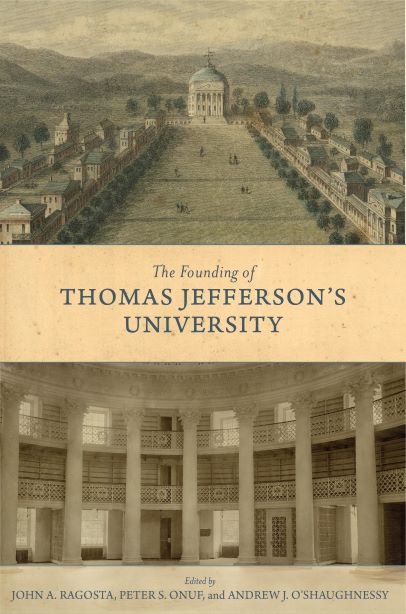

The Founding of Thomas Jefferson’s University

A conference celebrating the bicentennial of the founding of the University of Virginia was sponsored in May 2018 by the International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello in cooperation with the American Philosophical Society. The resulting book of essays, The Founding of Thomas Jefferson’s University (ed. by John A. Ragosta, Peter S. Onuf, Andrew J. O’Shaughnessy; University of Virginia Press, 2019), will be released in early September.

John Ragosta leads Lifetime Learning‘s Summer Jefferson Symposium and is a historian at Monticello’s Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies. Peter Onuf is UVA’s Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor, Emeritus. Andrew O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in UVA’s College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello.

The University Survives*

Preparing a volume of essays on the history of a university is an odd endeavor in some respects, not unlike writing a biography of a person who still lives. We can only write an introduction with anticipation of what is to come. The past is prologue, as Shakespeare quipped, but the “earth belongs … to the living,” the sage of Monticello assured us.

Still, Jefferson understood as much as anyone that the careful and honest study of history provides an essential platform from which to understand the present and plan for the future, no less so for a university and for the role of education in a republic. This volume and the conference on which it was based have been pursued in that spirit.

A collection of essays on the early history of the University of Virginia is, unsurprisingly, largely defined by the University’s founder, as was the school in its early years and to some extent still today. So much of what was unique and different at the University of Virginia in its design and youth came directly from Jefferson. Ralph Waldo Emerson once remarked: “An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.” Rarely has that statement been so true as in the case of the University of Virginia. Few, if any, universities owe so much to the vision of one man, and his spiritual presence in Charlottesville is inescapable.

A collection of essays on the early history of the University of Virginia is, unsurprisingly, largely defined by the University’s founder, as was the school in its early years and to some extent still today. So much of what was unique and different at the University of Virginia in its design and youth came directly from Jefferson. Ralph Waldo Emerson once remarked: “An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.” Rarely has that statement been so true as in the case of the University of Virginia. Few, if any, universities owe so much to the vision of one man, and his spiritual presence in Charlottesville is inescapable.

Undoubtedly there were important innovations at the University. Historians of education have long credited Jefferson and his University for helping to launch the movement toward an elective curriculum, now a foundation for higher education in the United States and around the world. The change has had truly revolutionary consequences. No less important was his determination to free education from the grips of religion and religious orthodoxy, an innovation that Jefferson pursued on a broader political landscape as well. Focusing more specifically, a look at medical education suggests marked improvements were made at the founding of the University of Virginia. Inquiries into other fields may yield similar discoveries.

Of course, academic papers on very particular aspects of the founding of the University of Virginia—from cataloguing books, to specifying which British jurists should be read for understanding the common law, to the whimsical possibility of using the inside of the Rotunda’s dome as a large easel for astronomy studies—should not hide the more fundamental point about why a university was being built and what it hoped to achieve.

Certainly, in the 1820s, Jefferson saw the University as a means to limit the spread of what he saw as pernicious northern and Federalist ideas, including immediate abolitionism, with which he believed too many Virginian and southern students were being infected at northern universities. At the time of the University’s construction, Jefferson was undoubtedly focused on protecting and promoting the interest of Virginia and its southern neighbors, a focus sharpened by the sectional crisis at the time of the Missouri Compromise—Jefferson’s “fire bell in the night.” He envisioned educating leaders for his state and nation, but southern leaders in particular. And time would show that many graduates of the University would play critical roles in the Confederate Army and government.

