Women’s Equality Day: 104 Years of Voting Rights and the Road Ahead

Corinne Field is Associate Professor of Women, Gender & Sexuality at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on the intersections of age, gender, and race in United States history. Field’s current book project, Feminist Aging in Nineteenth-Century America: Old Age, Justice, and Power, offers a collective biography of radical women who fought for old age empowerment and justice in the nineteenth century. Her next project, Looking Old: A U.S. History, will consider the aesthetics of oldness across hierarchical relations of gender, race, and class. Field is the author of The Struggle for Equal Adulthood: Gender, Race, Age, and the Fight for Citizenship in Antebellum America (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Corinne Field is Associate Professor of Women, Gender & Sexuality at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on the intersections of age, gender, and race in United States history. Field’s current book project, Feminist Aging in Nineteenth-Century America: Old Age, Justice, and Power, offers a collective biography of radical women who fought for old age empowerment and justice in the nineteenth century. Her next project, Looking Old: A U.S. History, will consider the aesthetics of oldness across hierarchical relations of gender, race, and class. Field is the author of The Struggle for Equal Adulthood: Gender, Race, Age, and the Fight for Citizenship in Antebellum America (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Women’s Equality Day, August 26, marks a hundred and four years since the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution removed sex as a barrier to voting—yet we have still not elected a woman President of the United States. Senator James David "JD" Vance’s now infamous critique of “childless cat ladies” offers one clue as to why. In 2021, Vance appeared on the Fox News show Tucker Carlson Tonight and alleged that: "we are effectively run in this country, via the Democrats, via our corporate oligarchs, by a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices they've made, and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too." He named Vice President Kamala Harris, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as examples.

Since this interview resurfaced, the Democratic response has focused on defending reproductive freedom and the maternal capacities of childless women. Harris' stepchildren and their biological mother came forward to champion the Presidential candidate's parenting skills. Jennifer Aniston and Harris herself underlined the importance of IVF, which Vance would ban. But Vance's criticism goes beyond reproductive choices to mobilize a longer tradition of ridiculing progressives—whatever their gender or parental status—as miserable old maids or evil old women who seek only to destroy the happiness of others.

