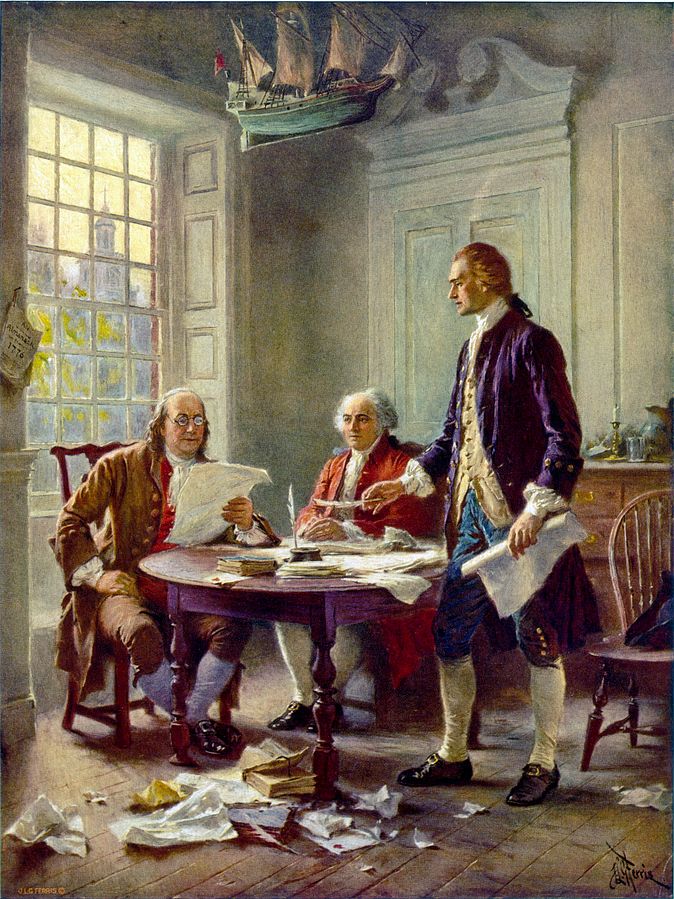

The Meeting of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and George III

Revolutions strain diplomatic relations, and Andrew O’Shaughnessy describes how the American Revolution was no exception. Mr. O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia and serves as Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. He was the first Sons of the American Revolution visiting fellow to the Georgian Programme at the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle and King’s College, London University.

Revolutions strain diplomatic relations, and Andrew O’Shaughnessy describes how the American Revolution was no exception. Mr. O’Shaughnessy is a professor in the Corcoran Department of History in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia and serves as Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. He was the first Sons of the American Revolution visiting fellow to the Georgian Programme at the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle and King’s College, London University.

The following is an extract from Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of the Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 17-19.

The Declaration of Independence casts George III as the leading villain of the American Revolution. It asserts that he was a prince whose character was “marked by every act which may define a Tyrant” and pronounces him “unfit to be the ruler of a free people.” As a member of the original committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence, John Adams later admitted that it contains “expressions which I would not have inserted, if I had drawn it up, particularly that which called the King tyrant.” Reminiscing at the age of eighty-eight, Adams thought it “too personal . . . too passionate, and too much like scolding, for so grave and solemn a document.” He confessed that he “never believed George to be a tyrant” or to be guilty of the “cruel” acts committed in the name of the King. In his autobiography, Adams was also critical of Benjamin Franklin for his “severe resentment” and personal animosity towards George III. According to Adams, regardless of the appropriateness of the occasion, Franklin never missed an opportunity to cast aspersions upon George III.

In one of the most incongruous and remarkable encounters between former adversaries, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson met George III after the American Revolution. The revolutionary leaders and the monarch, whom they had vilified, came face to face. As the first ambassador of the United States of America, Adams was presented to George III at St. James’s Palace in June 1785. It was an emotional encounter between an outspoken advocate of independence and a King who had considered abdicating rather than accepting the loss of America. Dressed in a black formal coat with silk breeches and a sash, Adams told the King that the meeting would form an epoch in the history of England and America. He said that he thought himself more fortunate than his fellow citizens in having the honor to be the first to stand in the royal presence in a diplomatic role. He hoped to be instrumental in restoring the old good nature and humor between people, who, though separated by an ocean and under different governments, had the same language and similar religion. He stressed the cultural ties that bound them, not the recent politics which had separated them. According to Adams, George III seemed much affected and answered with a tremor in his voice.

Assuming an air of familiarity, George III jested with John Adams that some people believed Adams was less attached than his fellow countrymen to France. Despite his surprise and embarrassment at what he thought an indiscreet comment, Adams attempted to match the royal humor replying that he had no attachment but to his country. “As quick as lightning,” George III responded that an honest man will never have any other loyalty. As was customary among royalty when giving the signal for a courtier to retire, the King then turned and bowed. In observance of royal protocol, Adams retreated by stepping backward and made his last bow at the door of the royal chamber. Accompanied back to his carriage by a royal official, Adams passed through the royal apartments where, at every stage, the serried ranks of servants, gentlemen-porters, and under-porters roared out like thunder, “Mr. Adams’ servants, Mr. Adams’ carriage.” Adams was delighted that his person, his status, and his country had been accorded respect and kindness beyond his expectations from the King. Adams and his wife Abigail subsequently became quite fond of George III.

In the summer of 1786, John Adams arranged an introduction of Thomas Jefferson, who was to receive a less civil reception than Adams from George III. At the time, Jefferson was not known as the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, an association that he did not promote until the rage of party politics in the 1790s. Unlike Adams, he was known to favor France over Britain in his capacity as the United States Ambassador to France. On the day of his presentation to George III, there was an unusually thin attendance at court, consisting of a few members of the royal family, government ministers, and foreign ambassadors. Other than an entry in his account book of the tips that he paid the porters at St. James’s Palace, Thomas Jefferson wrote nothing of the encounter at the time. Writing 35 years later in his autobiography, Jefferson was more forthcoming, relating how “it was impossible for anything to be more ungracious” than the notice that George III gave “Mr. Adams and myself.” He “saw, at once, that the ulcerations of mind in that quarter, left nothing to be expected on the subject of my attendance.” According to the grandson of John Adams, the King publicly insulted them both by turning his back upon Jefferson and Adams which “was not lost upon the circle of his subjects in attendance.”

Jefferson certainly never ceased to blame George III personally for the breakdown in relations leading to the American Revolution. Jefferson believed that, from the beginning of his reign, George III had schemed to impose a tyranny on America, writing that “future ages will scarce believe that the hardiness of one man adventured within the short compass of twelve years only, to build a blatant and undisguised tyranny.” After his return from London to Paris in August 1786, he wrote sardonically of George III as the American Messiah who had labored for twenty years to drive the nation to discover its own good and “who had not a friend on earth who would lament his loss so much and so long as I should.” For Jefferson, George III always would be the villain, the antagonist in America’s primordial narrative, its myth of origin. For Jefferson, this was not propaganda but objective truth.

Author’s note: The HBO 2008 mini-series John Adams reproduces the exact dialogue written by Adams to Secretary of State John Jay, 2 June, 1785. Read the first and second articles that contain this dialogue.

Also, read Mr. O’Shaughnessy’s article on the value of the manuscripts at the Royal Archives for the study of the American Revolution. Mr. O’Shaughnessy will co-lead Lifetime Learning‘s UVA at Oxford Seminar–The Old World and the New: Britain and America at Trinity College, University of Oxford from September 14-20, 2019 (sold out).

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party