Memories of Jimmy Carter

Barbara A. Perry is the Gerald L. Baliles Professor, Director of Presidential Studies, and Co-Chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at UVA’s Miller Center. She also serves on the Board of the White House Historical Association. Follow her @BarbaraPerryUVA.

Believe it or not, I knew about Jimmy Carter when he was still “Jimmy Who?” (That’s Who, not Hoo!) Even his own mother, the colorful “Miss Lillian,” exclaimed when he told her that he was running for president, “President of what?”

I first saw him in person, when he was Georgia’s governor, attending a 1973 Democratic National Committee meeting in my hometown of Louisville. As a high-school senior, already completely obsessed with American politics, I answered the call of my civics teacher to serve as a page at the DNC gathering.

Two years later, the 1975 National Democratic Issues Conference, also held in Louisville because our new Kentucky senator Wendell Ford was a party power broker, convened major contestants for the 1976 presidential nomination. Along with several thousand party influencers, I attended the gathering, again as a page, but this time trying to determine how I would vote in my first presidential election the next year.

Former governor Carter arrived in Louisville from the campaign trail, where he had been focusing on Iowa, the first state in the party’s nomination contest. If he could pull off an upset win in the caucus state, he would no longer be “Jimmy Who?” At the issues conference, Carter faced a formidable array of competitors, including Democratic luminaries from Congress and ambassadorial posts. Senators Henry Jackson, Birch Bayh, and Fred Harris, Congressman Morris Udall, and Ambassador Sargent Shiver all brought higher name recognition and longer résumés to the stage.

Hoping his brand of moderately liberal southern populism would attract support, along with his experience as a nuclear Navy officer and as a small businessman with roots in Georgia peanut farming, Carter had to prove his credibility in foreign affairs. It might have been a blessing that at the issues convention he was assigned to speak on the international policy panel.

A fellow University of Louisville student and I, both political science majors, were astounded by Carter’s performance, as he skillfully answered questions from Senators Philip Hart and Gary Hart (no relation) and other experts in the field. Although Senator Henry Jackson, a venerable voice in foreign affairs on Capitol Hill, also participated in the roundtable discussion, Carter bested him with his command of facts, references to his international travel, and insightful approach to defense policy in the midst of the Cold War. His U.S. Naval Academy education certainly bolstered his credentials and knowledge.

Common wisdom, even among seasoned Democratic strategists, however, squared with my friend’s and mine: how could this virtually unknown former Georgia governor win the nomination against such a better-known field? Proving that we should not pursue careers in election prognostication, we decided to support Morris Udall, the Lincolnesque Arizona congressman.

