Mapping the Historic Green Books

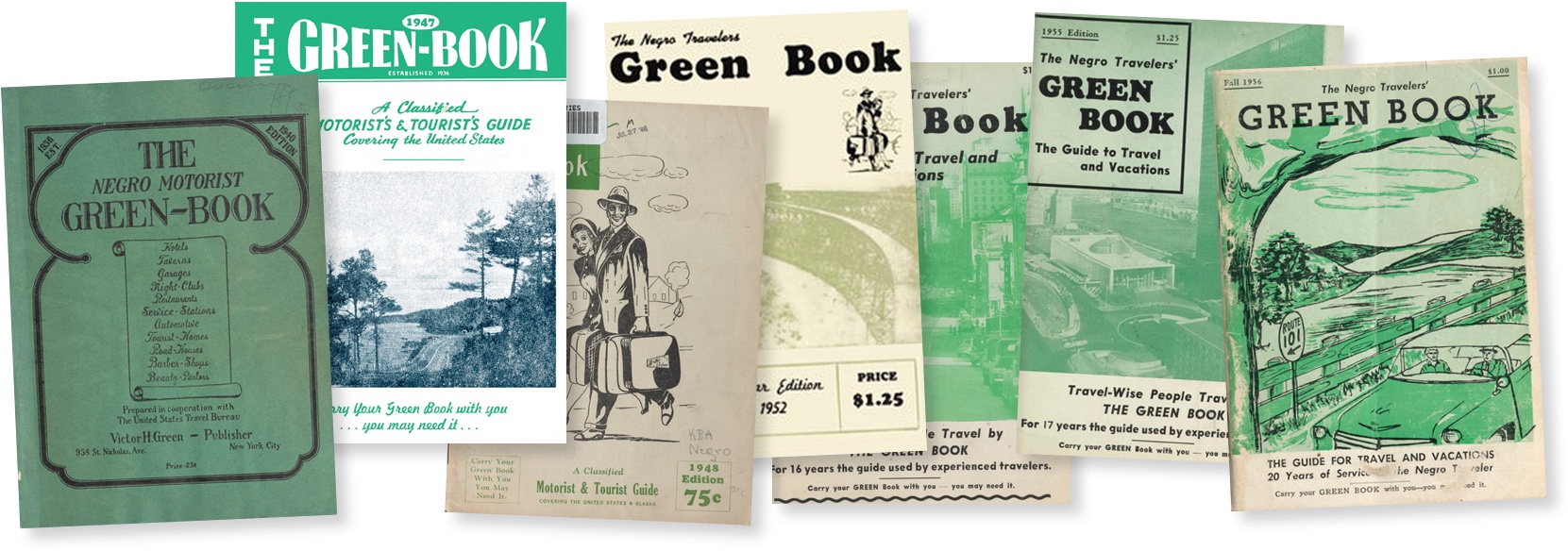

On the afternoon of January 26, 2022, University of Virginia alumni, friends, and families joined Malo Hutson, Dean of the UVA School of Architecture as he moderated a conversation about the historic Green Books with Louis Nelson, Vice Provost for Academic Outreach at UVA, second-year student Olivia Pettee, and alumna Catherine Zipf. UVA alumni and student volunteers are spearheading an important digital project to document and map Green Book sites across the country. The Green Book was an annual publication that listed motels, restaurants, and other establishments where African American travelers could stay and patronize during the Jim Crow era. In this Thoughts From the Lawn blog, learn more about the Green Books with follow-up answers to audience questions.

How many copies of the Green Book were printed per year? Where were these books advertised and purchased?

The Green Book published one edition annually starting in 1937. However, there were no editions published from 1942 to 1946, due to paper rationing during World War II. Editions 1963-1964 and 1966-1967 are the only double-year issues. At its height, Victor Green printed about 20,000 issues per year.

The Green Book was initially distributed throughout Green’s network of postal workers. However, what set The Green Book apart from other black travel guides was its partnership with Esso gas stations. James A. Jackson and Wendell P. Alston, who were Esso marketing executives, distributed and promoted The Green Book at Esso gas stations as they traveled across the country.

I thought that the Green Book only covered the U.S. What other countries did it include and for what years?

The Green Book published international listings beginning in the 1949 edition, which had sites from Mexico, Canada, and Bermuda. By the 1962 edition, international listings had expanded to include the Caribbean, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the West Indies. The 1963-1964 and 1966-1967 editions are the most comprehensive and clearly aimed for an international audience; their covers have the subtitle “International Edition: For Vacation Without Aggravation.” These international editions included listings from all 50 states, Canada, the Caribbean, Latin America, Europe, and Africa.

How was Victor Green able to collect all of this information? How often was the Green Book updated? Why did some listings not have addresses?

