The Jewish Grandchildren of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson

“Origins are not destiny,” writes James Loeffler, considering how the past can shape the next chapter of American history. Loeffler is the Jay Berkowitz Professor of Jewish History in the Corcoran Department of History and the Ida and Nathan Kolodiz Director of Jewish Studies in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia.

“Origins are not destiny,” writes James Loeffler, considering how the past can shape the next chapter of American history. Loeffler is the Jay Berkowitz Professor of Jewish History in the Corcoran Department of History and the Ida and Nathan Kolodiz Director of Jewish Studies in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia.

The Jewish Grandchildren of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson

What can Charlottesville’s forgotten Jewish past teach us about the American struggle for freedom?

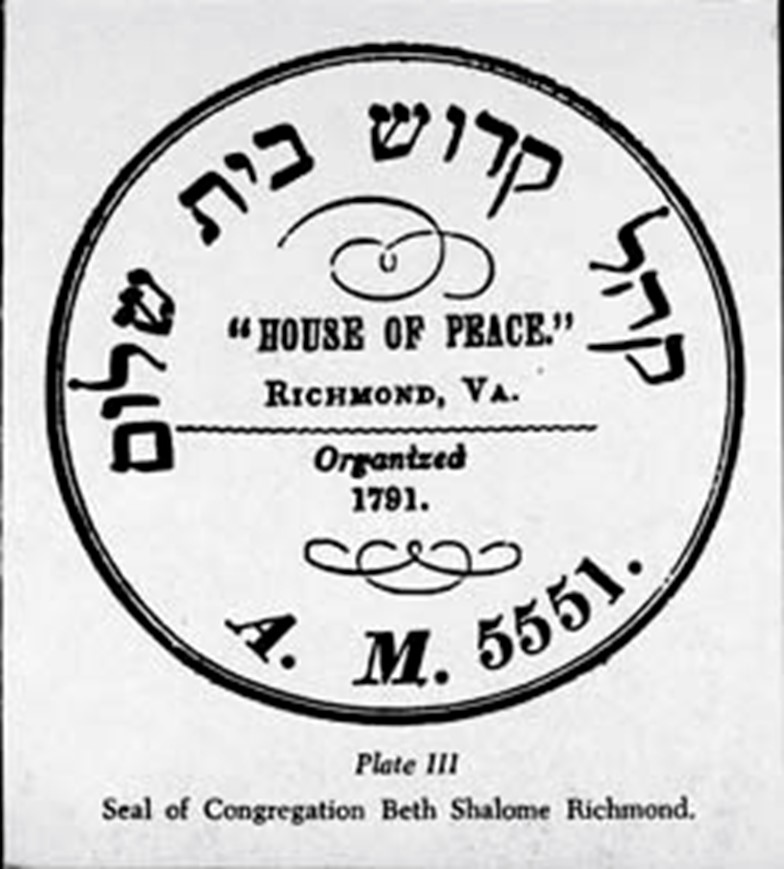

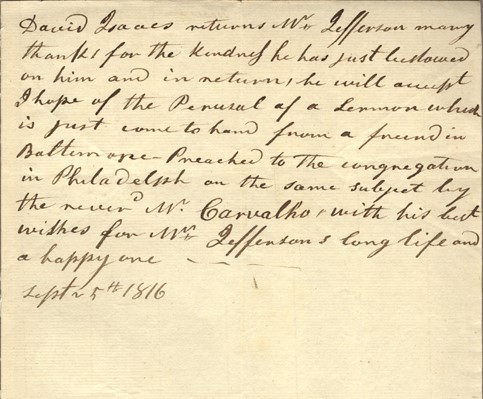

On October 11, 1822, an Albemarle County Court grand jury voted to indict Charlottesville residents David Isaacs and Nancy West for the crime of “umbraging the decency of society and violating the laws of the land by cohabitating together in a state of illicit commerce as man and wife.” David was a Jewish immigrant from Germany who ran the town’s general store. For his religious community, he traveled back and forth to the Beth Shalome synagogue in Richmond. Nancy was a free mixed-race woman who owned local property, ran a bakery, and launched one of the country’s first African-American newspapers. Together, they raised seven children as common-law husband and wife in the heart of downtown Charlottesville. Their lives passed without incident until the day they were hauled into court to face criminal prosecution for interracial miscegenation.

Every time I teach this story in my undergraduate course on American Jewish history, students respond with a litany of questions, many of which echo contemporary concerns about race and religion in American society. Were David’s and Nancy’s children considered Black or white? Jewish or Christian? Did anti-Jewish prejudice play a role in this episode, or was the persecution motivated only by color-based racism? What, exactly, was the alleged crime? That last question draws out the future lawyers in the class, who invariably spot a legal problem: Since the couple never formally married in civil court or via Jewish religious ceremony, how could they even be accused of an illegal marriage?

When we interrogate the past, we find clues to the present. Today, many people ask why white supremacists target Jewish communities largely comprised of white-skinned Jews. One answer is that race and religion often fuse together in the antisemitic imagination, producing depictions of Jews as pseudo-white, anti-Christian racial imposters. Another contributing factor is the long, shared American history of these two very different minority communities. When David Isaacs reached across the color line to partner in life with a mixed-race woman, he prefigured an enduring pattern of close contacts between Jews and African Americans in the realms of American social life, urban commerce, popular culture, and civil rights activism. Over time, those associations bred antisemitic images of Jews as dangerous agents of interracialism.

Yet the study of history also cautions us against over-generalization when it comes to the politics of race and religion, even for America’s minority communities. David Isaacs clearly rejected slavery and openly embraced his interracial family. But his brother Isaiah, who lived in Richmond and co-founded the city’s Beth Shalome congregation, owned slaves. That two brothers who worshipped together could split on the ethics of slavery reminds us that religion and morality have never correlated as neatly as we might wish to imagine.

The more we can see these complex, intertwined legacies of race and religion, the better equipped we will be to make informed choices about the challenges that confront our democracy today. That is one of the aims of the University of Virginia Jewish Studies Program, where our faculty teach students how to navigate the difficult past and interpret the perplexing present. Part of this process involves recovering the forgotten stories of Jewish life in Charlottesville and Virginia, work pioneered by my History colleague *Phyllis Leffler. Our work also extends across many fields and disciplines to subjects as diverse as the Holocaust and human rights, Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations, immigrant literature, and religious ethics. In each of these areas, we emphasize that even as the past shapes our present, it cannot lay claim to our future.

Nothing illustrates that better than the strange twists in the saga of Nancy West and David Isaacs. In 1827, after five years of court battles, the charges were finally dropped against the couple. Life returned to normal. The children grew up. Then daughter Julia Ann married a local man named Eston Hemings. The son of Sally Hemings, he had recently been freed from slavery after the death of his father, Thomas Jefferson. Yet the story did not end there. Eston and Julia Ann later moved to the Midwest, where they assumed the surname “Jefferson,” and began to identify publicly as Jefferson’s white, Christian descendants.

These kinds of contradictions are woven into the fabric of American democracy. Recalling them is a painful yet necessary part of understanding how we have arrived at our own moment of crisis. Still, historical reckoning does not mean we cannot find succor and even inspiration in the past. The story of Nancy West and David Isaacs and their descendants contains within it a small but invaluable truth. Origins are not destiny. It is as individuals that we ultimately author our own lives. That lesson can embolden us to imagine new stories for ourselves and our world. In doing so, we begin to write the next chapter of American history.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party