From Green to Gold: The Fall Transformation of Ginkgoes

Experts at UVA’s Blandy Experimental Farm and State Arboretum of Virginia gave a virtual presentation on the ginkgo tree for Lifetime Learning in November 2020. Below, the Blandy team answers myriad questions that viewers posted in the webinar Q&A. David Carr is the director of Blandy Farm and a research professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia. Chris Schmidt is head arborist, and Ariel Firebaugh is director of scientific engagement, at Blandy Farm.

GINKGO EVOLUTION AND HISTORY

Why did ginkgoes become extinct outside of Asia?

Based on the fossil record, ginkgoes as a group seemed to be declining in their diversity and the extent of their range well before the extinction of the dinosaurs (the end of the Cretaceous Period, 65 million years ago). Their decline coincides with the rise of the angiosperms, eventually becoming the dominant form of terrestrial plant life. Competition with angiosperms was likely an important factor in this decline. For example, highly efficient pollination systems that took advantage of insects and other animal pollinators to disperse their pollen may have given angiosperms a reproductive advantage. More recently (about 5 million years ago), the range of ginkgoes shrank as the climate cooled during repeated glaciations. However, unlike the angiosperms, ginkgoes did not reclaim their range when glaciers retreated, possibly due to the loss of key seed dispersers.

Are there Asian ginkgo species that differ from American species, similar to Chinese chestnut and American chestnut?

There is only one species of ginkgo left on earth, Ginkgo biloba. The ginkgo trees that you encounter in the United States, Europe, or Japan all derive from the ginkgo trees that survived as a small relic population in China. It is correct to point out that the forests of the southern Appalachian Mountains, including here in Virginia, share close relatives in China’s forests, including chestnuts, rhododendrons, magnolias, sassafras, dogwoods, and many, many more.

Are ginkgoes considered a non-native species because they were brought from China?

Are ginkgoes considered a non-native species because they were brought from China?

That is a great philosophical question. In North America, most definitions of “native plant” cite the arrival of Europeans as the time delineation for what is “native” and what is “exotic.” European arrival started the huge trans-Atlantic human-mediated plant migration that continues to this day. A fossil ginkgo with leaves indistinguishable from modern-day Ginkgo biloba was present in North America until the Oligocene (between 23 and 33 million years ago). Most authorities probably consider ginkgo “non-native” in North America, but if your personal preference is to regard it as a “resurrected native,” you can make a good argument.

What is the status of ginkgoes in the area of China where they survived until they became popular ornamental plants?

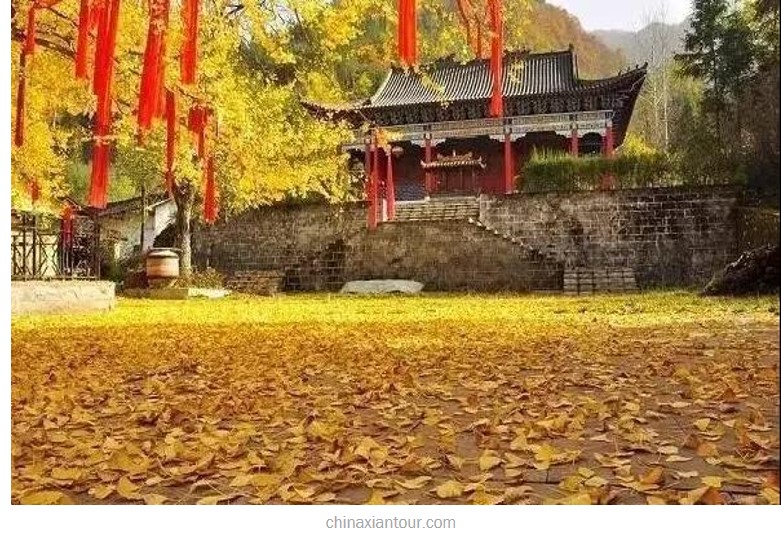

The ancient ginkgo trees growing naturally in various regions of China are surviving for a couple of reasons. The Chinese revere the ginkgo. Many groves are near temples and monasteries and these trees are protected. Because the ginkgo is so resistant to pests and diseases and widely tolerant of various growing conditions, it has continued to survive in Southwestern and Eastern China along the Yangtze River.

