Practice: Integrity’s Music

JoVia Armstrong is Assistant Professor of Music at the University of Virginia College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. In 2015, she won the Best Black Female Percussionist of the Year through the Black Women in Jazz Awards and received the 3Arts Siragusa Foundation Artist Award in 2011 for her work as an educator. JoVia sits on the executive board of Chicago's AACM as Secretary.

JoVia Armstrong is Assistant Professor of Music at the University of Virginia College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. In 2015, she won the Best Black Female Percussionist of the Year through the Black Women in Jazz Awards and received the 3Arts Siragusa Foundation Artist Award in 2011 for her work as an educator. JoVia sits on the executive board of Chicago's AACM as Secretary.

It took me 27 years to finally make it to Cuba.

Since 1996, Francisco Mora-Catlett, one of my mentors and son of the late Elizabeth Catlett, has guided me to become a contemporary hand percussionist. When I was an undergraduate student, Francisco often walked with me to Tower Records and recommended which records I should purchase and listen to. These records varied from American jazz artists like Baby Dodds, Chick Webb, Return to Forever, Tito Puente, John McLaughlin, and Herbie Hancock to Afro-Cuban artists such as Chucho Valdes, Bamboleo, Machito, Giovanni Hidalgo, Tata Guines, and more. I studied these artists daily, and they have significantly impacted my musical journey.

In the '90s, musicians had to constantly rewind cassettes and CDs for hours to study talented instrumentalists and music. This study allowed them to dive deep into the brains of the musicians and composers they analyzed, identifying their unique "voice". Many of today’s music students are not doing this type of research because technology has made this same study less necessary for our students. Now, apps can slow down music so listeners can hear each note and even identify the chords being played. While this technology can be helpful, it may also eliminate the desire for in-depth study, time, and repetition necessary for true mastery.

In the '90s, musicians had to constantly rewind cassettes and CDs for hours to study talented instrumentalists and music. This study allowed them to dive deep into the brains of the musicians and composers they analyzed, identifying their unique "voice". Many of today’s music students are not doing this type of research because technology has made this same study less necessary for our students. Now, apps can slow down music so listeners can hear each note and even identify the chords being played. While this technology can be helpful, it may also eliminate the desire for in-depth study, time, and repetition necessary for true mastery.

My friend Isaiah Sharkey, a renowned guitarist, notes that while technology can tell you what line to play, it cannot explain why it is played when it is played. While AI uses data to replicate what humans may do, it does not teach why we do it. We don’t need to think anymore. I have heard jazz musicians say that learning and performing Black music comes from a place of struggle and a desire for liberation. If technology removes the need to think as a musician, there is no struggle. And, if we are free from thought, we are enslaved to the data.

I struggled to hear the clave in Afro-Cuban music. It wasn't that the records were inaudible. I needed to immerse myself in Cuban culture from a distance by listening to this music daily and practicing with the CDs as often as possible. I also chose to stop listening to American music for three years straight.

I recall creating a strict practice schedule. My calendar told me when to practice, which practice room to reserve, when to take a nap, which lounge and in which building to take that nap, and when to go to the cafeteria to eat. I even practiced in the dark to improve my accuracy. I was very disciplined and committed to my craft. But most importantly, I respected the music. To play it however I wanted to play it would have been disrespectful.

