Their Time, Our Time

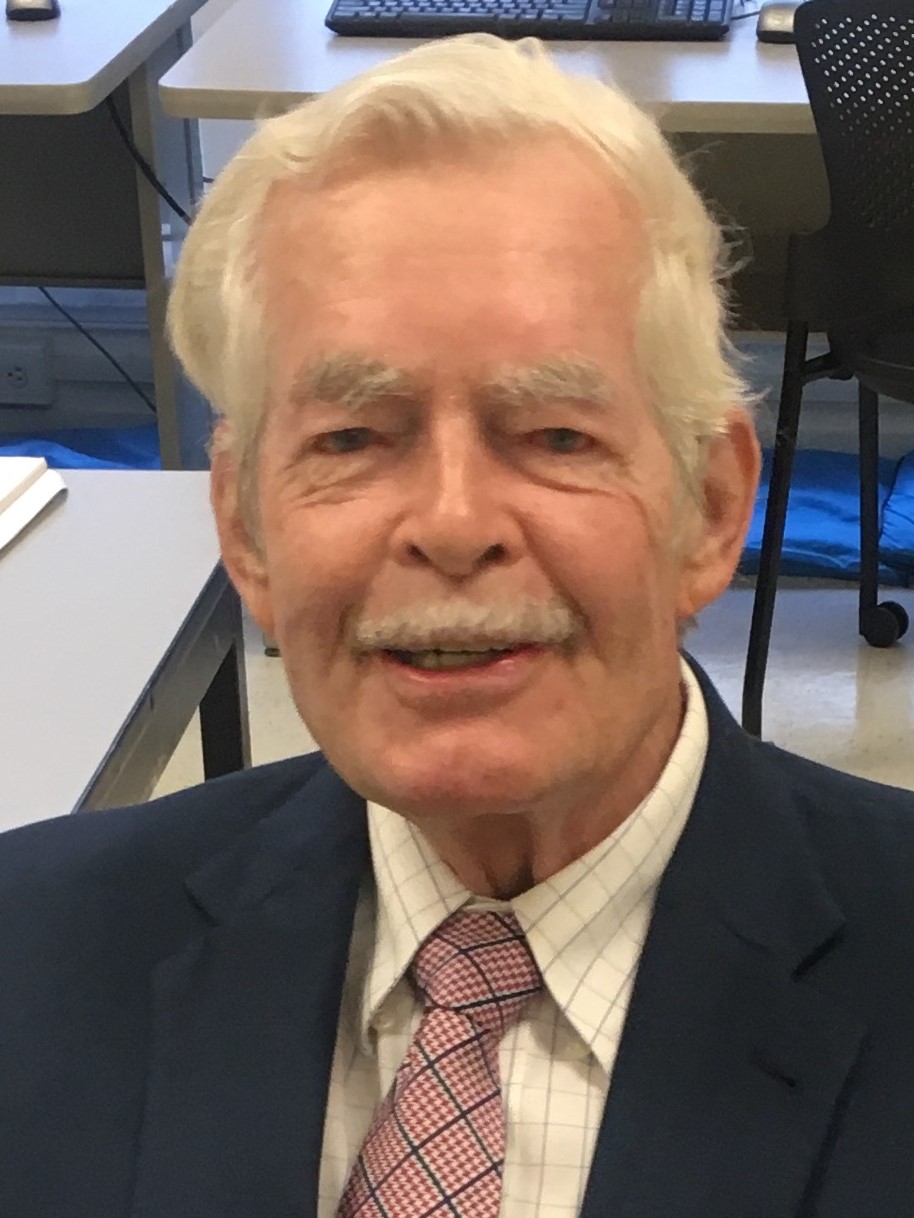

This Sunday, November 11, 2018 marks the World War I Armistice centennial, when guns on the Western Front fell silent. Mr. C. Brian Kelly gives us an interesting look at some of the key characters behind the first global war in his article “Their Time, Our Time.” Mr. Kelly is an assistant professor and teaches news writing in the Department of English in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia. He is the former editor of Military History and World War II magazines and is co-author of the book Best Little Stories from World War I with his wife, Ingrid Smyer (Col ’81).

