Loving Her Fiercely–Remembering a Playwright, Poet, and Author

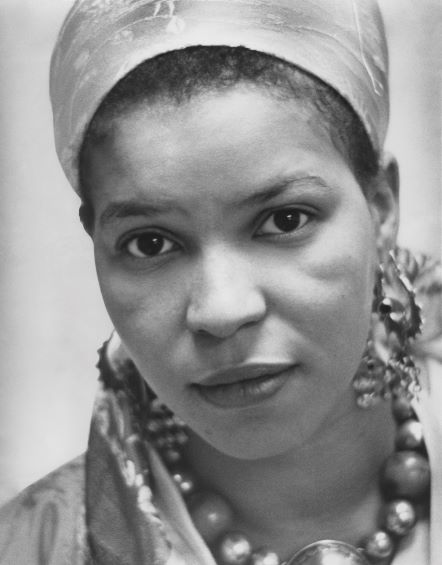

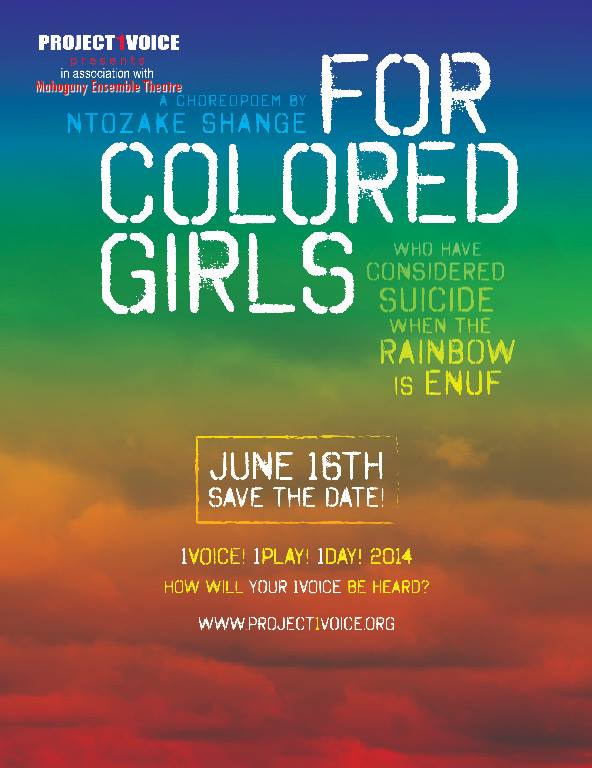

Playwright, poet and author Ntozake Shange, whose acclaimed 1975 theater piece, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, died on October 28th. Deborah McDowell takes a look at Shange’s influence on the arts and on black women seeking strength and affirmation. Ms. McDowell is the Alice Griffin Professor of English and Director, Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies in the College & Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia.

Playwright, poet and author Ntozake Shange, whose acclaimed 1975 theater piece, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, died on October 28th. Deborah McDowell takes a look at Shange’s influence on the arts and on black women seeking strength and affirmation. Ms. McDowell is the Alice Griffin Professor of English and Director, Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies in the College & Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia.

There are those lines from literature—or lyrics from song—that shake you down to your very core, that hit you where you live even though you didn’t know that “where” was a dwelling place inside of you. Those resonant closing lines of Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf are a powerful example of what I mean: “I found God in myself and I loved her fiercely.” Fiercely. The idea that God could be a “her” who lived inside a black woman, not “out there” or “up there,” was a radical, even blasphemous concept, particularly given my upbringing in a religious household in the segregated south of the 1950s and ‘60s. There, gracing the mantle of our living room, was the only image of “God” I had ever known: an 8 x 10, white-faced, longhaired Jesus in a gilt frame purchased from McClellan’s 5 & 10 Cents Store.

When Shange took the New York theater world by storm in 1976 with her choreopoem—itself a radical, generic concept—I was midway through a doctoral program at a Big Ten Midwestern university. The piece, which I saw performed there, was a kind of lifeline for me and for other black women navigating the treacherous waters of academia at a moment when we were only token members of the entire university’s graduate cohort. Writings by black women—no matter the field—did not appear on our course syllabi, and the “gods” of my graduate department openly discouraged my suggestion that novels by three African American women of the Harlem Renaissance might constitute the focus of my dissertation. I eventually prevailed and “the rest,” as they say, “is history.”

This was no easy victory, if victory it can be called, but it was made far easier by the fact that Shange and Michelle Wallace and Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker—and many, many others—had demanded through the force of their work that the world take notice, even if such notice was often grudging. The success of Shange’s choreopoem, along with that of other black women throughout the arts, was not uniformly celebrated. Indeed, their work was roundly condemned in many quarters, notably among black men with public platforms as journalists and reviewers, who accused black women writers, most especially, of plundering from the playbook of white supremacy by allegedly caricaturing black men as violent rapists, murderers, irresponsible fathers, domestic abusers, and general ne’er-do-wells. We, who had found a lifeline in this work, then and now, knew firsthand the truth of Shange’s telling, and were affirmed and consoled by those closing lines.

This was no easy victory, if victory it can be called, but it was made far easier by the fact that Shange and Michelle Wallace and Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker—and many, many others—had demanded through the force of their work that the world take notice, even if such notice was often grudging. The success of Shange’s choreopoem, along with that of other black women throughout the arts, was not uniformly celebrated. Indeed, their work was roundly condemned in many quarters, notably among black men with public platforms as journalists and reviewers, who accused black women writers, most especially, of plundering from the playbook of white supremacy by allegedly caricaturing black men as violent rapists, murderers, irresponsible fathers, domestic abusers, and general ne’er-do-wells. We, who had found a lifeline in this work, then and now, knew firsthand the truth of Shange’s telling, and were affirmed and consoled by those closing lines.

Whatever the hidden, gut-wrenching truths and wounds about black life and love the play had exposed in its most searing scenes, it gestures toward a place of healing at its climax, complete with a laying on of hands. Those closing words—“I found God in myself”—were both ointment and invitation, ultimately requiring some action on our parts. We could not receive the grace they promised secondhand, for implied in “finding” is “seeking.” In other words, the only God we can hope to find is the God we seek, even if that search lands us right back to the place from which we cannot flee for long: ourselves. Once we get “there,” we must claim, affirm, protect that god within, and love her fiercely, fiercely. The late poet and novelist, Michelle Cliff, was right: “Shange’s statement conveys a Black woman loving God, a Blackwoman-loving God, a Black woman-loving God—a Black woman loving herself fiercely—fiercely on her own account, finding herself worthy and divine.” Shange knew all too well that this newfound divinity would need to be our refuge, our ever-present strength in times of trouble, and against the ritual slings and arrows of the world.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of Charlottesville: ACC Football Championship Game Watch