Freedom to Discriminate?

John Ragosta, author of Religious Freedom: Jefferson’s Legacy, America’s Creed, states that “…we must never return to a situation where people use their claims of religious freedom to avoid laws against discrimination…” Ragosta is a fellow at Virginia Humanities and lead faculty for Lifetime Learning‘s Summer Jefferson Symposium at the University of Virginia.

John Ragosta, author of Religious Freedom: Jefferson’s Legacy, America’s Creed, states that “…we must never return to a situation where people use their claims of religious freedom to avoid laws against discrimination…” Ragosta is a fellow at Virginia Humanities and lead faculty for Lifetime Learning‘s Summer Jefferson Symposium at the University of Virginia.

We welcome your comments below.

FREEDOM TO DISCRIMINATE?

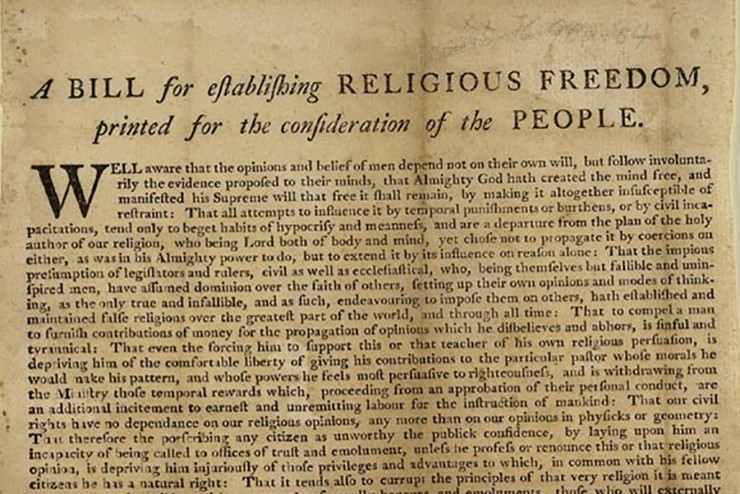

January 16 is Religious Freedom Day, when we commemorate the adoption of Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom. I would urge everyone to read that Statute, a profound and beautiful statement of religious freedom.

Jefferson, recognizing that America would be a “melting pot” of peoples from different lands, ethnicities, and religions, assured us that religious freedom protects “the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and the Mahometan, the Hindoo and the infidel of every denomination.”

Increasingly, though, people are using religious freedom to justify repugnant acts.

Recently, a small town in Minnesota faced a request to permit a white-supremacist church in its community. Town officials, while appalled by the church’s doctrines, issued the required permit, correctly concluding that they had no right under the First Amendment to prohibit it. (John Reinan, “Minnesota Town Votes to Allow White Supremacist Church,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), December 10, 2020.)

Freedom of religion includes the right to believe even abhorrent things. Jefferson made this point in the Statute: “to suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion and to restrain the profession or propagation of principles on supposition of their ill tendency is a dangerous fallacy….”

At the same time, people engaged in otherwise illegal actions – from refusing to bake a wedding cake or give a marriage license for a gay wedding, to refusing to abide by COVID regulations, to refusing to allow an interracial couple to be married at a wedding venue – have claimed an exemption from the laws based on their religious beliefs.

Jefferson was equally clear that these claims do not deserve the constitutional protections of religious freedom.

What’s the difference?

For Jefferson, and for the Supreme Court, the right to believe is essentially unlimited. “Almighty God hath created the mind free,” Jefferson wrote; “all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments, or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness,…”

With this right to believe comes a broad right to worship as you think fit. A church can ban women from being ministers. (Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has recently expanded this ministerial privilege to allow churches to call virtually anyone working in their schools or commercial operations a “minister.”) A church can ban non-whites and preach repugnant doctrines.

Yet, everyone is subject to the law, regardless of religious beliefs. Jefferson uses the easy example of a religion that wishes to practice child sacrifice. Regardless of their religion, that would be illegal, and practitioners would be prosecuted.

Jefferson, though, gives a second example: What if, when the country was at war, Congress prohibited the slaughter of lambs because we needed wool for uniforms and the meat from allowing lambs to grow to adult sheep? Jefferson – obviously thinking of Jewish Passover – said such a law was enforceable and people could not avoid punishment by claiming a religious exemption.

The difference for Jefferson is that beliefs are personal; actions have legal consequences. As he explained in the Virginia Statute, while there should be no restraint or punishment based upon belief, there “is time enough for the rightful purposes of civil government for its officers to interfere when principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order;…” James Madison said the same: “the immunity of Religion from Civil Jurisdiction,” exists only when “it does not trespass on private rights or the public peace….”

Jefferson understood that laws had to be “impartial,” not aimed at the religious practice per se. If a law forbade Jews from slaughtering lambs or forbade the slaughter of lambs for religious purposes, that law would not be impartial and would rightly be found unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court has adopted a similar doctrine of “neutrality.” Laws that neither promote nor discourage religion can be enforced regardless of someone’s religious beliefs. Congress can accommodate beliefs, exempting some practices from law because of their religious nature, so long as that accommodation does not itself promote the religious practice. So, for example, during Prohibition, sacramental wine was exempted.

This is what was at issue in the recent Supreme Court cases striking down COVID restrictions on churches. Those restrictions were said not to be neutral; they restricted churches more seriously than comparably situated businesses. (I have some doubts about those facts, but that doesn’t change the legal doctrine.)

In the Smith case (1990), the Supreme Court explained the neutrality doctrine in an opinion written by Justice Scalia; the Court allowed a prison guard to be fired for using peyote (a controlled substance under a neutral federal law). Congress might have exempted Native American religious practices from that law, but it had not done so.

After that decision, a sympathetic Congress, without a lot of careful consideration, quickly passed the poorly named Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). That law did not change the constitutional doctrine that there is no blanket religious exemption from laws, but it did stack the deck in favor of such religious claims.

Under RFRA, if a person claims that a federal law interferes with their religious practice, they are exempted unless it is shown that the government’s interest in passing the law was compelling and the law was narrowly tailored, i.e. there was no alternative that would equally serve the government interest while not interfering with the religious practice.

Those claiming a right not to bake wedding cakes or avoid COVID restrictions rest their claims on RFRA.

As I suggested, this law was not well thought out and should be repealed.

Claims of religious freedom have often been used to justify vicious and dangerous actions over our history. People claimed that their religion prohibited blacks and whites from dating (much less marrying) in their schools or businesses. Jews were excluded from businesses, housing, and educational opportunities based upon claims of religious freedom. All of those things are now illegal, and one would hope that the Supreme Court would find that the laws against racial and religious discrimination are based on compelling reasons and are properly tailored to their goals.

Now, claims are often made to avoid laws that prohibit discrimination based upon sexual orientation. That some of these claims have been successful in some courts seems implicitly to be based upon a conclusion that sexual orientation discrimination is not as serious as racial or religious discrimination. Those decisions, however, are best left to the Congress, and courts should not be forced into exempting people from anti-discrimination laws.

RFRA should be repealed, and Congress (and state legislatures) should use their authority to accommodate religious practices by excluding them from anti-discrimination practices only when doing so makes sense given the serious nature of the religious claim and the need for an end to the discrimination.

Jefferson would agree.

That brings us back to the church in Minnesota preaching white supremacy.

The law cannot prohibit it from doing so, but we must never return to a situation where people use their claims of religious freedom to avoid laws against discrimination in business, housing, commerce, and education.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party