This Sunday, November 11, 2018 marks the World War I Armistice centennial, when guns on the Western Front fell silent. Mr. C. Brian Kelly gives us an interesting look at some of the key characters behind the first global war in his article “Their Time, Our Time.” Mr. Kelly is an assistant professor and teaches news writing in the Department of English in the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia. He is the former editor of Military History and World War II magazines and is co-author of the book Best Little Stories from World War I with his wife, Ingrid Smyer (Col ’81).

Will the world again see a war on such a global scale? Please share your comments with us below.

Let’s all agree. As Armistice Day, now Veterans Day, rolls around yet again Sunday for the one hundredth time, we today are still asking, How could they? Looking back, we really do have to ask, how could they?

More to the point, what kind of crazy people?

Picture this: In 1901, England’s Queen Victoria is on her deathbed, a favorite grandson comforting her, his good arm under her as he assisted the doctor. His other arm was damaged at birth…perhaps like his brain.

And later, the same grandson is honored by Queen Victoria’s son and successor, King Edward VII… honored with appointment as a field marshal in the British Army. He then wore the marshal’s scarlet uniform to Edward’s own funeral in 1910.

Still later—would you believe, in June of 1914 itself!—he wore his British admiral’s uniform to the annual Kiel Regatta, attended by British King George V. He supped aboard a Royal Navy dreadnaught with the king.

Yes, in all these instances, the apparent Anglophile was Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, the same Germany that went to war against England and her Allies just two months after the Kiel Regatta.

Too bad, too, the Kaiser’s brother Henry, not too fluent in English, misunderstood King George V to say England would stay neutral in event of war. Too bad also the Kaiser may not have fully understood the British monarch did NOT make national policy.

Not to be left out of our scenario, Nicky, cousin to both George V and the Kaiser, pretty much was another ruler, as Czar Nicholas II of Russia, although he himself said, “I never wanted to become Czar, I know nothing of the business of ruling.”

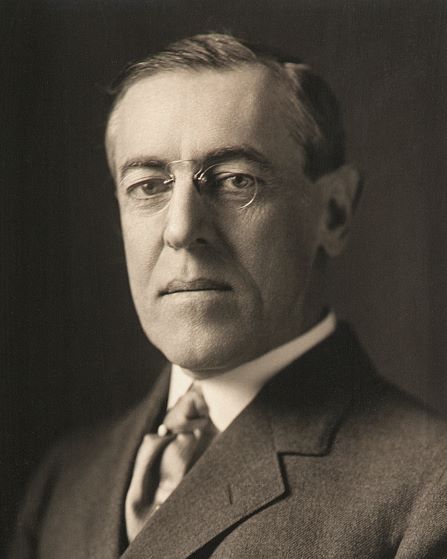

Across the pond, over in America, the studious scholar-teacher Woodrow Wilson of Princeton, already showing an occasional facial tic, suffered a fairly significant neurological episode in 1896—before the turn of the century. It left him with a weak right hand that forced him to write left-handed for about a year.

Then, in 1906, ten years later, he suffered another episode; this time he woke up blind in one eye one morning and weak in the right hand again. In time, the symptoms again did pass.

Still, he did become president of Princeton. He then, in 1910, changed career course and was elected governor of New Jersey, thanks in large part to the support of the state’s Democratic bosses. They would be surprised, however, when he stood up to them rather than kowtow to their interests.

Bully for him, of course, but Wilson hadn’t even completed one term as governor when the national Democrats turned to him in 1912 as a sacrificial candidate for president in the face of an expected political juggernaut in the form of the incumbent president, Republican William Howard Taft.

Except that fellow Republican Teddy Roosevelt, president just before Taft, spoiled all such expectations on either side by jumping into the fray on behalf of the Bull Moose Party, whatever that was.

Handed a three-way race, the onetime dark horse Wilson of course won the 1912 presidential contest and became President of the United States just in time to serve–even to win re-election in 1916—for the entire duration of the Great War.

With his background of neurological—that is, stroke-like—episodes, was he healthy, fit, enough to serve as president at any time in our history, much less at a moment when the world was at war?

One does have to ask when, in addition, his wife Ellen would die in the White House. When he constantly would be pressured to get in the war or to stay out of the war. When Germany and her allies would pay little attention to his edicts, when the passenger liner Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat in the spring of 1915 with Americans killed in the process. When his new love, Edith Galt, was temporarily stalling in response to his marriage proposals.

Let’s look more closely at that same spring of 1915, a time when the war in Europe has been underway for nearly a year, and add another hard-pressed national leader, British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith.

Middle-aged and married for a second time, war or no war, he was caught up in a hopeless romance with a young woman, Venetia Stanley, 28,his own daughter’s age.

For months, he had been sending her love notes reporting the most intimate secrets—not theirs, but of the British War Cabinet. So detailed were these love notes that, in the absence of minutes kept of those secret Cabinet meetings, they have become prime sources for historians of the period.

Since they outlined in detail many military decisions planned by the War Cabinet, just think what the German enemy could have done with Asquith’s love notes to a civilian…and by spring of 1915, his pleadings for her love in return! As capricious chance would have it, Asquith’s lady friend picked that same time of a British ammunition shortage on the Western Front and the disastrous Gallipoli campaign to announce she would marry a fairly young Asquith political protégé.

It was an understandably grumpy Asquith who now ejected the brash young Royal Navy chief, Winston Churchill, from the War Cabinet for his role in suggesting the Gallipoli gambit in the first place.

The same irrepressible Churchill then spent time in the trenches of the Western Front as an Army officer before bouncing back under David Lloyd George, the new PM, as minister of munitions.

Despite its staggering death toll, meanwhile, the Great War just went on and on anyway, a deadly proving ground for so many new weapons, such as the tank (promoted by Churchill), the airplane (another Churchill favorite), vastly improved artillery and that fearsome weapon of mass destruction, the machine gun.

As the very end approached, people in high places knew an armistice was in the works, the rumors flew, but, as bitter and avoidable irony, young men still were sent out to fight, to kill each other until, finally, that llth hour of the llth day, in the llth month of the year 1918, the Armistice and cease fire finally came.

Just before the magic hour did come, America’s ace aviator Eddie Rickenbacker took to the air and flew over the trench lines that made up the long-stalemated Western Front.

At 11 o’clock, he later wrote: “I was the only audience for the greatest show ever presented. On both sides of no-mans-land, the trenches emptied. Brown uniformed men poured out of the American trenches, gray-green uniforms out of the German. After four years of slaughter and hatred they not only were hugging each other, but kissing each other on both cheeks as well. I turned my ship toward the field. The war was over.”

So it ended, and yet even today, 100 years later, many serious people still are seriously asking how or why did it ever start? Who were those crazy people? As the well known British historian A. J. P. Taylor once said, “In July 1914 things went wrong. The only safe explanation is that things happen because things happen.”

Well, more precisely, people happen. One hundred and a few years ago, a madness of some kind possessed the people of Europe, especially their leaders—Churchill said it himself, “a wave of madness.” And eventually, in 1917, that same wave dragged our country into the Great War as well.

Thing is, you just have to wonder if and when these same sort of people may show up again. Perhaps even in our time. Or our children’s, and their children’s…after all, it did happen again in 1939-1941, with quite a few outbreaks seen here and there ever since.

- Guastavino Tile at the University of Virginia

- Abraham Lincoln on Character, Leadership and Education

- Silence is Golden: Celebrating the History of Silent Films

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Women's ACC Basketball Tournament - UVA Fan Events

- UVA Northern Virginia Programs Fair

- UVA Club of Los Angeles: Influential Communication