Thomas Jefferson, Land, and Liberty

Land ownership was important to Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of “equal citizenship,” and he looked westward for new frontiers. John Ragosta, a historian at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello and lead faculty of the Virtual Summer Jefferson Symposium 2020 presented by the University of Virginia‘s Lifetime Learning, looks at how Jefferson saw land “as a central building block of the new nation.”

Land ownership was important to Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of “equal citizenship,” and he looked westward for new frontiers. John Ragosta, a historian at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello and lead faculty of the Virtual Summer Jefferson Symposium 2020 presented by the University of Virginia‘s Lifetime Learning, looks at how Jefferson saw land “as a central building block of the new nation.”

Virtual Summer Jefferson Symposium will be held from June 23-26, 2020 (sold out). We welcome your comments below.

Thomas Jefferson’s front hall, for those few who have not been to Monticello, was full of memorabilia from the West. The large room had a fine collection of Native American weapons and pottery. A buffalo-hide painting of a historic battle between the Mandan and Sioux nations and their allies also hung there. Antlers from elk, mountain sheep, and antelope adorned the walls. Mastodon bones from Kentucky were set for viewing. There were objects from elsewhere, but the West predominated. Much of the collection originated with the Lewis & Clark expedition but remembering that epic journey was not the primary purpose for the display. The collection as a whole seemed to draw the viewer west.

There is some oddity in this. Jefferson never traveled west of the Shenandoah Valley, but he was fascinated by the West, both the land and the concept, the idea that there were frontiers yet to be “conquered” and, importantly, incorporated into the still-new United States. The great Jefferson scholar Merrill Peterson wrote of the sage of Monticello that “among the Founding Fathers…no one more closely identified himself with the spirit and aspirations of the West or over a long career contributed as much to its growth and development.” Joseph Ellis declared simply that “in spirit, if not in fact” Jefferson was “a westerner.”

What was it about the West that not only fascinated Jefferson but engaged his vision?

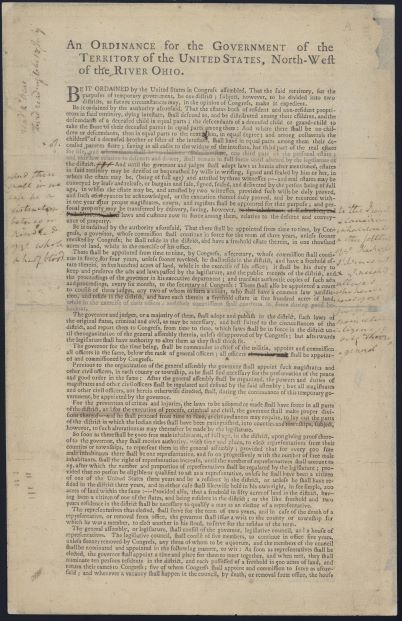

Jefferson’s westward tilt was long-standing. In 1784, as a member of the Confederation Congress, he created the first draft of an ordinance for settling the United States’ new western territory; many of the key provisions from his draft would be incorporated in the 1787 North West Ordinance. In his first inaugural address in 1801, he spoke of the United States having “room enough for our descendants to the thousandth and thousandth generation,” and this before his Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country in 1803. Of course, Jefferson was wildly wrong in his generational prediction, but it was clear that he was already looking west for national expansion, even national unity. A nation of westerners – small, independent, land-owning yeoman farmers – fed his natural optimism. (While Jefferson insisted that Native Americans must be paid for any land acquisitions, he also expected Natives to assimilate as farmers themselves–or continue being pushed further and further west.)

Jefferson’s support for yeoman farmers is well-known; in his Notes on the State of Virginia he declared that “[t]hose who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people…” In shorthand, we tend to attribute his patronage of yeomen to their independence: Owning their own land and relatively self-sufficient, yeoman farmers could be counted on to make independent electoral decisions, uninfluenced by any aristocracy, playing a crucial role in preserving the nation. This was a critical element and has been incorporated in an almost mythical devotion to yeoman farmers as a cornerstone of American exceptionalism. But Jefferson had much more on his mind when he promoted small independent farmers and saw the nation’s future in their westward trek.

First, American land was, truly, an American comparative advantage. In an era when Adam Smith was promoting that idea as central to the “wealth of nations,” Jefferson understood land–and its productive use–as a national economic resource. He understood that yeoman farmers would not be removed from an economic market, but would themselves help to create economic power. Having seen the role of tenant farmers in France, he warned a European correspondent that they had no incentive to improve the land. American yeoman would not simply produce real wealth, but literally invest in improving their own land, investing in the nation.

Broad ownership of land would also contribute importantly to Jefferson’s ideal of “equal citizenship” (at least for the white men who often seemed to limit his sight). Among an American people who had historically accepted deference to their “betters,” broad land ownership would be a central prop for American political equality. Similarly, a nation of yeoman farmers would discourage the gross wealth disparities that Jefferson had seen in Europe, wealth disparities that he also understood could destroy the young republic.

At a more philosophical level, recognizing the challenge facing a nation with a vast geography and a diverse citizenship, Jefferson believed that yeomen would be critical to the development of a successful and integrated United States, playing a role in making “from many one” (E Pluribus Unum). Literally working in the land, the yeoman farmer would have a special attachment to his own community and, thereby, a special attachment to the stability and success of the nation. In fact, with Adam Smith, Jefferson questioned the commitment of merchants and bankers to the nation; their commitments to profit would find them supporting whoever (and whatever nation) could guarantee their wealth. Yeomen had an inescapable commitment to their own land. And that commitment would create a virtuous cycle of hard, honest work to improve the land, and with it the citizenry.

Contrary to many modern interpretations of the role of yeoman farmers, Jefferson’s vision was neither anti-commercial nor anti-state. The opposite was true: Yeomen would play a critical role in the expansion of American economic wealth and could only do so with a government committed to, and capable of protecting, westward expansion.

Today, of course, fewer and fewer Americans are land-owning farmers who improve the land. Yet the principles on which Jefferson’s commitment to yeoman farmers stood continue to shape an American myth, but a myth that grounds the nation.

These will be among the topics that we will be discussing at this year’s Virtual Summer Jefferson Symposium on Jefferson, Land, and Liberty. For those that will be joining us, we’ll look forward to the discussion. Let me suggest for all of us, though, that the next time we have the opportunity to wander through Monticello (which will hopefully be reopening soon), we give some additional thought to how Jefferson saw America’s vast land itself as a central building block of the new nation.

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Vietnam: J-Term Farewell Social

- UVA Club of Atlanta: UVA Women's Basketball at Georgia Tech