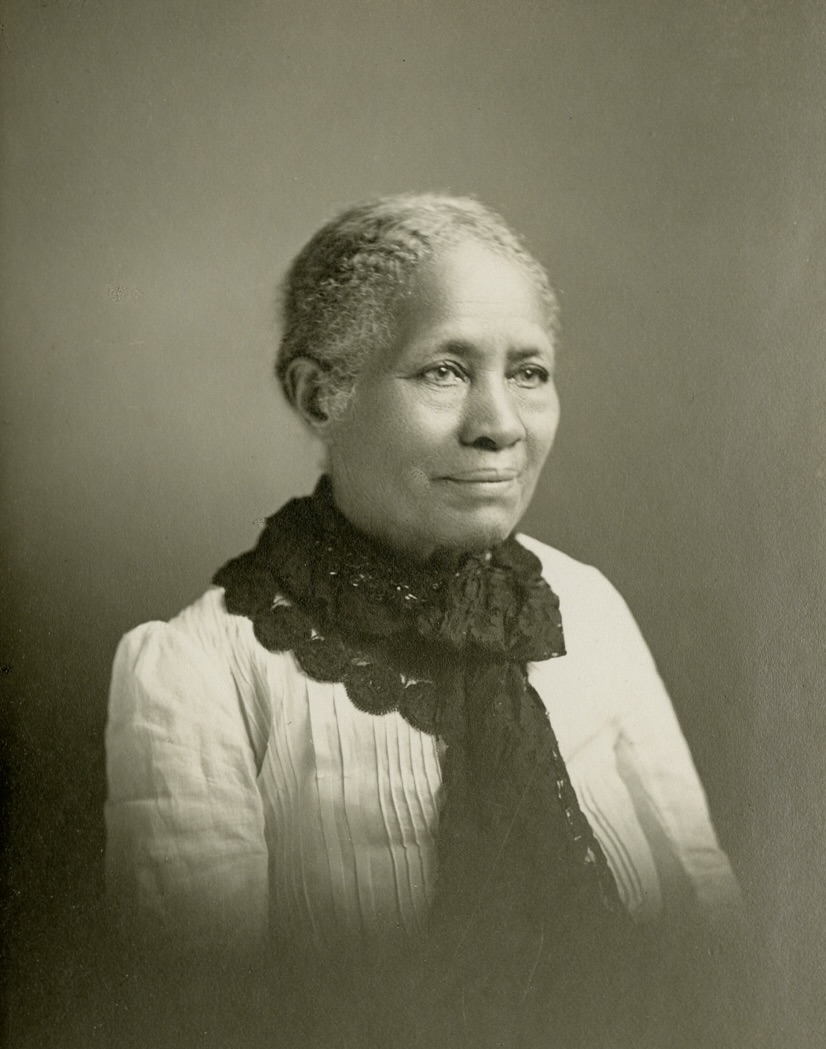

c. 1890, Hist. Soc. of Pennsylvania

Compare Vance’s comments to how the Pittsburgh Chronicle described the first national women’s rights convention organized by abolitionists and feminists in 1850: “about ninetenths of the progressive women are old maids... and they are determined to upset everything, not in the hope of bettering their own miserable situation, but with the intention of making others... as miserable as they are themselves.” That most of the women at the convention were, in fact, married did nothing to blunt this critique. Indeed, men could also be portrayed as old women beyond their childbearing years, as when the New York Herald referred to the convention as a gathering of “old grannies, male and female.” Portraying male abolitionists in the prime of life, such as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, as “grannies” functioned to associate them with the supposed unhappiness and unattractiveness of old women. One reporter went even further and compared the “malicious disposition” of the men and women at the convention to “the old witches of Massachusetts.” This potent mix of misogyny, ageism, and anti-Black racism functioned to associate those advocating for freedom and equality with the figures of the spiteful old maid or the evil old witch, both motivated by a desire to undermine the happiness of others.

Popular culture amplified the associations between women’s rights and spiteful old maids. A comic valentine from the 1850s pictured a wrinkled woman with devil’s horns over the text: “You ugly, cross and wrinkled shrew, You advocate of women’s rights, No man on earth would live with you.” The humor magazine Yankee Notions sounded no different than the mainstream press in joking that women’s rights activists were all “either old maids, or divorced wives” who just needed “good husbands” to be happy. Ridicule, not pronatalism, was the point.

shrew,” Comic Valentine Coll.,

Library Company of Philadelphia

Abolitionists and women's rights activists pushed back. Some emphasized that their women leaders were happily married mothers. Newspaper editor Jane Grey Swisshelm responded to criticism of the 1850 Worcester convention by defending white antislavery activist Lucretia Mott as "a wife, a mother and a grandmother." This mattered little to conservative critics who persisted in characterizing Mott as an "old maid."

Others embraced and repurposed the slur "old maid.” Frances E. Watkins, one of the first African American women hired to travel the country as an antislavery lecturer, wrote a tongue-in-cheek letter to the Anti-Slavery Bugle in 1859 describing herself as an "old maid... going about the country meddling with the slaveholders' business." Later that year, Harper published a short story in the Anglo-African Magazine that contrasted the “bitter agony” of an abusive marriage to the contentment achieved by an “old maid” who found fulfillment as a professional writer, abolitionist, and social reformer. Watkins herself chose to marry a year later, and today, she is better known by her married name, Frances E. W. Harper. Still, for the rest of her life, she continued to promote Black women's political empowerment as vital to both personal happiness and the cause of freedom.

As supporters of Harris respond to Vance's comments, it is worth keeping in mind that there is more at stake than reproductive choices. The historical roots of this attack lie not in pronatalism but in the opposition to movements for racial and gender equality. Overcoming this opposition will require not only defending childless women—or rallying under the banner of “Cat Ladies for Kamala”—but embracing the broad movement for American freedom that conservatives have so long opposed.

====

Footnote: Read more about Women’s Equality Day here.

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- UVA Club of Greater Orlando: UVA vs. Stetson Baseball Pre-Game Celebration

- Virginia Club of New York x The Essay Conqueror: The College Essayscape

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication