The Wonder of Fall Migration

David Carr, director of UVA’s Blandy Experimental Farm and State Arboretum of Virginia, presented a virtual lecture on autumn migration sponsored by Lifetime Learning in October 2020. Carr, a research professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Virginia, answers questions (below) that were posted from an enthusiastic audience of bird watchers during the program.

Photo: Joe Alderman

What factors contribute to the population decline of migrating birds?

A very important question. Habitat loss/degradation in the breeding area, wintering area, and in critical stopover points in between is probably at the top of the list. A recent study on bird population losses in North America identified birds of grassland habitats as showing the steepest declines. Birds that breed in boreal forests were second. A closely related factor, and one that will likely become increasingly important, is climate change. This will be especially important for Arctic and boreal forest breeders, but we will likely see effects here in Virginia during our lifetimes. For example, some of the highest mountains in Virginia still have boreal forest at their tops, and these provide habitats for species that normally breed much further north. With warming temperatures, these habitats will eventually disappear from the Commonwealth. On Virginia’s coast, rising sea level is reducing the extent of marshes faster than they are regenerating, creating habitat loss for many marsh nesting species.

Other sources of mortality include collisions with buildings, radio and TV antennas, and yes, even wind turbines. Outdoor house cats are also blamed for huge numbers of bird deaths, but these probably represent a secondary threat relative to habitat loss and climate change.

What are the predominant bird types/species that migrate to/from Virginia?

The neotropical migrants (birds that breed in the US or Canada but winter in Mexico or south to South America) represent the largest group of Virginia migratory birds. These include waterfowl, nightjars, hummingbirds, swifts, cuckoos, rails, grebes, herons, hawks, and falcons, but the biggest groups of neotropical migrants are the shorebirds (over 50 species) and songbirds (well over 100 species).

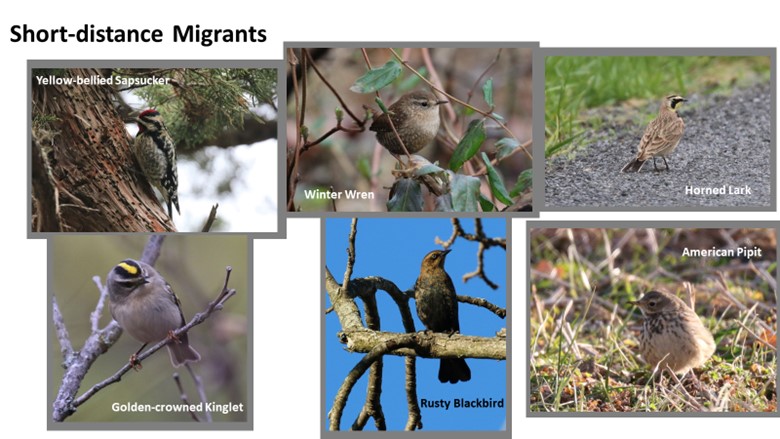

Neotropical migrants are not the only migrants in Virginia. Many species of birds move from Canada to the southern US each year. In addition to some of the groups I mentioned above, these shorter distance migrants include loons, owls, and a few woodpeckers. Important groups of songbirds in this category of migrants include sparrows, finches, larks, pipits, and blackbirds.

Even some birds that we think of as year-round residents in Virginia migrate. For example, at any time of year you can find red-tailed hawks, blue jays, or eastern bluebirds almost anywhere in Virginia, but some of our summer residents of these species move further south in the winter, and they might be replaced with migrants from further north.

Does Virginia have bird migration patterns that are unique from other states?

That’s an interesting question. Migration patterns vary a lot from east to west and from north to south. Virginia, which straddles the north and south, is at the northern limit of some of the more southern birds and at the southern limit of some of the more northern migrants. Another relatively unique aspect of Virginia is that it spans from the Atlantic Ocean to the Appalachian Mountains and Cumberland Plateau. The mountains and coast represent distinct important flyways, with some species favoring the coast and others the mountains. Virginia has the best of both worlds that way. The tip of the Delmarva Peninsula also generates a fairly unique migration feature. As southbound birds travel down the Eastern Shore, they are funneled into the Kiptopeke area before they cross the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, creating a concentration point for migration. It makes Kiptopeke State Park one of the best places in Virginia for fall migration.

How has climate change impacted migratory patterns?