GINKGO SEX AND REPRODUCTION

Why isn’t the ginkgo berry considered “fruit?”

Although “fruit” is a very general term in the English language, it has a very precise definition in botany. Technically, fruits are produced only by flowering plants (angiosperms) from the ovary of a flower. True fruits have a layer called the pericarp, derived from the ovary (in fruits like apples or cherries, that is the part that we eat). The pericarp surrounds the seeds, which develop from fertilized ovules. Ginkgo “fruit” is not technically produced by flowers. Instead, it develops from a naked ovule that develops into a seed. The fleshy part of the ginkgo “fruit” (the sarcotesta) develops directly from the seed. All that said, true fruit and ginkgo “fruit” perform the same function for the plant – they serve to attract animals that then serve to disperse seeds to new locations.

Is a ginkgo either male or female? At what age does ginkgo start showing reproductive structures?

For all practical purposes, a ginkgo tree is either male or female. If you have never seen a “fruit” on your ginkgo, it is probably a male (however, it is not impossible that a female is so isolated from the nearest male that fruit production fails every year). The male cones on ginkgoes are quite obscure, and they are produced for a very short period in the spring. They are produced with the leaves on the little stubby “pegs” along the trunk and large branches and resemble the catkins (pollen-producing flowers) of an oak tree. Ginkgoes usually reach sexual maturity and begin showing reproductive structures when they are 20-30 years old.

Does a single gene in a ginkgo seed control whether it yields a male or female offspring?

A group of Chinese researchers just published a paper in October 2020 that has identified a region on Chromosome 2 in the ginkgo genome that seems to be responsible for sex determination. In males, the region contains more than 200 tightly linked genes that appear to function in male sex expression. The reviewers suggest that this is analogous to a Y-chromosome in mammals (including humans). Females lack these genes on Chromosome 2. This discovery will make it easier to determine the sex of a ginkgo before it begins to develop reproductive organs.

Is the sex change in response to environmental or other stressors?

There is not yet a definitive answer for ginkgo. Sex (male or female) seems to be genetically determined in ginkgo. Still, many dioecious plants (plants with separate male and female individuals) do change sex in response to the environment. Because of the need to invest in seed and fruit production, reproduction is often energetically more expensive for females than males, which only produce pollen. In some species of dioecious plants (e.g., the wildflower, Jack-in-the-pulpit), individuals in the most resource-rich environments reproduce as females, and those in resource-poor environments reproduce as males. In other situations, disease can cause a switch from female to male (e.g., in striped maples). Researchers have suggested that this strategy might ensure that a dying tree has a better chance of producing offspring. The odds that a seed from a female tree will mature into a seedling are better than the odds of pollen from a male tree successfully pollinating a female tree and having her seeds mature into a seedling.

Is there any other plant or fossil that has such unique sperm with flagella? How did it evolve?

The earliest plants (e.g., algae) were aquatic, and they had flagellated sperm (as do modern algae). Some of our most primitive land plants also have sperm with flagella, including mosses, ferns, horsetails, and club mosses. Note that during the Carboniferous period, ferns, horsetails, and club mosses dominated the forests and were as large as modern trees, but they all predated the evolution of the seed, a key innovation for life on land. Their flagellated sperm is seen as a holdover from their aquatic algal ancestors, and these species require water in their environments for the sperm to swim to the eggs. This, of course, is a potential liability for a plant that lives on land.

Only two groups of “seed plants” that exist today have flagellated sperm – the cycads and the ginkgo. The other modern seed plants, the gnetales (a tiny group of gymnosperm plants that includes only three genera and fewer than 50 total species), conifers, and angiosperms (the flowering plants that dominate the modern terrestrial environment) do not have flagellated sperm. The pollen grains of these species deliver the sperm directly to the ovule for fertilization, and water is not required.

The cycads are a small group of mostly tropical gymnosperms that superficially resemble palm trees (I often see them planted as landscape trees in Florida or California). DNA evidence suggests that they are the closest living relatives to the ginkgoes. It is most likely that the flagellated sperm of ginkgoes and cycads is a remnant from their ancestors (non-seed plants). The sperm of other groups of modern seed plants have lost their flagella as their reproductive systems became even better adapted to life on land.