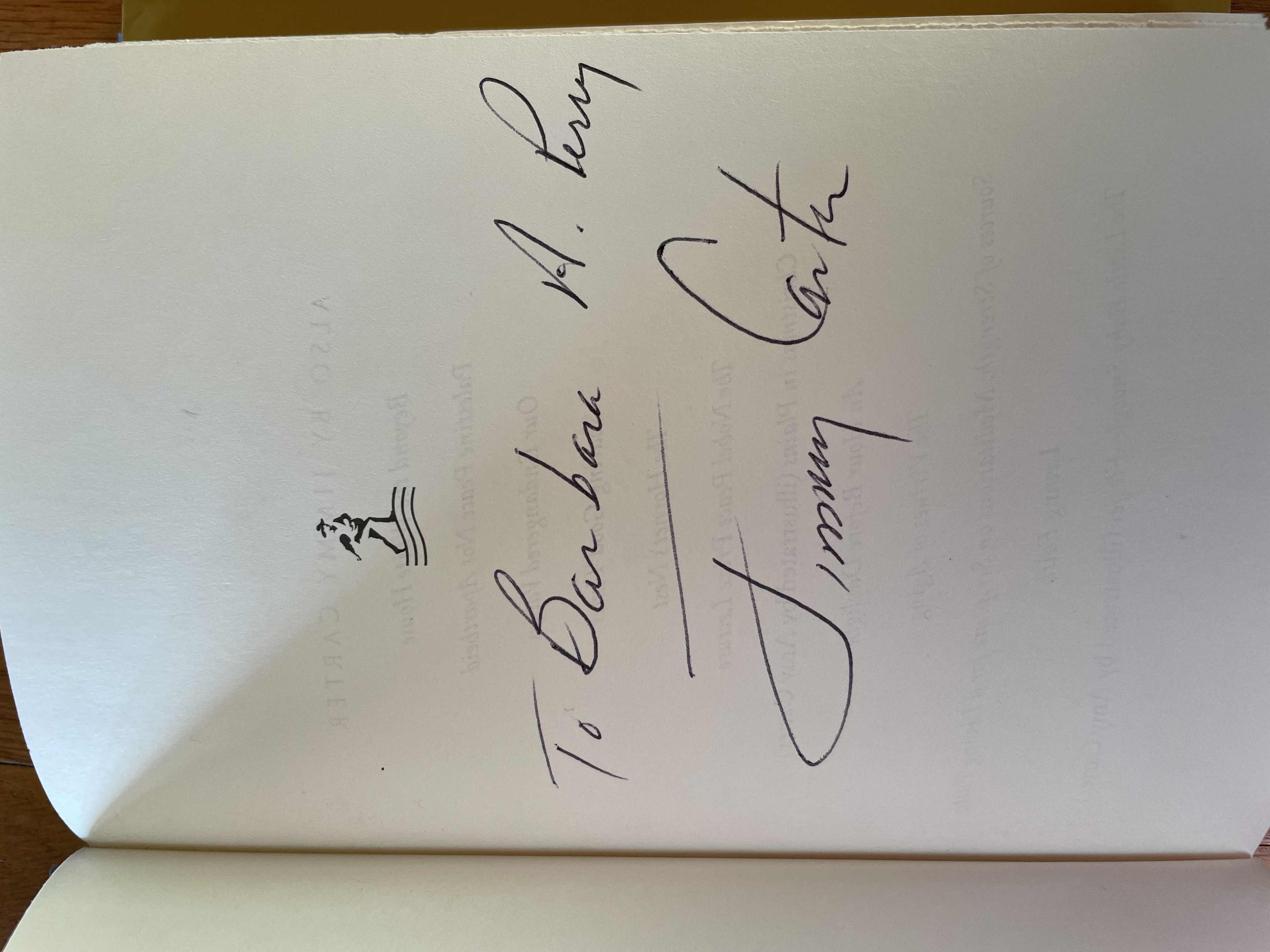

When Carter garnered the nomination, starting with his win in Iowa, we switched our allegiance to the party’s standard bearer. Returning from my first Washington experience, as an intern for Senator Ford in the summer of 1976, my parents welcomed me home with a copy of Carter’s campaign biography, Why Not the Best? My mother, a lifelong Democratic, had taken me to see Senator John F. Kennedy one month before our fellow Catholic’s presidential victory. My more conservative dad, a World War II veteran, on the other hand, accompanied me to a 1962 midterm election rally at Louisville’s airport, headlined by former President Dwight Eisenhower. Too young to collect campaign memorabilia at the JFK and Ike rallies, I eagerly snagged a green and white Carter campaign poster in fall 1976 when the Democrats held a rally at the Louisville Fairgrounds.

After casting my first presidential vote for the pride of the Peach State, I hopped on a city bus to watch returns at Democratic headquarters in downtown Louisville. My college friend and I then caught a ride to the nearby Holiday Inn to gather in its ballroom for an election night party or wake, depending on the outcome. About midnight, it became clear that a call in the neck-and-neck race with incumbent President Gerald Ford wasn’t forthcoming, so we tried to book a room. The desk clerk turned us two naïve college kids away for want of credit card! We sheepishly had to call our parents (via pay phone) to drive in from the suburbs to collect us.

I stayed awake until 4 a.m. to hear the contest called for Carter, whereupon I posted a victory sign on my parents’ bedroom door and dropped exhausted into bed. The next day I started to plan on achieving my very first bucket-list goal—attending a presidential inauguration. I took a Greyhound bus to Cincinnati and transferred to an Amtrak train on the coldest night ever recorded in the Queen City (20 below zero). The train and tracks between Ohio and the nation’s capital froze up several times, delaying my arrival, but I made it in time to witness the gracious transfer of power from Ford to Carter and then run down Pennsylvania Avenue to see the new president and his wife, Rosalynn, walk hand-in-hand to the White House, in a show of downhome modesty.