This is a critical question for bird conservation. For many (if not most) migrating bird species, the timing of migration is closely tied to day length, which of course is unaffected by climate change. Bud break and insect emergence, however, are affected by a combination of day length and local temperatures. Migration places extreme energetic demands on birds, and their migration routes and behaviors have evolved to take advantage of the emergence of food resources along their migratory routes. Timing is critical, and climate change threatens to disrupt that timing. There is already evidence that the arrival of spring migrating birds has advanced over the past half century, but it is unknown if this shift in timing is helping to maintain the relationships between birds and their food resources.

One migration/climate change observation that I have made here at Blandy (thanks to a volunteer group that monitors over 100 bluebird boxes), is that tree swallows are arriving and starting to nest a week earlier than they did 20 years ago. Eastern bluebirds, which are mostly year-round residents here, have not changed the date when they begin nesting. Our bluebird box monitors have noted a very strong shift in box occupancy during that 20 years, with a greater percentage of the boxes now occupied by tree swallows than bluebirds. I believe that the earlier arrival of the tree swallows is giving them a competitive advantage for those boxes.

Is there a single, most important factor that determines whether an individual bird species migrates or not?

Migrants from the tropics are clearly responding to the explosion of invertebrate activity (everything from insects and spiders to zooplankton) in the temperate part of the Northern Hemisphere. These invertebrates represent an enormous protein resource for migrants and their babies. These birds retreat to the tropics as the invertebrates disappear with the colder temperatures in the fall.

That said, many species of tropical birds do not migrate north in the spring. They spend their entire lives in the tropics despite having close relatives that make the long journey back and forth every year. For example, there are about 50 species of warblers (family Parulidae) that migrate into the US and Canada from the tropics each year, but an approximately equal number do not. The question of why one species of warbler migrates and another does not is much harder to answer (but certainly worth asking).

Even for birds that are not migrating from the tropics, the ultimate reason for their migration probably boils down to food. Whether it’s a long-eared owl that breeds in the boreal forest of Canada or a snow bunting on the Alaskan tundra, winter means snow, cold temperatures, and less food, so their prospects for survival are better further south during those months.

What can people do to assist birds as they migrate?

Anything you can do to provide food for birds will help migrants. This include bird feeders (thistle feeders, sunflower feeders, suet feeders, and hummingbird feeders), but it also includes landscaping your yard with appropriate plants. Plant species that are native to your area are the best choices because these species will support more native insects that provide a key resource for migrating birds, especially songbirds. A recent book by Doug Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home, is an excellent resource in which to find species that are particularly helpful because it has recommendations for different regions of the country. Your local native plant society (the Virginia Native Plant Society is headquartered at Blandy, by the way) is also a good source. The plants not only provide valuable insect food, they provide the cover they need from would-be predators, and many plants also provide fruit and seeds that many migrants eat along their journey.

In addition to feeding birds, there are many worthy organizations that work to conserve habitat or conduct research to increase our understanding of migrating birds. Supporting them is an excellent way to be part of the solution.