GINKGO ECOLOGY

What is the timing of ginkgo coloring and leaf drop each year?

The timing of ginkgo leaf coloring likely varies by location. One study in South Korea found that ginkgo leaves change color sooner at higher elevations and higher latitudes (Park et al. 2017, PLOS ONE). Here at Blandy, late October is usually the best time to see glorious golden ginkgoes. Over the past ten years, the trees in Blandy’s Ginkgo Grove have tended to begin changing color during the third week of October. Golden leaves tend to “peak” around the first week of November and tend to drop during the second or third weeks (see Blandy’s website and Facebook page for weekly October updates). After laying on the ground for a time, the ginkgo leaves turn brown and decompose.

As the day length shortens, chemical changes occur where the leaf petiole is attached to the stem. The stem end forms a protective barrier (the leaf scar), while the separation layer on the petiole side weakens. In gingkoes, it appears this happens simultaneously to all the leaves. Thus, all the leaves are pre-conditioned to drop at the same time.

The leaves of both males and females transform from green to brilliant yellow. Strangely, we noticed this year that the younger trees turned yellow and dropped their leaves before the older trees. Perhaps a microclimate difference?

What can you tell us about the butyric acid that makes ginkgo fruit stink?

Butyric acid is a viscous, colorless substance that occurs naturally in butter, human sweat, vomit… and ginkgo fruit! Commercially, butyric acid is sometimes used as an odiferous additive in fishing bait and stink bombs. Some scientists suspect that Eau de ginkgo may have attracted ancient seed dispersers, encouraging dinosaurs or early mammals to eat ginkgo fruit and “distribute” the seeds far from the parent trees.

Does the scent of the fruit play any role in dispersal? Was it eaten and spread by animals now extinct? What animals eat ginkgo fruit today?

Although most humans regard the smell of ginkgo “fruit” as repulsive, this scent was likely attractive to some group of fruit dispersers during the heyday of ginkgoes in the Mesozoic era. Because gingkoes (including the only living species, Ginkgo biloba) evolved so long ago but then disappeared from almost the entire planet, the question of who dispersed ginkgo seeds is controversial. In the Mesozoic, primitive mammals or even dinosaurs may have consumed ginkgo fruit. Most or all of their primary dispersers are probably extinct, however. Some researchers have hypothesized that the loss of seed dispersers may have contributed to the disappearance of ginkgo from Europe and North America during the ice age. At Blandy, we do find ginkgo seedlings growing far from the Ginkgo Grove, suggesting that some of our local fauna (perhaps opossums and raccoons) are still moving some seeds around. Deer rarely browse on leaves, but they might nibble on fruit too.

Note: So many people asked these questions that we have put game cameras in our Ginkgo Grove at Blandy to try to capture images of the animals that are feeding on our ginkgo “fruit.”

Why doesn’t the ginkgo support caterpillars? Do fungal diseases affect ginkgoes?

Fossil ginkgo leaves show extensive damage from herbivorous insects, so they probably supported extensive insect communities during their heyday in the Mesozoic Era. The worldwide decline of ginkgoes that began before the end of the Mesozoic and continued until 1000 years ago (when humans “adopted” the tree) seemed to result in a decline in the insects that depended on ginkgo. No insects specializing on ginkgo seemed to have survived to modern times. Additionally, ginkgoes have no fungal pathogens on record.

GINKGO AND HUMAN CULTURE

What does the name “Ginkgo” mean?

Peter Crane devotes an entire chapter of his book, Ginkgo: The Tree That Time Forgot, to the ginkgo’s naming. Two of the Chinese names for ginkgo translate to “silver apricot” (for the “fruit”) or “duck’s foot” (for the leaf). The Chinese characters are pronounced as “yajiao” or “yinxin.” The botanist Englebert Kaempfer, the first European to write about ginkgo, first encountered the tree in Japan, where ginkgo had been brought by people a thousand years earlier. The migration of ginkgo from Japan is believed to include the migration of the Chinese symbols for ginkgo, but the name’s pronunciation seems to have transformed when it was translated into Japanese characters. Two Japanese pictorial dictionaries in use when Kaempfer was in Japan provide “ginkyo” as the pronunciation. The switch of the “g” for the “y” by Kaempfer is a bit of a mystery. Some think it was a misspelling by Kaempfer, while others suggest that it was intentional, following the pronunciation of his particular dialect of German. From Kaempfer’s writings, “Ginkgo” was then recognized as the official genus by the foremost taxonomist at the time, Carl Linnaeus, and that name has been used as the genus and English common name ever since.