Victor Green collected information in a few different ways. In the early years of the publication of The Green Book, Green relied on his connections as a mail carrier to gather recommendations and for these first editions, he scouted the listings himself. However, once The Green Book expanded to produce new issues each year, Green began asking business operators and readers to provide addresses and information for the listings. He also called on readers to mention The Green Book while traveling and have those businesses get in touch. Addresses may be missing because many of these recommendations relied on word of mouth.

Regarding the Paramount and Jefferson theaters in Charlottesville, VA that were listed for only one year, do you think their status as segregated facilities was the cause? Do you think other listings were "dropped" if there was negative feedback from users?

While it is unknown if segregation was the primary cause of the Jefferson and Paramount theaters appearing only in 1939, for the first few editions, Victor Green had close oversight over the sites that were listed. Green did solicit feedback from readers about the listings, as he wrote: “If this guide has proved useful to you on your trips, let us know. If not, tell us also, as we appreciate your criticisms and ideas for the improvement of this guide from which you benefit.” It is certainly possible that listings were discontinued due to negative user feedback.

Does your project include just surviving structures, or do you also document those that have been demolished? How many of the places listed in The Green Book are still in operation? Can you roughly estimate, overall, the percentage of sites that survive? What loss of locations can you estimate was due to highways and other federal actions that ‘gentrified’ the neighborhoods where Green Book locations existed?

Our project documents all the sites, even those that no longer exist. Right now, we estimate that about 25-45% survive, but we are still looking for sites, so that number is likely to change. Far fewer are still in operation in their original form; in Rhode Island, only 1 (The Biltmore Hotel) out of 24 sites is still what it originally was.

The causes of demolition are interesting and sometimes contradictory. Certainly, highway development was a key factor, but not the only factor. In Newport, RI, four out of eight original sites were demolished due to new construction, a new police department, a park, and a public-housing development. We are finding that gentrification often cut both ways. In Providence, the creation of the College Hill National Register Historic District pushed out the African American community living along Benefit Street, putting an end to six Green Book businesses in that neighborhood. At the same time, the College Hill NRHD also preserved the buildings, so the buildings themselves survive. Three others just outside the boundaries of this district do not.

Will you be including the other African-American travel guides or those that served the LBGTQIA+ and Jewish communities in your project?

At the moment, our focus is on the sites listed in The Green Book. The New York Public Library’s digitization of their collection has made studying those sites very easy. In contrast, the other African American guides are not as accessible and would require a different approach than ours. Travel guides for the LBGTQIA+ and Jewish communities as also not as well documented or accessible. Original copies of any of these guides, including The Green Book, are very rare. When people purchased the next issue, they often threw out the old one (do you still have your old phone book or AAA guide?). If you are the lucky owner of any of these guides, please make sure to deposit them in an archive for future study and preservation.

In terms of the National Register of Historic Places, has a historic context been developed to outline areas of significance and integrity as guidance for NR documentation?

As far as we know, the National Park Service has been working on this issue, specifically in reference to Green Book sites that are adjacent to Route 66; we are not sure of the status of this effort. A number of states, among them Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia have been working on including Green Book sites in their preservation plans. All these efforts require an inventory of sites, which is precisely what our project will provide. As our project moves forward, this is the type of work that we hope to foster.

Are there any Black student scholars who are actively involved in Green Book research? Is UVA ahead of the curve, or are other colleges in the area doing similar projects?

So far, we have partnered with several universities around the country. Students at North Carolina State University undertook a class project that researched quite a number of the state’s sites. We also had two students at South Carolina University take on researching some of those listings as an independent project. Right now, students at SUNY Oneonta are working on sites in upstate New York, and we are hoping to begin working with students at Montclair State University on sites in northern New Jersey. Also, we are not quite ready to make an announcement, but there is a program being created for HBCU students that we hope will bring new partners to the project.

Could the presenters speak to whether the project has any reparative aspects within its research and data-crunching processes? Does the structure of the project itself address the current institutional, resource, and power imbalances that are also the legacies of the era being studied?

Our goal is to document all of The Green Book’s listings, thereby bringing to light the previously hidden landscape of African American travel—this is a huge task and we are working hard against the clock to achieve it before more Green Book sites are lost. As we progress, we hope our project will support other efforts at reparations and at addressing power imbalances.

How can we contact those working on the project to find out about research in our states, to contribute information to the project, or to join the effort?

We’d love to hear from you! You can reach Catherine through Twitter @CatherineZipf, LinkedIn Catherine Zipf, and through her website, www.catherinezipf.com. Catherine will be delighted to put you in touch with researchers in your area.

To support this program with a gift, visit the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH).

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: Hoos Reading Hoos January Book Club

- UVA Club of Atlanta: UVA Women's Basketball at Georgia Tech