Trump and Kennedy at 100

Written by Barbara A. Perry, Miller Center Professor of Ethics and Institutions and the Presidential Studies Director at UVA’s Miller Center. She is the author of Jacqueline Kennedy: First Lady of the New Frontier and Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch. You can follow her on Twitter @BarbaraPerryUVA.

By historical coincidence, Donald Trump and John Kennedy are both the subjects of 100th anniversaries this spring. The incumbent president has just passed the 100-day metric for his new presidency, and on May 29th the country will commemorate the centennial of JFK’s birth. The 35th president would have become a centenarian this Memorial Day. It is hard for those of us with first-hand memories of him to contemplate that a century has elapsed since his birth. He is forever frozen in the public consciousness at a youthful 46, his age at the assassination in 1963.

This week the nation began its month-long tribute to President Kennedy with the premier of a biographical photo exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Gallery in Washington. It was a bi-partisan event, with Republican Senator John McCain recalling the inspiration his commander-in-chief, John F. Kennedy, imparted as the young Navy aviator spent an anxious several days aboard the USS Enterprise, steaming toward Cuba, during the 1962 Missile Crisis. McCain remembered that he hoped he could live up to the president’s faith in the courage of America’s military. He “was the very best man for the job,” the Arizona senator told the hundreds gathered in the Smithsonian gallery’s courtyard.

Historian Douglas Brinkley concluded the program with a reference to President Kennedy’s approval rating at the end of his first hundred days in the White House—an unprecedented and unequalled 83 percent. The crowd cheered, undoubtedly contrasting the number with the current incumbent’s equally unprecedented score of 40 percent in approval polls at the end of three months in office. The closest rating at the equivalent point in a presidency was Bill Clinton’s 55 percent after a rocky start as chief executive in 1993.

How could Kennedy have achieved such a rating, after winning the popular vote by less than a majority and only .2 percent ahead of rival Richard Nixon in November 1960? Moreover, JFK had stumbled badly in the April 1961 invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. Granted, Kennedy’s predecessor, President Dwight Eisenhower, had approved the mission to overthrow Fidel Castro, using CIA-trained Cuban freedom fighters. Who was Kennedy, a lieutenant (j.g.) in World War II’s Pacific Theater, to question the decision of the former Supreme Allied Commander and five-star Army general?

Kennedy made several crucial errors in moving forward with the plan—changing the location of the landing to the treacherous waters of the Bay of Pigs, not accounting for the swampland that surrounded it, mistakenly believing that the plan had remained secret, and not providing sufficient air cover for the invaders. Fiasco is the label most often applied to the failed effort. JFK accepted culpability in a press conference several days after the disaster. “I’m the responsible officer of the government,” the president observed. His approval rating spiked 9 points, from 74 percent, already a high level of public approbation as he had entered office in January.

By contrast, Trump arrived at the White House with the lowest approval rating (45 percent) since polling began in the Truman era. It dropped faster than any other president’s in the early days of an administration and reached a nadir of 35 percent last winter, a low to which some presidents, including Obama, never sank.

Why has Trump suffered such low polling marks and does it matter? How do his first hundred days compare to Kennedy’s? The two chief executives, whose career paths could not be more different, share intriguing traits and backgrounds. JFK’s father, Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., was a business mogul who founded a political dynasty, which at its apogee in 1963 included his three surviving sons as president (John), attorney general (Robert), and senator (Edward). Joe Kennedy was a skilled political strategist but an unsuccessful diplomat, and his aspiration to be America’s first Catholic president ended in 1940, when he averred that “democracy is finished in England” and might be in the U.S. as well. How times have changed. One injudicious comment derailed his nascent political career.

Trump is a business mogul who made it all the way to the Oval Office, despite (or perhaps because) of daily indiscretions. His populist message that he would upend Washington’s traditional power structure, to benefit Americans angry over a litany of perceived grievances, seemed more believable coming from a chronically indiscreet candidate. Like Joe Kennedy, Trump wants to install his children and their spouses in positions of power, and he is doing so with daughter Ivanka and son-in-law Jared Kushner now firmly ensconced in the West Wing.

JFK was America’s first TV celebrity president; Trump rose to the White House from the popularity of his reality show, The Apprentice. Kennedy mastered the new medium of television in debates and interviews; Trump’s tweets served as his social media route around traditional journalism and his direct link to the world. President Kennedy averaged two live, prime-time press conferences per month, while Trump tweets several times a day. JFK, briefly a journalist after his heroic wartime Navy service, enjoyed the company of reporters and counted many of them, like Newsweek editor Ben Bradlee, among his friends. Trump, however, has labeled media “the enemy of the American people,” a step beyond President Nixon’s characterization of journalists as his personal enemies.

Kennedy accepted responsibility for his public actions, even when they failed. “I don’t stand by anything,” Trump recently told CBS correspondent and UVA alumnus John Dickerson, in an Oval Office interview, abruptly truncated by a truculent Trump. And the president’s pattern is to blame his predecessor for all problems that land at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. It is clear from opinion polls that not accepting responsibility for anything is a problematic strategy. Or is it? Trump rarely topped 40 percent in pre-election polls, yet he won 46 percent of the popular vote – just by enough in four key states to garner a determinative majority of electoral votes. Like JFK, he is an incorrigible womanizer; but Trump’s vulgar behavior toward women, caught on tape, did not derail his candidacy. Nevertheless, polls reveal that popular trust in his honesty is plummeting. His inability to close a deal with his party’s congressional conservatives on repealing the Affordable Care Act in February, among his top priorities, prompted a firestorm of criticism. He could take pride, though, in the relatively easy confirmation of his nominee Neil Gorsuch to the U.S. Supreme Court. His criticism of the federal judiciary over its enjoinments of his travel bans, however, is inappropriate.

Trump has plenty of time to get the job right. As Kennedy himself declared at the end of his historic inaugural address, “All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days. Nor in the life of this administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.” Barring a premature end to the Trump presidency, he has at least three and a half years to “make America great again.”

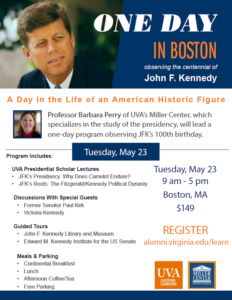

Barbara Perry will be in Boston on May 22 for a free reception and lecture on JFK and on May 23 for a UVA Lifetime Learning full-day seminar on President Kennedy at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. To find more information on these two events and to register, see the Lifetime Learning website.

Barbara Perry will be in Boston on May 22 for a free reception and lecture on JFK and on May 23 for a UVA Lifetime Learning full-day seminar on President Kennedy at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. To find more information on these two events and to register, see the Lifetime Learning website.

- Having a Drink With Your Donkey: The Absurd in Antiquity

- What Happens to UVA’s Recycling? A Behind the Scenes Look at Recycling, Composting, and Reuse on Grounds

- Finding Your Center: Using Values Clarification to Navigate Stress

- UVA Club of Atlanta: Virtual Pilates Class

- UVA Club of Fairfield/Westchester: Cavs Care - Food Pantry Donation Drive

- UVA Club of the Triangle: Hoo-liday Party