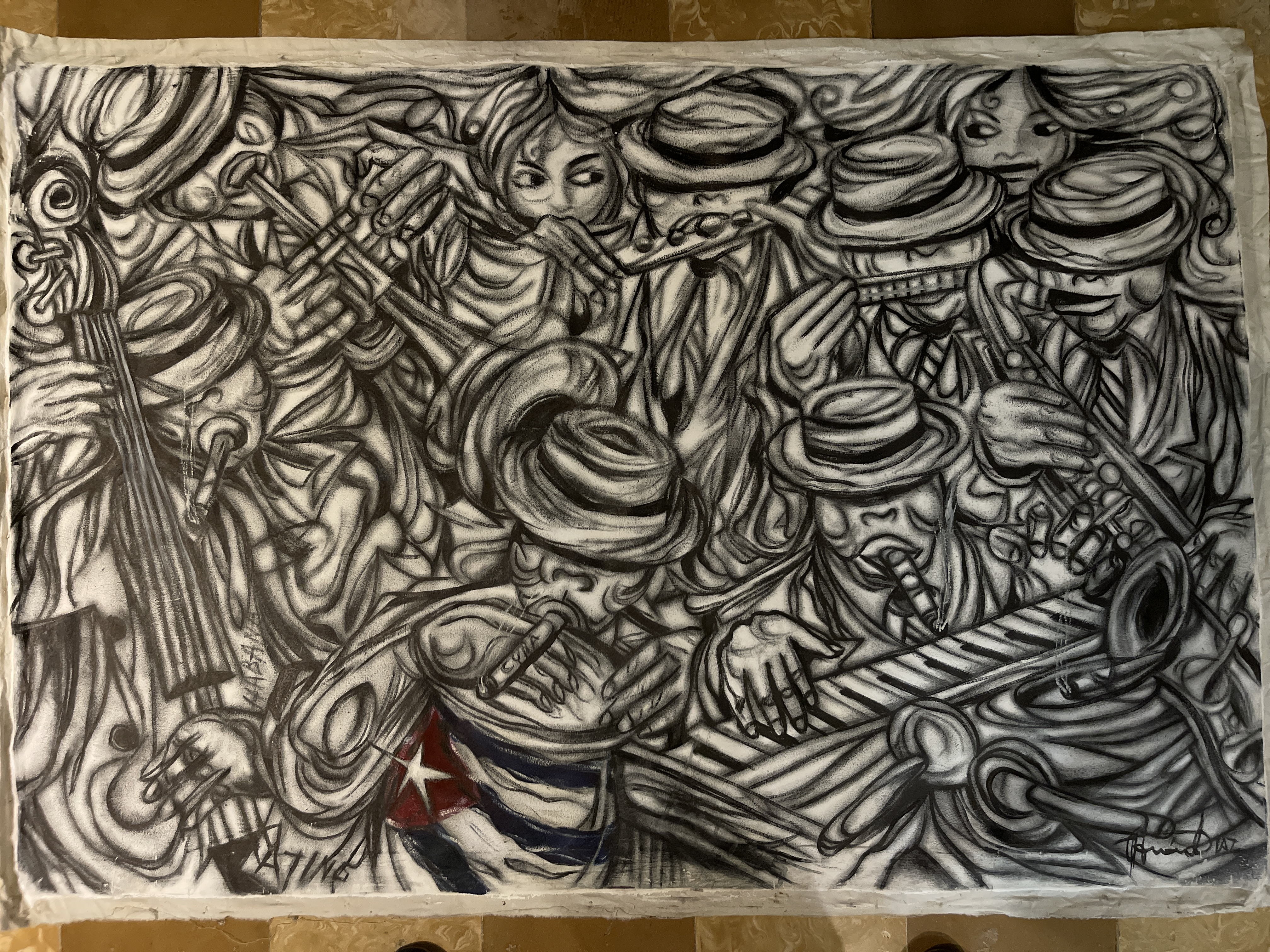

Last year, I went to Cuba for two weeks to study music with Francisco and his wife, Danys “La Mora” Pérez, who runs Oyu Oro Afro-Cuban Experimental Dance Company in Santiago de Cuba as well as New York City, where she and Francisco live. I also studied with Oyu Oro and Cutumba, another Afro-Cuban folkloric group in Santiago. During week two, I studied with Folklorico de Camagüey en Camagüey, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas in Matanzas, and Raíces Profundas en La Habana. We studied conga and bata drum rhythms like Guaguanco, Bembe, Rumba Colombia, Arara, and much more.

Last year, I went to Cuba for two weeks to study music with Francisco and his wife, Danys “La Mora” Pérez, who runs Oyu Oro Afro-Cuban Experimental Dance Company in Santiago de Cuba as well as New York City, where she and Francisco live. I also studied with Oyu Oro and Cutumba, another Afro-Cuban folkloric group in Santiago. During week two, I studied with Folklorico de Camagüey en Camagüey, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas in Matanzas, and Raíces Profundas en La Habana. We studied conga and bata drum rhythms like Guaguanco, Bembe, Rumba Colombia, Arara, and much more.

In Camagüey, their timbales had holes in the drum heads, their drumsticks were broken and worn, and their cowbells were dented. But there was no imperfection in their sound. Every day was in the 90s, and the rehearsal spaces felt even hotter, but they played with intensity. Neither technology, instruments, nor heat stopped the practice of music.

I asked students recently, “Have you ever heard of practicing for eight hours a day?” Most of them thought it was an absurd thing to suggest. They asked me, “Why would you want to do that?” I wish they loved practice as much as I did in undergrad. And I don’t believe that they disrespect the craft of music. I’d rather believe that educators may need to set higher goals for students and create limitations for them to reach those goals. Give them the broken drums and sticks, the guitars that won’t stay in tune, and the MPC2000 XL with just a floppy disk drive. The struggle with limitations offers opportunities to be creative problem solvers. This means the same limitations can provide opportunities to be free of problems.

I asked students recently, “Have you ever heard of practicing for eight hours a day?” Most of them thought it was an absurd thing to suggest. They asked me, “Why would you want to do that?” I wish they loved practice as much as I did in undergrad. And I don’t believe that they disrespect the craft of music. I’d rather believe that educators may need to set higher goals for students and create limitations for them to reach those goals. Give them the broken drums and sticks, the guitars that won’t stay in tune, and the MPC2000 XL with just a floppy disk drive. The struggle with limitations offers opportunities to be creative problem solvers. This means the same limitations can provide opportunities to be free of problems.

Music is sacred. Playing the music of oral traditions isn’t only about playing the right pattern. You must play it with the correct hand positioning and the same intensity while employing the language of the music. While respect is the sidekick of good practice, the love of people, especially the ones responsible for creating the music, is the motivation that drives the discipline to practice. But can we teach students to love…the practice of music?

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party