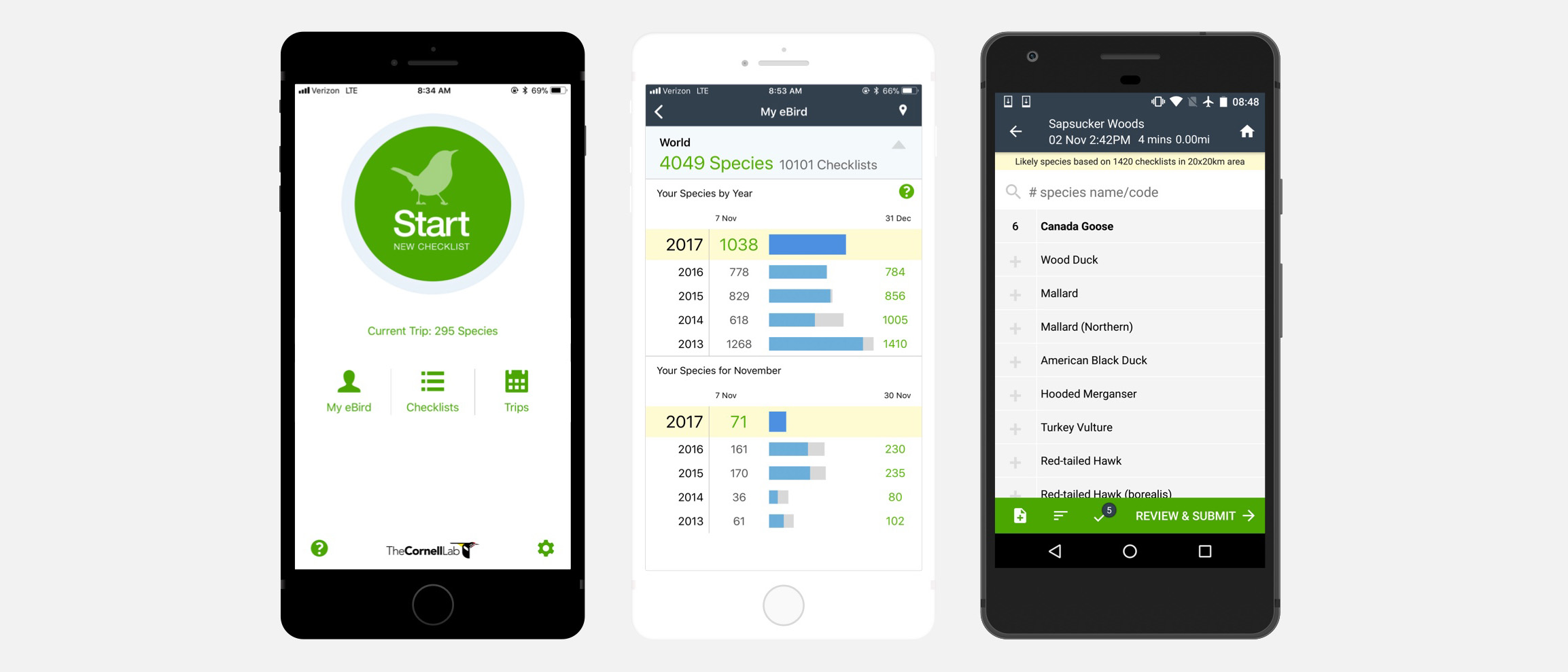

You can also become a citizen scientist and increase our understanding of how birds are doing. Contributing your sightings to eBird, a free online database operated by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, helps grow what has quickly become one of the most valuable resources on the timing and distribution of migrations. Look for opportunities to participate in Christmas Bird Counts in your area, one of the longest-running citizen science projects in the world.

What resources do you recommend for bird watching and tracking bird migration patterns?

There are many good field guides. I think the best book for beginners is the Peterson Field Guide to the Birds (there are versions for the Eastern and Western US as well as the whole country). I think the best book overall is The Sibley Guide to Birds (again, East, West, and whole country versions are available), but it can be a bit overwhelming for a beginner. Both of these books have corresponding apps that you can use from your smart phone. Two other apps that I use are the iBird Pro Guide to Birds and the Audubon app.

There are many good field guides. I think the best book for beginners is the Peterson Field Guide to the Birds (there are versions for the Eastern and Western US as well as the whole country). I think the best book overall is The Sibley Guide to Birds (again, East, West, and whole country versions are available), but it can be a bit overwhelming for a beginner. Both of these books have corresponding apps that you can use from your smart phone. Two other apps that I use are the iBird Pro Guide to Birds and the Audubon app.

Another useful app (not a classic field guide) is the Merlin app produced by Cornell. It asks you a series of questions that help you narrow the possibilities. You can also feed photos into the Merlin app, and it uses an artificial intelligence algorithm to identify the photo. It is amazingly good, even on relatively poor photos.

Useful resources for tracking migration include the BirdCast website, which taps into weather radar to give you a live view of migration patterns and has a model that tries to predict migration patterns 24 hours in advance. I also use eBird to track migration. Through eBird you can search by states, counties, or even “eBird hotspots” to find out what people are seeing, and there are updates in real time. You can also do searches by species to find where a given species is currently being seen. For example, I have been following a mass movement of evening grosbeaks from Canada into the United States over the past week. Over the weekend there were many sightings in Pennsylvania, and I am looking for them now here in northern Virginia.

How has COVID impacted long-term research projects of migrating birds?

As the director of a field station, I know that our research capacity was greatly curtailed by the pandemic. Housing people safely was one of our biggest challenges, and we had to keep densities much lower than we would have during a normal field season. To accomplish this, we had to tell many researchers not to come to Blandy last summer. Because many of the long-term studies on birds are done at field stations, many were likely in the same boat. You can read an article from Audubon about the problem here.

Do birds know if they don’t have enough fat and does it affect their migratory behavior?

“Know” might be a loaded term, but yes, bird feeding and migratory behavior is very dependent on their body condition and fat reserves. At least their bodies “know.” For example, red knots (long-distance migrating shorebirds) arrive in the Delaware Bay weighing an average of about 110 grams. The birds refuel on horseshoe crab eggs during the stopover. Birds weighing below 130 grams first will rebuild muscle until they reach 130 grams. Once they reach that threshold, their body switches to converting food into fat. The red knots continue feeding until they reach 180 grams, packing on 50 grams of fat before moving on to the Arctic. Red knots arriving in the Delaware Bay seem to be aware of both their body condition and the calendar. Birds will adjust their feeding rates accordingly, feeding at higher rates and putting on fat faster as the departure date approaches, and feeding at higher rates the further they are from the optimal 180 grams. Birds that are unable to attain a body mass of 180 grams might still try to migrate if the calendar enters June, but banding data suggests that they are much less likely to survive to the following year.