Yet, focusing solely on that result distorts Jefferson’s broad vision. Jefferson had been advocating the formation of a public university since at least 1779 and saw it as an important institution to provide the leadership necessary in a republic, a leadership that should promote the “natural aristocracy” of merit and protect the sinews of a representative republic. His unlikely alliance with Joseph C. Cabell in obtaining legislative approval for the University was driven by a mutual commitment to the benefits of education for the students and the nation and, equally important, for the development of knowledge and progress of mankind. The University’s legacy of slavery must be explored, understood, and confronted, but it is not the legacy that drove Jefferson’s initial commitment to a university, nor the one that he intended to leave.

Even beyond the critical advantages to be found in the pursuit of knowledge, Jefferson was deeply conscious of not just the role that higher education played in teaching a student facts and theories about biology, history, and philosophy, but also the role of the intimate interactions of students and mentors, young people exploring the universe and their own developing personhood with educators deeply interested in both. While he emphasized the fundamental flaws he found in the program at William and Mary at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century, he was always grateful for the broader education he received there. Jefferson first experienced the Enlightenment at Williamsburg, dedicating himself thereafter to the pursuit of truth, science, and progress—all in the name of humanity and on behalf of the community of other scholars and seekers. This was the source of his passionate commitment to constructing the University of Virginia, choosing its faculty, and implementing what he saw as important innovations, even his elaborate, detailed plans for organizing the library and controlling the circulation of books. It was these high hopes that left Jefferson so sad—literally tearful and speechless—in the wake of student riots. The University was his hope not just for Virginia, the South, and the nation, but ultimately for the ongoing progress of enlightenment everywhere.

We still believe that this is the mission of the University of Virginia. Today, students and graduates explore the frontiers of knowledge and dedicate themselves to serving their communities and the larger world. The breadth of the University’s reach alone speaks to the possibilities. In 1825, the University of Virginia opened with sixty-eight students, mostly sons of wealthy white planters, and eight faculty members. Today, almost 23,000 undergraduate and graduate students of every ethnicity, creed, color, and background join with over 3,000 faculty members in studies encompassing all realms of knowledge. Over 200,000 living alumni touch virtually all possible human pursuits around the diverse corners and byways of the world. The contributions of the University and its graduates are vast and expanding.

We still believe that this is the mission of the University of Virginia. Today, students and graduates explore the frontiers of knowledge and dedicate themselves to serving their communities and the larger world. The breadth of the University’s reach alone speaks to the possibilities. In 1825, the University of Virginia opened with sixty-eight students, mostly sons of wealthy white planters, and eight faculty members. Today, almost 23,000 undergraduate and graduate students of every ethnicity, creed, color, and background join with over 3,000 faculty members in studies encompassing all realms of knowledge. Over 200,000 living alumni touch virtually all possible human pursuits around the diverse corners and byways of the world. The contributions of the University and its graduates are vast and expanding.

The University “survives,” to adapt John Adams’s dying declaration about Jefferson on July 4, 1826, the day the two old friends died. The University survives, much as the Declaration of Independence and Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom survive. Each is a living organism with unbounded potential for the future. Our failing, and the failings of the founders of the nation and the University, do not define the future of enlightened possibilities available through education, democracy, and freedom of the mind. The construction, staffing, and curriculum at the early University of Virginia were designed with that in mind.

As he neared his death, Jefferson famously wrote a letter celebrating the coming fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. The sage of Monticello wrote,

[M]ay it be to the world … the Signal of arousing men to burst, the chains under which Monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings & security of self-government … the general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth that the mass of mankind has not been born, with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of god. These are grounds of hope for others. 1

The same could be said of the University.

* This essay is reprinted with the permission of the University of Virginia Press.

1. Jefferson to Roger C. Weightman, June 24, 1826, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-6179.

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Washington DC: December Book Club