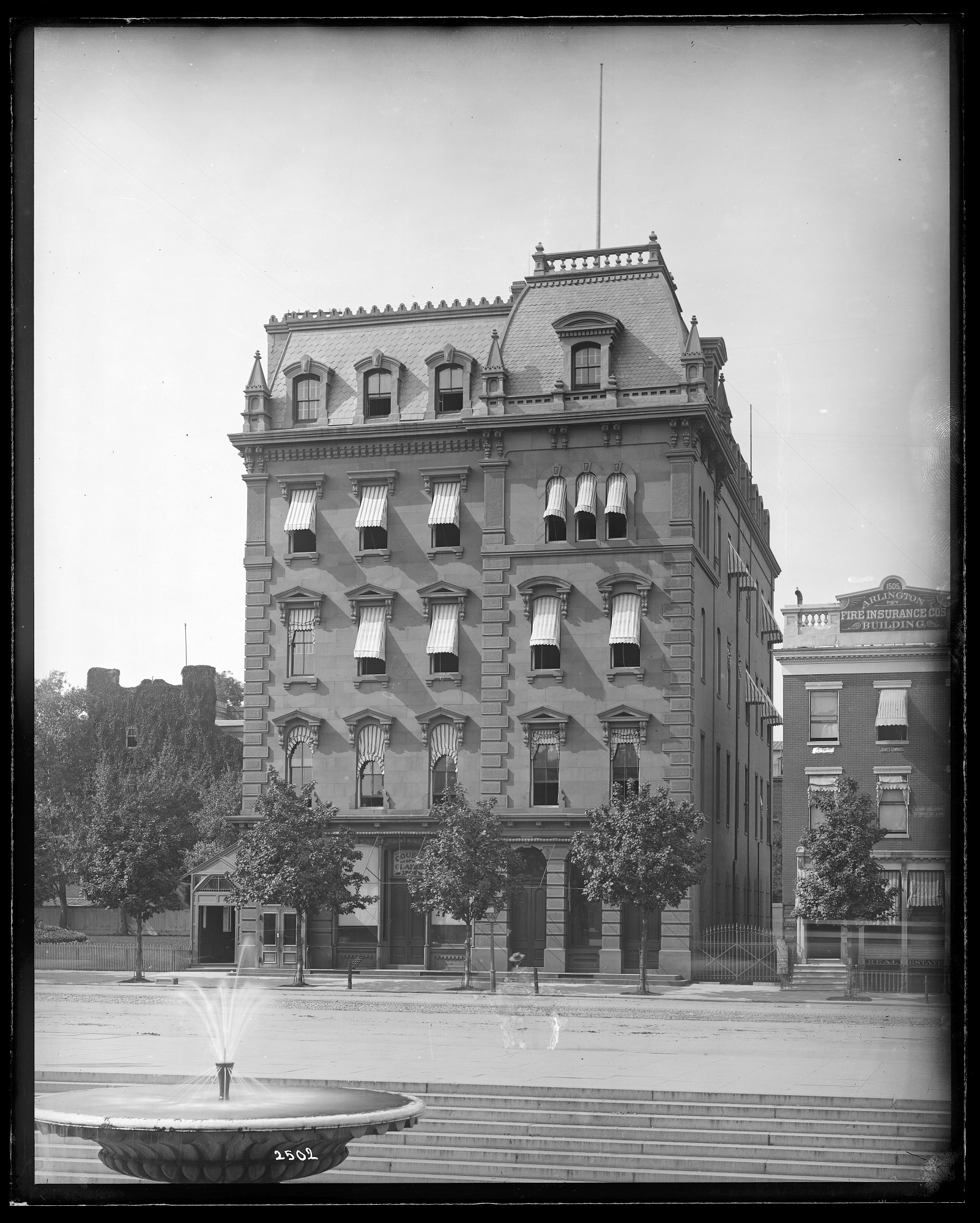

The Freedman’s Bank was a private financial institution founded by a group of white bankers, abolitionists, and philanthropists. It was celebrated by white Americans and African Americans alike for what it represented: the potential economic power of African Americans who just emerged from slavery. When people such as Susan and Katie Morphy deposited money into the Freedman’s Bank, they were absorbing the bank’s message that opening an account would help formerly enslaved people assimilate into the body politic by embracing the supposed benefits of capitalism.