Do birds change their songs with the seasons?

Yes. Most of our songbirds stop singing altogether by late July or early August (there are many exceptions, however), but the frequency, timing, and even the quality of the song can change throughout the breeding season. Most of this is controlled by day length effects on hormone levels in the blood, which in turn affect the bird’s brain. The changes in songs may reflect a change in the function of the song.

In Savannah sparrows, for example, males sing mostly at dawn when they arrive on their breeding grounds, and their songs appear to be directed at other males and the establishment of territorial boundaries. Later, when females arrive (males in many migrating species arrive before females), most of the singing switches to dusk and seems directed at attracting a mate and mate guarding. Many warblers have variations in their songs that are sung at different times of day.

How have you seen the habitats and bird communities at Blandy Farm change in the time you have been there?

At Blandy specifically, habitats have changed, and birds have changed along with them. Most of the habitat change at Blandy has come from fallow fields becoming increasingly wooded, resulting in a shift from grassland species (e.g., grasshopper and field sparrows, Eastern meadowlarks, and red-winged blackbirds) to species that prefer shrubby areas (e.g., willow flycatchers, gray catbirds, brown thrashers, and orchard orioles). Blandy is such a mosaic of habitats, though, that the overall diversity of birds has remained mostly unchanged since I arrived 23 years ago. Habitat and bird diversity changes have been more dramatic in nearby Frederick County. For example, farmland in Frederick County has gradually been converted to suburban neighborhoods where bird diversity has dropped, and communities have shifted to species more at home in habitats offered by the suburbs. Our local annual Christmas Bird Count straddles Clarke and Frederick counties, and groups who cover areas in Frederick County tell me that birds are much harder to come by for them. The pattern in Frederick County is probably mirrored in many of the suburban counties throughout the Commonwealth. Clarke, on the other hand, has seen much less development over the past two decades and bird diversity here remains relatively high.

Have correlation studies been done that tie migration timing to winter weather severity?

Seasonal changes in daylength have more to do with migration timing than winter weather for most of the neotropical migrants that I talked about in my presentation. However, migration in many other species seems much more sensitive to winter weather. Waterfowl migration seems to be strongly affected by the timing of freezing weather in the north, with big influxes of ducks, loons, and grebes as lakes being to freeze in Canada and the northern US. Here in Virginia, some of our most exciting winters with migrating waterfowl happen when the Great Lakes freeze. Some songbirds are strongly influenced by winter weather. Horned larks, Lapland longspurs, and snow buntings are ground feeding birds, and they get pushed further south as snow covers the fields they depend on. The irruptive finches that I mentioned in my talk (pine siskins, purple finches, red and white-winged crossbills, common redpolls, and evening grosbeaks) seem less affected by the severity of the winter than the abundance of the cone crop in Canada and the northern US, but severe winter weather can push these species further south even in years of good crops. The 2020 invasion of these irruptive species is reaching historic proportions this fall.

How have you recorded all the birds you have spotted, and what is one bird you would like to add to your “life list”?

A fun question. I began “life-listing” and have written records of bird sightings dating back to 1981. I resisted for a couple of years when I started birding because I was afraid listing would cause me to care only about birds I hadn’t seen. I have not regretted giving in to the listing bug, however. I have kept annual lists, and lists from individual birding trips that I have taken. I have also kept a master life list. In 2011, I started using eBird (which was relatively new at the time), and this has become my primary recording tool. I have not transferred all of my old records to eBird, but that might be a project when I retire.

Although I have birded in other countries, most of my travel is in the US and Canada, so my “North American” life-list is the one I obsess over more than any other. It stands at 702, and it has become hard to add species to it (my last addition was Gunnison sage-grouse in April 2019). The North American bird that I would most like to add is the whiskered auklet, a tiny seabird (about the size of a starling) that lives its entire life in the Aleutian Islands. It is a beautiful bird, and the idea of being on a boat far out in the Aleutian archipelago is extremely romantic to me.

Life-listing can be done on any scale. I now keep a life-list for every state and for every county (eBird makes this easy). Next to my North American list, my most prized lists are the one for Blandy (I’ve seen 214 species here) and the one for my yard at my place in West Virginia (151).

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Phoenix: Hoo-liday Party