Becoming President Jefferson

John A. Ragosta, a historian at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello, has taught law and history at the University of Virginia, George Washington University, and Oberlin, Hamilton, and Randolph Colleges. Currently a fellow at Virginia Humanities, Mr. Ragosta will again serve as the faculty leader at this June's Summer Jefferson Symposium on UVA Grounds.

John A. Ragosta, a historian at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello, has taught law and history at the University of Virginia, George Washington University, and Oberlin, Hamilton, and Randolph Colleges. Currently a fellow at Virginia Humanities, Mr. Ragosta will again serve as the faculty leader at this June's Summer Jefferson Symposium on UVA Grounds.

Thomas Jefferson referred to the Election of 1800 as a “Revolution,” returning the nation, he insisted, to the “Spirit of ’76.” Certainly, the election had an enormous impact; after 1800, avowed Jeffersonians ruled for most of two score years.

That election and its principle of the peaceful transfer of power among political parties have been lionized for over 200 years.

But it almost did not happen that way.

In 1798, a Federalist Congress adopted the Sedition Act, effectively making it criminal to criticize the president or Congress (although the vice president – Jefferson – was fair game). For Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican supporters, attacks on the press meant that free and fair elections themselves were at risk. The law undermined “the elective principle, by taking away the information necessary,” one Virginia congressman warned. Silencing the press would mean that “republicanism will be entirely brow-beaten,” Jefferson told James Madison, and a powerful government could not be controlled at the ballot box.

Until recently, historians grossly underestimated the impact of the Sedition Act, one referring to prosecutions as “paltry.” But recent scholarship shows that scores of opposition newspaper editors were convicted; leading Democratic-Republican newspapers were closed.

Desperate, Jefferson drafted the Kentucky Resolutions that threatened to nullify federal laws that the state unilaterally declared unconstitutional. Madison’s Virginia Resolutions, somewhat ambiguously, threatened state interposition between the federal government and citizens.

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions precipitated a forceful and astonished backlash. Newspapers warned that such unilateral state action to undermine a federal law would lead to the dissolution of the union, possibly civil war. Some reports had Virginia arming for a possible conflict with the federal government and sister states. Patrick Henry, at George Washington’s impassioned plea, came out of retirement to denounce the states’ rights agenda of the Jeffersonian resolutions. Ten of sixteen states rejected their logic, several warning that disunion seemed to be the goal.

Chastened, Jefferson and Madison retreated from the radical states’ rights position. (That agenda would be resurrected in Jefferson’s name in the run-up to the Civil War, bursting over Fort Sumter in 1861.) Refocusing his campaign on principles of a small, democratic government, Jefferson won the election of 1800 not through state interference with federal laws but because his supporters took their grievances with the Sedition Act, high taxes, and an aggressive federal government to the ballot box.

The election itself, though, was particularly vicious. Snarling attacks accused Jefferson of being an atheist, John Adams of being a monarchist. While neither candidate personally vilified their political opponent, rhetoric ran wild, encouraging a belief that the people were deeply, perhaps irrevocably, divided (even without the influence of modern gerrymandering and social media).

While Jefferson won the election (albeit with the aid of the Constitution’s 3/5ths clause that gave additional electoral power to slave states), a new crisis immediately presented itself. In the electoral college vote, Jefferson tied with Aaron Burr, his ostensible vice president. With Federalists committed to preventing Jefferson’s election still in control of the “lame duck” Congress that would resolve the electoral college tie, further chaos threatened.

Both Jefferson and Burr maneuvered behind the scenes in an effort to win the contested vote, although the record of their clandestine machinations is not particularly clear. Federalists floated ideas that would have kept both Democratic-Republicans out of office. While Jefferson would later deny that violence was ever considered, an explosion seemed imminent. Both Pennsylvania and Virginia were reportedly preparing to use their militias if Jefferson was denied the presidency. Meeting Adams in the streets of Washington, Jefferson warned angrily that bloodshed threatened.

