Between the Right and a Hard Place: How JFK Pivoted to Righteousness

Written by Barbara Perry, White Burkett Miller Center Professor of Ethics and Institutions and Presidential Studies Director at UVA’s Miller Center. Follow her on Twitter @BarbaraPerryUVA.

Written by Barbara Perry, White Burkett Miller Center Professor of Ethics and Institutions and Presidential Studies Director at UVA’s Miller Center. Follow her on Twitter @BarbaraPerryUVA.

We don’t typically think of John F. Kennedy and Donald J. Trump as leading comparable presidencies. Yet they both faced a right-wing faction of their party over the issue of race.

In JFK’s case, southern segregationists represented a segment of the Democratic Party that Kennedy had to contend with in Congress, in Dixie’s governorships and flagship universities, and in the streets of the former Confederacy. Adding to the political complexity was their crucial role in his winning the 1960 electoral vote over Richard Nixon.

All of these factors forced JFK to walk a fine line between the Dixiecrats and the civil rights wing of his party, as well as civic leaders advocating racial equality. Martin Luther King, Jr. urged President Kennedy to declare the fight for civil rights a moral crusade and send a comprehensive bill to Congress to prevent discrimination in employment, education, and public facilities. Federal enforcement of voting rights also constituted a major goal of King’s movement. From 1961 to mid-1963, JFK refused to undertake both objectives, saying he would have more leverage once he won re-election in 1964. He worried that if he pressed for an expansion of civil rights, the balance of his New Frontier agenda would languish on Capitol Hill, stymied by senior members of Congress who hailed from south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

For Trump, the Tea Party faction of the GOP spurred his candidacy, and his stunning victory in 2016 undoubtedly has emboldened white supremacists. He, too, is struggling to satisfy these key constituencies while the other side calls for him to condemn them and the violence the latter perpetrated last weekend in Charlottesville.

Like the 45th president, the 35th had to address white supremacist violence in the first year of his administration. In May 1961, when young white and black “Freedom Riders” boarded buses headed to the South, in order to support federal court rulings for the integration of interstate transportation, they were set upon by club-wielding thugs in Alabama, who fire-bombed one of the Greyhound buses. The president’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, tried to persuade the civil rights activists to truncate their provocative bus rides, but the president did not declare that the southern segregationists had a defensible position or that the Freedom Riders were to blame for the violence perpetrated against them.

In the summer of 1962 President Kennedy faced new mobs, this time in Oxford, Mississippi, as he attempted to execute federal court orders to allow James Meredith to integrate the state’s premier university. Like Eisenhower before him, JFK sent in federal troops to quell the segregationists’ violence, but not before two bystanders were shot and killed. UVA Miller Center tapes from the phone conversations between the president and Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett reveal that Kennedy was trying to find a solution that allowed him to perform his duty under the federal Constitution, while not needlessly provoking the recalcitrant Barnett, who had stirred town and gown into a racist fury. (https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/secret-white-house-tapes/conversation-ross-barnett-2) With the attorney general and his superb civil rights staff at the Justice Department working behind the scenes and on location in Oxford, Meredith finally entered Ole Miss.

JFK faced the same specter of right-wing violence the next summer after federal courts ordered the admission of two black students to the University of Alabama. George Wallace, another demagogic southern governor, stood in the door of a campus building and declared that he would defy the federal government. President Kennedy and his brother sent Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to confront Wallace, and they federalized the Alabama National Guard to keep the peace. Ultimately, the governor relented.

Still, the Kennedy administration had not placed its moral suasion behind a comprehensive effort to write nondiscrimination policy into federal law. The second desegregation fight in as many summers, and the violent police responses to peaceful protests by young blacks in southern cities, pushed JFK over the fine line he had been walking on civil rights for his entire political career.

On the night of June 11, 1963, President Kennedy took to the airwaves to deliver a historic televised address to the nation, and indeed the world, on his change of heart and policy. He pointedly asked white Americans the striking questions, “[W]ho among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in [an African American’s] place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?” Declaring that “[w]e are confronted primarily with a moral issue . . . as old as the Scriptures and . . . as clear as the American Constitution,” the president announced that he would send broad legislation to Congress banning discrimination in American public life.

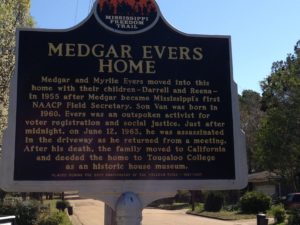

A few hours after JFK’s clarion call equating civil rights with the religious and secular symbols of Western civilization, a young NAACP field secretary in Mississippi, Medgar Evers, was brutally slain outside his home by a white-supremacist assassin. A few weeks later, President Kennedy met in the Oval Office with Evers’s widow, Myrlie, her two eldest children, and Medgar’s brother Charles. Before the year ended, the president himself would become the victim of political assassination and be laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery, near his fellow World War II veteran, Medgar Evers.

Just a little over one year after JFK’s belated but courageous move to equate racial equality with a moral imperative, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King each received a signing pen at the ceremony, but it was the late president’s leadership to move fully away from placating rightists and toward embracing righteousness that launched the most sweeping civil rights protections since the Civil War.

- A Revolution in the Air: The Wright Brothers Take to the Sky on December 17, 1903

- Musings on National Violin Day

- Making the Promise Real: How a UN Tax Convention Can Fulfill the UNDHR’s Vision

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Vietnam: J-Term Farewell Social

- UVA Club of Atlanta: UVA Women's Basketball at Georgia Tech