I’ll also never forget seeing Hamilton Jordan, dressed in blue jeans, exit a taxi on the south side of the White House to start his first day as President Carter’s chief of staff. As I walked along 17th Street, a half-block from the Executive Mansion, I discovered $100 in the gutter, which financed my flight back to Louisville.

I’ll also never forget election night 1980. By then a graduate student at Oxford, I felt homesick not to be watching returns in my native country. So I went with British friends to see a midnight showing of All the President’s Men. By the time I returned to my dorm room, it was still only mid-evening on the American East Coast, but the BBC was already calling the race for Ronald Reagan in a landslide. The Iranian hostage crisis, hyper-inflation, and fuel shortages all contributed to Carter’s loss.

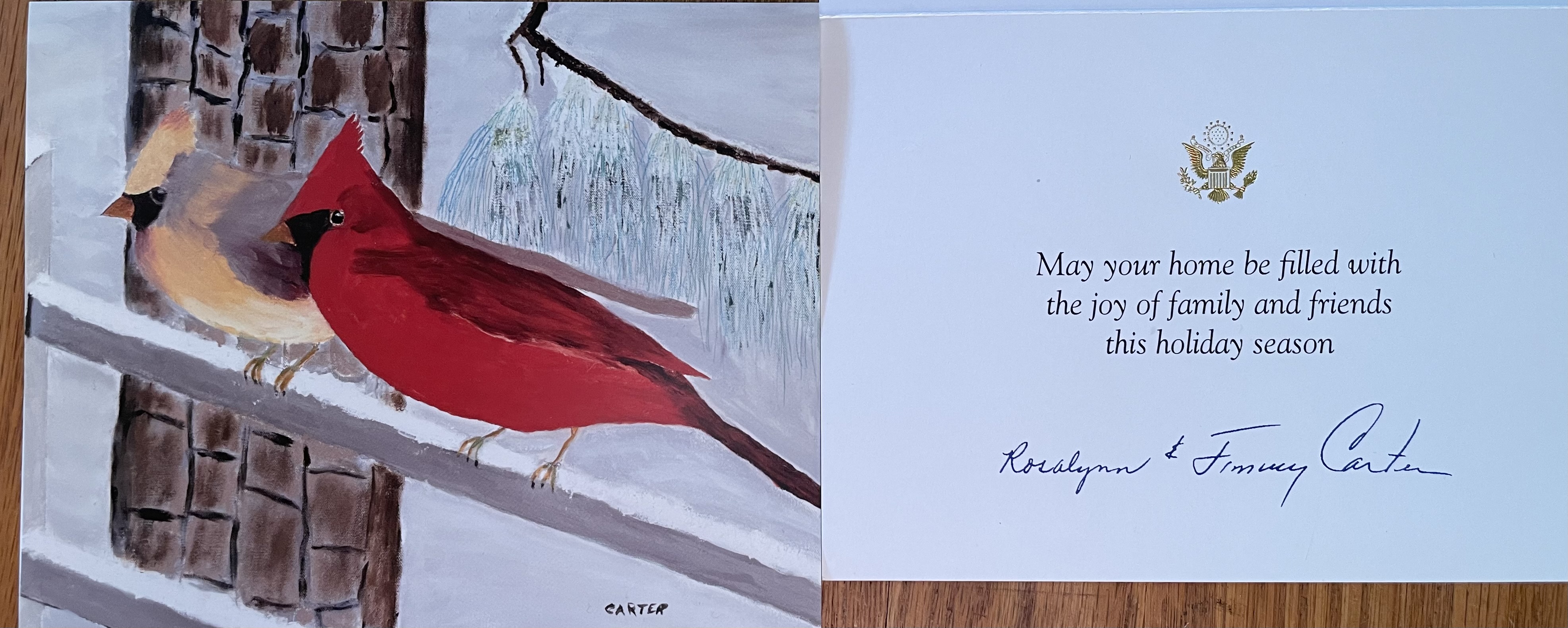

I couldn’t help but feel a wave of sadness when I learned the 98-year-old ex-president had entered hospice, holding records for the longest-lived POTUS and most enduring presidential marriage, and recognized (even by opponents) as the creator of a model post-presidency. I guess I’ll always think nostalgically about my first presidential vote.

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Vietnam: J-Term Farewell Social

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: Hoos Reading Hoos January Book Club