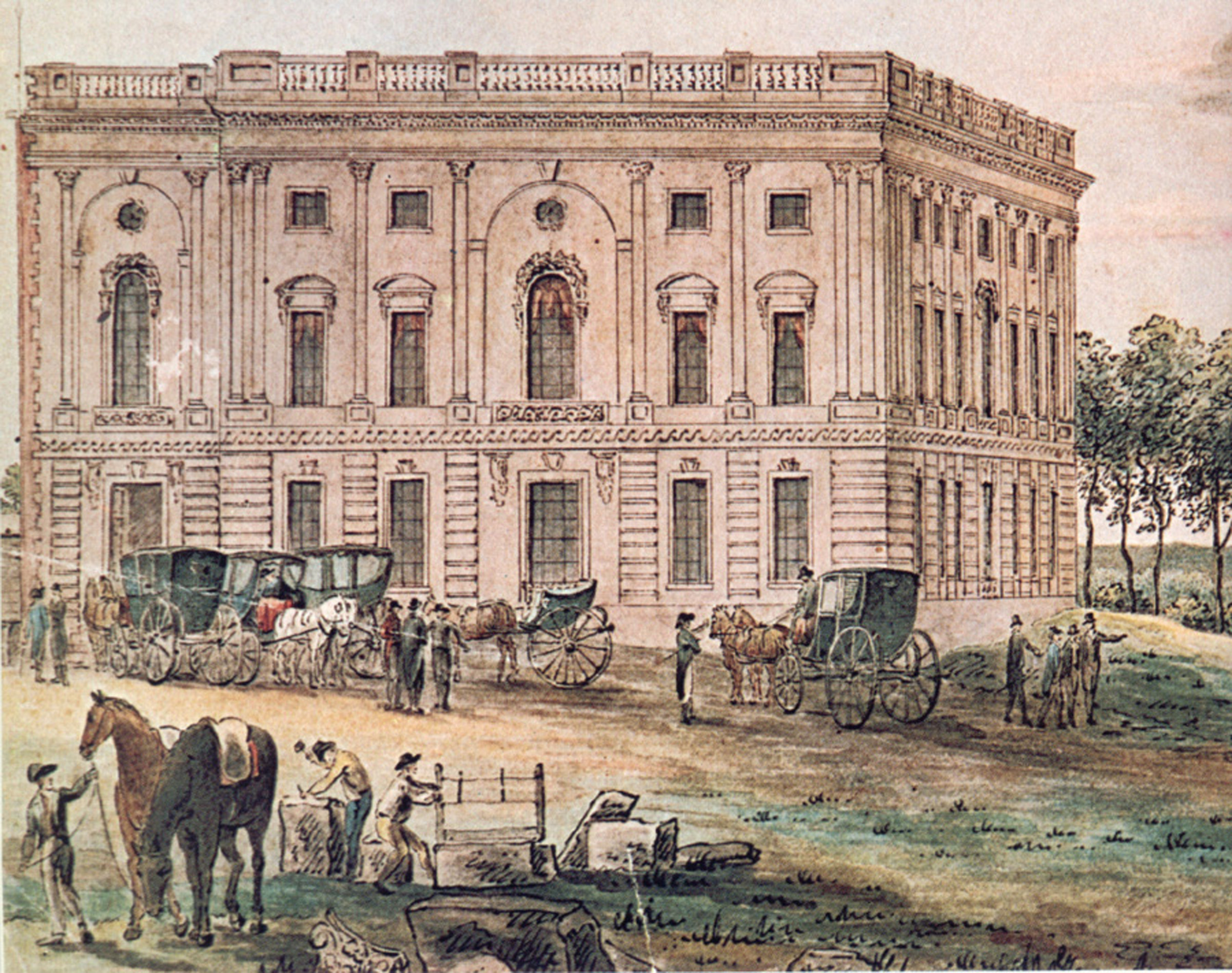

After complex political compromises that are still not fully understood, the congressional deadlock was resolved on the 36th ballot on February 17, 1801. On March 4, 1801, Jefferson has inaugurated the third president of the United States under the Constitution. The crises were over. America becomes a largely Jeffersonian republic. The peaceful transfer of power after an election became a U.S. hallmark for 220 years.

After all of this, though, Jefferson was deeply conscious of how close the system came to being undone. The constitutional “Clock” had almost “run down,” Adams admitted years later. Perhaps more accurately, the constitutional system was almost driven over a cliff by bitter partisan battles.

Read in this light, Jefferson’s famous first inaugural address takes on a wholly different voice. Reminding us that “every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle,” Jefferson sought to pull the nation back from bitter partisanship. Declaring “we are all republicans, we are all federalists,” Jefferson did not simply seek to quiet political opponents with pablum. Rather, the new president understood that the union for which he had dedicated his life had come ominously close to destruction, and now, with enormous responsibilities descending on his shoulders, perhaps Jefferson knowingly retreated from some of the partisan positions of the 1790s.

Perhaps what some of his political contemporaries and modern historians have seen as President Jefferson’s hypocrisy in failing to implement many of the more extreme limitations on the government and empowerment of the states that his party advanced while in opposition reflects instead a careful reassessment.

In any case, it is essential to read Jefferson’s presidency in light of the crises that preceded it, crises in which Jefferson was often an active participant and sometimes an instigator.

In June, Lifetime Learning’s Summer Jefferson Symposium will be discussing these and other aspects of Thomas Jefferson’s presidency.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party