The Freedman’s Bank grew steadily in its first five years. By 1870, African Americans had deposited $12.6 million (approximately $292 million today) into accounts in 30 branches across the mid-Atlantic and the South. As African Americans’ hard-earned money flowed into the bank’s coffers, it was infiltrated by one of the most influential bankers in America: Henry D. Cooke. Henry Cooke was the president of the Washington, DC branch of Jay Cooke & Co., America’s first investment bank. A politically astute lobbyist, Cooke eagerly accepted a spot on the Freedman’s Bank Board of Trustees and quickly controlled the bank’s finance committee. He led the charge to amend the bank’s charter. The Freedman’s Bank would no longer operate as a savings bank to accept the deposits of the formerly enslaved. Instead, the bank, with Congress’ approval, would operate as a commercial bank and make loans to increase the bank’s profitability. This move portended the bank’s demise and put African Americans’ money in jeopardy.

The Freedman’s Bank grew steadily in its first five years. By 1870, African Americans had deposited $12.6 million (approximately $292 million today) into accounts in 30 branches across the mid-Atlantic and the South. As African Americans’ hard-earned money flowed into the bank’s coffers, it was infiltrated by one of the most influential bankers in America: Henry D. Cooke. Henry Cooke was the president of the Washington, DC branch of Jay Cooke & Co., America’s first investment bank. A politically astute lobbyist, Cooke eagerly accepted a spot on the Freedman’s Bank Board of Trustees and quickly controlled the bank’s finance committee. He led the charge to amend the bank’s charter. The Freedman’s Bank would no longer operate as a savings bank to accept the deposits of the formerly enslaved. Instead, the bank, with Congress’ approval, would operate as a commercial bank and make loans to increase the bank’s profitability. This move portended the bank’s demise and put African Americans’ money in jeopardy.

As the bank’s trustees began making millions of dollars in loans to their white business partners, African Americans continued opening accounts and depositing money into the bank. By 1872, the bank counted over 70,000 accounts and over $31.2 million (approximately $774.6 million today) in deposits. Yet, this was when the bank’s foundations started to crack. A financial panic in 1873 exposed the bank’s fragilities. It was overleveraged. Though bank depositors had been placing millions of dollars in their accounts, in late 1873 and early 1874, depositors could not withdraw their money. Instead, they were made to wait weeks to retrieve the contents of their accounts. Not even famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whom the bank’s trustees convinced to accept the role as the bank’s president in March 1874, could restore Black peoples’ confidence in the bank. On June 29, 1874, Congress ordered the bank to suspend operations. The 61,144 depositors who still held accounts, many of whom poured their lives’ savings into this financial institution, lost what remained in the bank. By July 1874, depositors only had collectively $3 million in their accounts.

Black depositors hoped that the federal government would come to their aid. Instead, they would spend the next 60 years pleading with federal authorities to hold the bank’s trustees accountable. They appealed to their Congressmen, Senators, Attorneys General, and, in the case of Mrs. J. B. Metz, U.S. Presidents. In her October 1937 letter, Metz wrote, “It hurts me to think that my people needed this money for the necessities of life and saw times when they were hungry and hoping for this money and receiving no notice about it, lost it by no fault of their own.”

Surprisingly, Metz received a response five days later, on October 13, 1937. The letter was not from President Roosevelt but from George R. Marble, a chief clerk with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). Marble conveyed that, unfortunately, the OCC had officially ceased looking into individual inquiries regarding the bank’s closing. Furthermore, Metz would not be able to recover the monies in her family members’ accounts because “there are no further assets to be collected.” There was nothing Marble could do to help Metz recover the money her mother and grandmother put into their Freedman’s Bank accounts. Despite her ancestors absorbing the bank’s messages of hard work and saving, she could not reap the financial benefits of their diligence.

The experiences of African Americans such as Mrs. J. B. Metz reflect not only the tragedy of the Freedman’s Bank failure but also the longer history of economic inequality in America. The Freedman’s Bank represented the economic potential of African Americans made manifest. However, the bank’s collapse illustrates the extent to which we as a nation must confront the tragedies of history to understand the pervasiveness of economic inequality today.

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- Virginia Club of New York x The Essay Conqueror: The College Essayscape

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication

- UVA Club of Richmond: Hoos at the VMFA Jazz Cafe