Can humans eat ginkgo fruit? Are dangerous compounds in the seed covering or the seed itself? Does it stink while preparing it?

Can humans eat ginkgo fruit? Are dangerous compounds in the seed covering or the seed itself? Does it stink while preparing it?

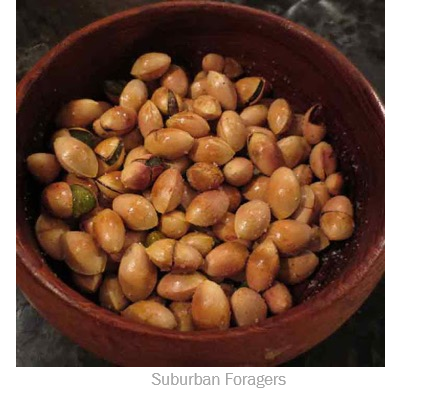

Yes, ginkgo nuts are edible and used in various Asian dishes. Be cautious not to eat too many as they contain a toxic substance even after cooking. The sarcotesta, the seed’s fleshy outer covering, contains one or more chemicals that can cause a skin rash similar to poison ivy. The seed contains the chemical methoxypyridoxine, which inhibits the production of vitamin B6 and can result in seizures, convulsions, and death.

A ginkgo nut has a sweet, tangy (slightly bitter) flavor with a chestnut-like texture; some say it has the undertone of its odor. Cleaning ginkgo seeds is easy and quick, so you do not have to put up with the odor for very long. Wear gloves!

In the unfortunate event of a blight, are seeds being harvested and stored to replant in the future?

There are over 1700 seed banks in the world, so it is safe to assume that ginkgo seeds, which withstand drying and freezing, have been stored in one of these banks.

GROWING AND CULTIVATING GINKGO

Are ginkgoes easy to grow? Do they grow better near or apart from other trees? What variety do you recommend for a backyard?

The ginkgo is incredibly easy to grow! It is very resistant to insects and diseases and requires only sunlight and well-drained soil. Ginkgoes do best in full sun and can grow to be very large, so it is best to give them plenty of room. Ginkgoes get big! The ginkgo is not listed as tolerant of black walnut, although unconfirmed sources say it is. There are quite a few cultivars available on the market, but some are hard to find. “Autumn Gold” is widely available and considered one of the best.

Are there ordinances that prohibit planting female gingkoes? Is it OK to spray them to curb the smell? Is there a way to clean up the fruit?

Some municipalities apply plant growth regulators on female ginkgoes, but it is only partially effective. Some cities have concluded it is less expensive to remove female ginkgoes than to spray them, and some have banned planting females altogether. Most nurseries now sell only male trees, so this problem is becoming less common. Ginkgo fruit quickly becomes soft once it falls to the ground, so raking it is not feasible. Once the temperature drops, the smell seems to reduce. At Blandy, we just let the fruit decompose.

Do you need both male and female plants to have a healthy ginkgo?

No, an individual ginkgo tree will be healthy and vigorous without a member of the opposite sex nearby. A nearby male is needed to provide pollen to a female to produce the ginkgo “fruit,” but if a female is not pollinated, that won’t affect her health. She simply will fail to produce fruit. Male ginkgoes produce a tremendous amount of pollen, and the pollen can be carried substantial distances on the wind, so a female might be able to produce fruit even if the nearest male is more than a hundred yards away.

How do I grow a ginkgo from seed?

It is not difficult to propagate a ginkgo from seed. Clean the seed, place it in a small plastic bag filled with slightly damp potting soil, and put it (closed) in a warm location for 1-2 months. Then, refrigerate the bag for 1-2 months. Plant seeds in well-drained potting soil. Germination can take 8-10 weeks. One word of caution: You have a 50% chance of producing a female tree.

Are the ginkgoes commercially available in the U.S. hybrids or the original variety found in China?

Most of the trees you will buy at nurseries today are cultivars of the original trees. They are usually a type found in the natural population that is slightly different than growers feel would appeal to the landscape market. These are then asexually propagated to maintain desirable characteristics.

Are the males chosen by cloning or cuttings?

Cuttings are clones since the genetic material of the offspring is identical to the parent. Male ginkgoes are produced by rooting cuttings taken from male trees and by grafting, using the male bud as the scion. The female ginkgo may be used as the rootstock.

Is a weeping gingko grafted onto another stock tree?

Yes. The weeping forms of ginkgo are unstable and cannot be reproduced sexually from seed. Therefore, they have to be produced by an asexual method (grafting).

Is there any concern about the longevity of the species if humans prefer not to plant females?

There are female producing ginkgo trees cultivated all over the world. Because there is a high demand for nuts for culinary and medicinal purposes, the female trees are still propagated and planted. The male tree’s popularity is in the landscaping / horticulture areas. The female tree is often used for the rootstock when ginkgo trees are grafted.

Given the catastrophic collapse of insects and birds during the past 40 years, should we be planting as many ginkgoes as we have been doing in North America?

Important point. Blandy strongly advocates planting native species of trees and shrubs for the benefit of wildlife. Native trees host large, diverse communities of native insects, which, in turn, are vital food sources for birds. Exotic plants are simply no substitute, and ginkgoes do an especially poor job supporting insects. There are, however, locales where a species like the ginkgo makes sense. Ginkgoes are highly resistant to air pollution and other stresses of the urban environment and make an excellent tree for lining urban streets. Although they have limited (at best) wildlife value, they do sequester carbon, and their shade helps reduce the urban heat island effect in an environment where few other trees can thrive.

“Pratt ginkgo” turning green to gold outside UVA’s Rotunda. Photographed 11/14/2020. Courtesy of ML Musser

“Pratt ginkgo” turning green to gold outside UVA’s Rotunda. Photographed 11/14/2020. Courtesy of ML Musser

Do ginkgo trees grow in the high desert (Zone 9A)? In Maine? In the U.K.?

Some references say ginkgoes will survive through Zone 8; others say Zone 9. Ginkgoes survive in Southern Maine and are found in the U.K. The website The Ginkgo Pages has locations and photos of ginkgo trees all over Europe. After ginkgoes were introduced in England in the mid-1700’s, they became a popular landscaping tree in Europe and the United States.

At UVA’s Fontaine Research Park in Charlottesville, how did a female ginkgo sneak into the landscape?

Fontaine Research Park was built in the 1990s. There were still nurseries then that sold ginkgo trees grown from seed (outcome: resulting tree could be male or female). Also, grafted ginkgo trees can sometimes have the graft fail, which may go unnoticed by the nursery grower. Consequently, the rootstock, which, in many circumstances, is female, will sprout, resulting in a female tree.

THE BLANDY GINKGO GROVE

How many Ginkgo trees are in the grove?

There are about 300 trees in Blandy’s Ginkgo Grove.

Why are the trees with double trunks at the edge of Blandy’s Ginkgo Grove “copsed”?

We have never pruned any of our ginkgo trees unless it was to repair storm damage. We have lost quite a few leaders out of our ginkgoes during storms. We have also had large limbs that were heavily laden with fruit break off.

Is it possible to have one’s ashes spread in the Ginkgo Grove?

We have a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy about spreading ashes at Blandy.

On a different note, what is happening with the cedars of Lebanon at Blandy?

Sadly, it appears that the cedars of Lebanon at Blandy are succumbing to human pests. First, they need abundant sunshine. The inner row of trees is between the oaks and the second row of cedars is now nearly in complete shade. The road between the two rows was widened years ago, and Blandy visitors drive over and park on the trees’ roots daily. Soil compaction is deadly to cedars of Lebanon.

What is something new the Blandy ginkgo experts have learned about theses ancient trees?

There is still much to learn about ginkgoes. Recent research at Blandy includes: sex changing in ginkgoes (most trees stay either male or female for their entire life, but a few switch); modern insects that feed on ginkgo (very, very few); and ginkgo response to elevated levels of carbon dioxide (ginkgoes evolved when CO2 levels were higher than they are today).

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Vietnam: J-Term Farewell Social

- UVA Club of Atlanta: UVA Women's Basketball at Georgia Tech